Each month, American Theatre goes behind the scenes of the design process of one particular production, getting into the heads of the creative team.

Aficionados of August Wilson’s 10-play Century Cycle will know that the city of Pittsburgh is a prominent character unto itself. The creative team of the Goodman’s revival of Two Trains Running wanted to give the coal-dusted steel city of 1969 its full visual due. In this version, Memphis Lee’s diner, on the verge of being torn down in the name of urban renewal, is clearly seen as a refuge from a city that’s grown increasingly hostile to its African-American residents.

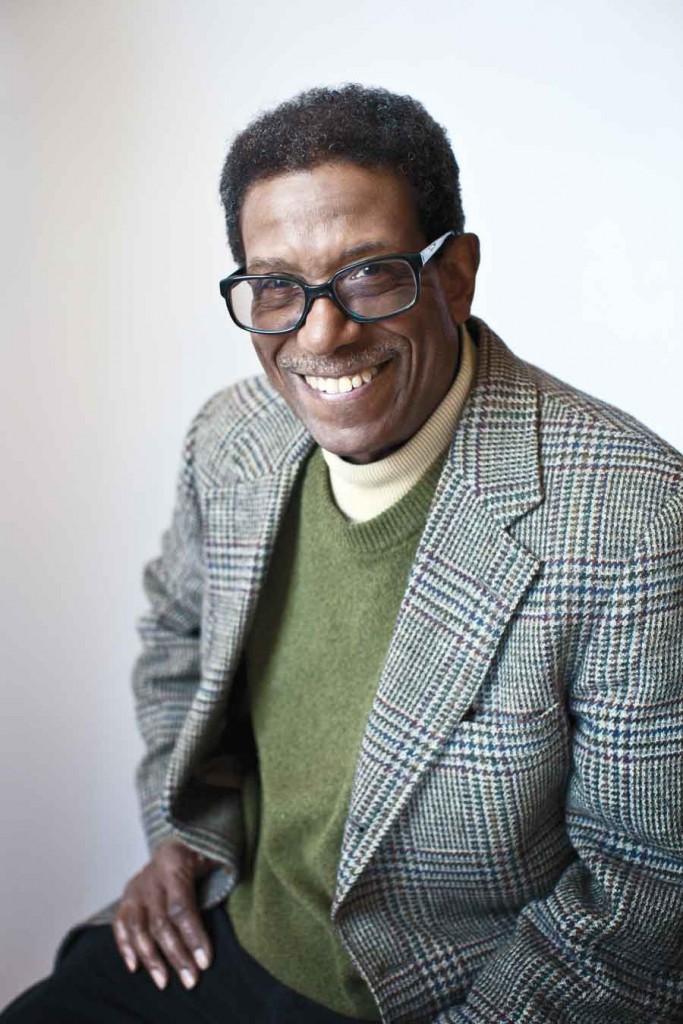

Chuck Smith, DIRECTION: What we had to show was a community in downward flux. So we had to show an area that was being torn down, but we also had to show a business. Memphis is making ends meet, barely. That had to be shown. And we had to show a place where people would actually want to be. The key was the diner had to be decent, and outside had to show some sense of ruin—that something’s going on outside that’s not good.

I had directed Two Trains Running once before, a college production in 2007. Though it wasn’t ever on the top of my list of favorite August Wilson plays, I like it the best now. When done correctly, we see that it’s August Wilson at the very peak of his writing talent in terms of characterizations and storytelling. And these people have become my favorite people: Every one of them is someone I’d want to spend time with and sit down and talk to. And I want to spend more time in that diner!

There’s a moment in the play that has become one of my favorite moments in any play. In the second act, we see these two characters, Holloway and Wolf; they look at each other and they take a position looking out the window, and we see the light coming up on them. And Holloway starts talking. It’s such a beautiful little moment that was able to occur because of the lights and the set design.

Linda Buchanan, SET DESIGN: I feel a personal connection to this play because I grew up in Cleveland, and Pittsburgh was a few hours away. The year of the play was the year I was a senior in high school. So I know what Pittsburgh was like then, and the thing that always stuck with me was that it was so smoky from the steel mills and a lot of coal burning. So we wanted to capture that a little bit.

We also wanted to capture what was going on in that neighborhood at that time—the sense that the whole neighborhood is kind of dwindling away and falling apart in the face of impending “urban renewal.” Because of the economy, because of poverty, a lot of businesses have left. The buildings are just boarded up, a lot of things are being torn down, and a whole bunch of this neighborhood was razed in preparation for a big civic auditorium (which ironically got torn down in 2012). So that led us in the direction of the really realistic interior and a more abstracted, kind of a black-and-white color palette exterior.

I happened to come across in my café research a really beautiful abandoned diner. There was this really stunning blue-gray wall with the steel counter and backboard against it. There was something nostalgic about it; the blue to me feels a little more like a memory. And we warmed it up a little with the dark reds in the booths. It really let us focus on the actors more than a lighter and warmer color palette might.

August Wilson’s plays always move between the smaller-scale, realistic feeling of daily life, and the epic-scale poetic monologues. Often the epic part doesn’t have to be visually represented. It can be left to the actors to express. But we had the opportunity—the scale of the theatre space was big enough—that we could [represent it]. I thought there might be something interesting in seeing our characters come through this bleak landscape before they enter this room. We could see a little more of the lives of these people outside just from watching the way they enter, the way they approach the café.

Two Trains Running played at the Goodman Theatre March 7–April 19, under the direction of Chuck Smith. The production also featured set design by Linda Buchanan, costume design by Birgit Rattenborg Wise, lighting design by John Culbert, sound design by Ray Nardelli, dramaturgy by Neena Arndt, production stage management by Alden Vasquez, and stage management by Kathleen Petroziello.