“If Shakespeare were alive today,” figures director Alex Timbers, “it’s more likely that he would be writing musicals than plays.”

It’s not hard to see why Timbers might think that, given how he’s been spending his time of late. Timbers has put his stamp on two Bard-inspired shows—as the book writer and director of Love’s Labour’s Lost, with music by Michael Friedman, which recently played in New York’s Central Park under the auspices of the Public Theater; and as director of The Last Goodbye, adapted by Michael Kimmel from Romeo and Juliet and featuring music by the late Jeff Buckley, currently running at the Old Globe in San Diego through Nov. 3.

Timbers isn’t the only one. Though the Bard is almost 400 years dead, a growing number of writers and composers are taking it upon themselves to set his work to music, and they’re not just doing it because his canon is in the public domain. (Although that technicality doesn’t hurt.)

One can argue that at its core, Elizabethan theatre is inherently musical—soliloquies and sonnets become songs, while verse is effortlessly translated into lyrics. Add to that Shakespeare’s impassioned, lovesick characters and epic plots and you have the ready makings of a musical drama or comedy.

“The need to reach toward verse and the need to reach toward song in a musical are virtually identical impulses,” argues director Aaron Posner, whose adaptation of The Tempest, with music by Tom Waits and magic by Teller, will play at Massachusetts’s American Repertory Theater in May 2014. The idea of the Shakespeare musical is nothing new, of course. Shakespeare himself wrote songs and used musical references in many of his plays. The most familiar modern adaptations are probably Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart’s The Boys from Syracuse (1938); Cole Porter’s Kiss Me, Kate (1948); Leonard Bernstein, Arthur Laurents and Stephen Sondheim’s West Side Story (1957); and John Guare, Galt MacDermot and Mel Shapiro’s Two Gentleman of Verona (1971).

When the Public’s artistic director Oskar Eustis began speaking with Timbers about working on a show for Shakespeare in the Park, Timbers says his mind immediately went to that 1971 Two Gents, which played in Central Park before it went on to win the Tony for best musical on Broadway. Teaming up with his Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson collaborator Friedman, Timbers set out to develop a pop musical of the lesser-known Shakespearean comedy, about three young men who take an oath to study for three years without the company of women.

Timbers and Friedman chose a contemporary setting for the play—a five-year college reunion—but maintained much of the original Shakespearean verse. Friedman calls it a “language-drunk show,” though that doesn’t mean the writing always went smoothly. “Iambic pentameter is famously horrible to set to pop music,” jokes Friedman, who used Berowne’s monologue almost in its entirety for the show’s climactic song, “Are You a Man?”

“It’s so much a play about language,” Friedman continues. “Even more than most Shakespeare plays—there’s performance, showing off, writing love letters, writing poetry. It’s full of sort of perfect break-out-and-sing moments, which not all plays offer you.”

There are a variety of ways, however, to make a musical based on Shakespeare. You can keep the verse and add contemporary songs, as in Love’s Labour’s Lost. Or you can make use of a well-known songwriter’s canon, as in The Last Goodbye or in Posner’s upcoming Tempest. Or you can do an aggressive rewrite, as was the case in the classics West Side Story and Kiss Me, Kate. Hip-hop has also been a popular approach lately, particularly for new interpretations of Othello.

In May, the Public presented a lab production of Venice, a hip-hop musical loosely inspired by the Moor’s tragedy, with music by Matt Sax and book by Eric Rosen. The show had its premiere at Kansas City Repertory Theatre in 2010 and a subsequent production at Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles, with Rosen at the helm. The director notes that Shakespeare’s different writing styles—from free verse to iambic pentameter—mirror different aspects of hip-hop.

“There are 30 different ways a Shakespearean character can talk. Hip-hop as a form is similarly flexible,” Rosen proffers. All of the music in Venice isn’t hip-hop per se, but the mélange of melodies and beats gives distinctive voices to various characters. Sax and Rosen’s earlier collaboration Clay—a one-man musical inspired by the Hal/Falstaff relationship in Henry IV, first produced in 2006 by Chicago’s About Face Theatre and Lookingglass Theatre Company and widely toured—taught Sax volumes about adapting Shakespeare. “I played nine different characters in Clay,” says Sax, who also starred in Venice as the Clown. “The question with Venice was: Can different characters speak differently, and how can you create musical themes that start in one character’s voice and resonate in the voices of others?”

Venice is set in a post-apocalyptic universe, and Sax and Rosen also drew from current events like President Obama’s election and the Arab Spring. “If you watch Venice thinking you’re seeingOthello, you would figure we don’t know very much about Othello,” Rosen acknowledges. “But if you know the heart of Othello, and compare it to the heart of Venice, you see that they share a lot of DNA.”

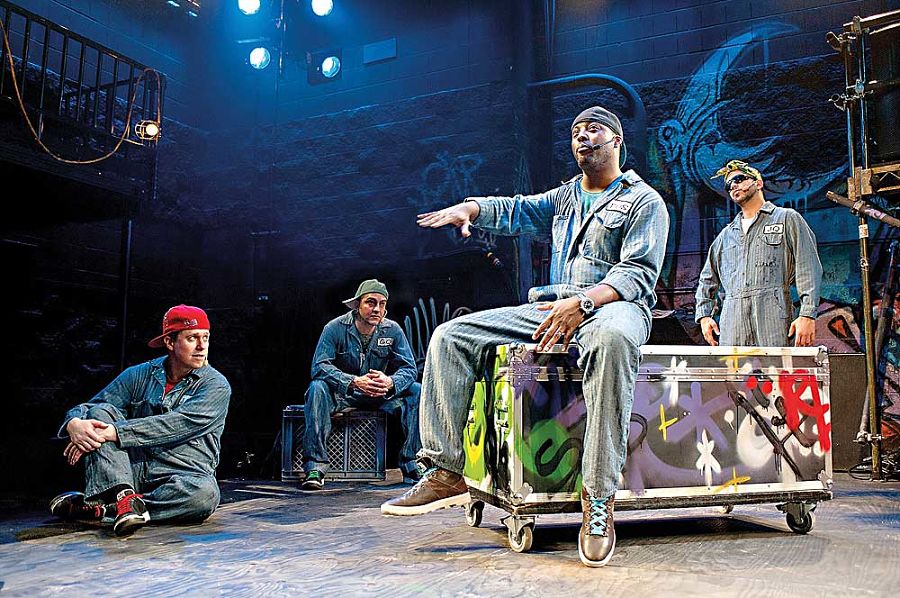

Chicago siblings the Q Brothers took their hip-hop musical Othello: The Remix in a completely different direction, as the entire show is set to rap rhythms. The show originated at London’s Globe Theatre in 2012, when the brothers were invited to perform as part of the Cultural Olympiad. The Globe presented all 37 Shakespeare plays in 37 different languages, and since Britain already claimed English, the theatre deemed American hip-hop a language of its own. After an acclaimed run ofOthello: The Remix at Chicago Shakespeare Theater ended in August, the brothers took it back to London in September for a run at the Unicorn Theatre.

“Shakespeare is a master storyteller who used musical-like poetry to tell his stories,” notes GQ, “and the best rappers in the world are also master storytellers who use musical-like language and poetry to tell their stories. There’s no question if Shakespeare were alive today, he’d be a rapper, because that’s his form.”

Adapting a Shakespeare tragedy was a new challenge for the Q Brothers, whose earlier works in this vein—The Bomb-itty of Errors (based on Comedy of Errors) and Funk It Up About Nothin’ (Much Ado About Nothing)—are comedies. Darker hip-hop artists like Dr. Dre and Eminem were their inspiration for musical style, but their initial translation felt heavy-handed and melodramatic. “We basically injected a lot more comedy than was in the original Othello, obviously.”

Timbers and Kimmel used the opposite strategy for their musicalization of Romeo and Juliet, which retains its entirely Elizabethan setting. The show had its premiere, directed by Kimmel, at Massachusetts’s Williamstown Theatre Festival in 2010, where it broke box-office records, but when Timbers came on board to direct at the Old Globe, he wanted to strip the show down to its essence. Timbers points out that Jeff Buckley didn’t write funny songs, and there is no comic subplot in the play, so the two are a perfect marriage.

“I really wanted to present a Romeo and Juliet that felt true, and exists in a society that understands this inexorable drive toward tragedy. To me, the high-concept thing about this piece is the Jeff Buckley music—what’s new and exciting about it is the addition of Buckley’s songs, as opposed to doing a musical version of the play.”

Posner has a similar approach to The Tempest. His adaptation is not an outright musical, where songs drive the story forward, but instead the Tom Waits tunes—both pre-existing songs and some new ones written for the show—open up the action. “If put together in the right way, narrative contemporary music and Shakespearean language can create a really energetic juxtaposition,” Posner ventures.

The only previous Bard-inspired musical Posner has done is Melissa Arctic, an adaptation of The Winter’s Tale with music by Craig Wright, which premiered at the Folger Theatre in D.C. in 2004. He cites Play On!, an adaptation by Sheldon Epps of Twelfth Night with music by Duke Ellington, as an inspiration for the new Tempest. Posner has set his production in the world of a traveling tent-show magician, and the tent becomes a metaphor for Prospero’s island. Waits’s iconic Americana, what Posner calls his Dust Bowl aesthetic, fits the concept perfectly. “This show will not only use the music of Waits, but the Waits vocabulary,” Posner adds.

production of “Othello: The Remix” in 2013. (Photo by Michael Brosilow)

Some writers use the musical form to fix what they see as structural problems in Shakespeare’s lesser-done plays. “People laugh when you say Shakespeare has flaws—but yes, there’s a reason that some of his plays are not done as often as others,” says David Rice, executive director of Chicago’s First Folio Theatre, where his folk-musical adaptation of Cymbeline, with music co-written by Michael Keefe, went up in June. The theatre has been producing Shakespeare for 16 years, and Rice has always wanted to do Cymbeline. But too much exposition and a convoluted plot prevented him from finding the right way to approach it.

“Summarizing some of that information in the form of a song allowed us to skip pages and get on with the plot,” says Rice, who set the show in Civil War Appalachia, with folk, gospel and bluegrass music.

Playwright Rolin Jones also thought a musical would be a great way to fix some of the plot issues in Much Ado About Nothing—like the play’s opening, where, Jones says, the characters are “lollygagging on an estate.” To put some external pressure on the action, Jones looked to the Beatles. In These Paper Bullets, Jones’s reimagining of the comedy inspired by Beatles mythology, the leads become the four Quartos—Ben, Claude, Balth and Pedro—and the plot imperative is that the band must cut an album in seven days (a reference to the Beatles’ early albums, which Jones explains were recorded in short amounts of time). Jones is teaming up on the project with Billie Joe Armstrong of Green Day, with whom he’s also writing the American Idiot film. These Paper Bullets will premiere at Yale Repertory Theatre in Connecticut in 2014.

Jones’s initial inspiration came from an unlikely source—the Kenneth Branagh film version of Much Ado, which opens with the men arriving home from war and everyone on the estate quite literally losing their minds. “It reminded me of all those people screaming for the Beatles,” Jones says. “This is a play of great passions. Everyone is in some heightened state—they throw caution to the wind, and that seems a lot like what rock-and-roll is supposed to be about.”

Jones calls his show an “aggressive translation” and a “bit of a mash-up” between the Bard and the Fab Four. “We’re not setting Shakespeare’s words to music, but his intention and a lot of his metaphors will be reflected in these songs,” he adds.

And the Shakespeare musicals keep on coming. Under the Greenwood Tree, a one-act musical reimagining of As You Like It, played at New York City’s Flea Theater in August; Peter Mills and Cara Reichel’s Illyria, based on Twelfth Night, which premiered at Prospect Theater Company in New York in 2002, got a new staging at Seattle’s Taproot Theatre in July; Old Sound Room, a new theatre company comprised of graduates of the Yale School of Drama, presented Old Sound Room Lear, a reworking of King Lear, in New York in June; and Amanda Dehnert’s The Verona Project, another derivation of Two Gents, is in development at California’s South Coast Repertory, where its run was postponed this spring (after stagings at California Shakespeare Festival in 2011 and the American Music Theatre Project at Northwestern University in 2012). “Shakespeare is great enough to survive all sorts of transformations,” asserts composer Friedman. “He can survive being cut. He can survive being set in different times. He can survive being turned into operas. And, actually, he exists in the culture partly because of all these other versions.”

Suzy Evans is a senior editor at Backstage.