One early avenue to the acting profession is the desire to be another person, a realization that generally occurs after watching others. It is a natural impulse and happens when you admire something so much that you want to imitate it. Through imitation, we acquire language, learn how to walk and recognize the world around us. That is why the most basic acting exercises are based on pretending to be something else—a prowling animal or a stationary clock, a growling lion or a whirring hair dryer.

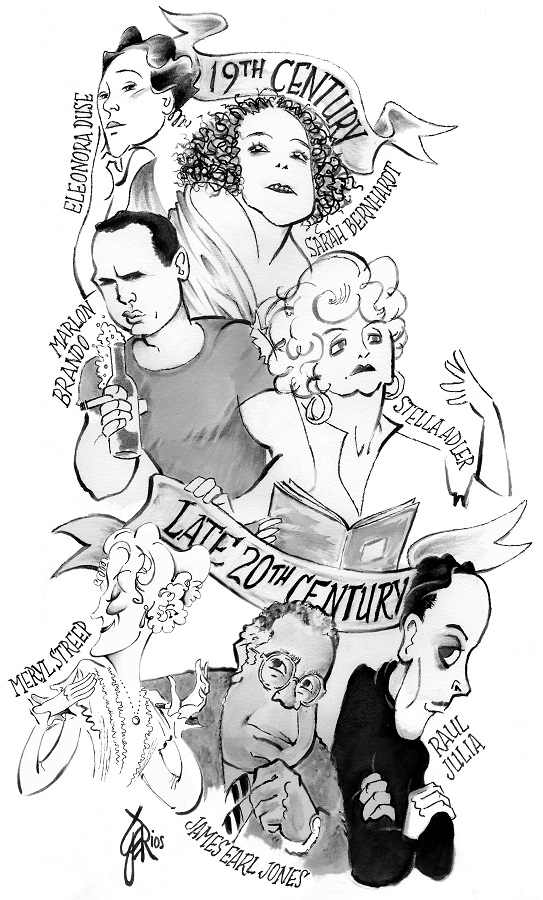

Most actors born in the 20th century first learned to imitate movie stars. But for centuries before that, young people were attracted to a theatre career because they worshipped the stage idols of the day—Richard Burbage and Will Kempe in Shakespeare’s time; David Garrick and Mrs. Siddons in the 18th century; Edmund Kean and Edwin Booth in the first half of the 19th century; Eleanora Duse and Sarah Bernhardt in the late 19th century; John Barrymore and the Lunts in the early 20th.

Barrymore, for example, with his aquiline profile and emphatic snort, initiated a whole cottage industry of heroic acting in the 1920s and 1930s (Fredric March, Ian Keith and John Carradine all owed him something), especially after triumphing as Hamlet on Broadway and in the West End. As a young actor, my idols were Laurence Olivier and Robert Newton, especially after I saw them respectively as Henry Plantagenet and Ancient Pistol in the 1944 English movie version of Henry V. It was the first time I realized that Shakespearean verse, rather than simply being words designed for rote memorization in high school English classes, came out of the mouths of real people. Every role I performed for a decade after would be flavored either with the clipped nasality of Olivier or the flamboyant eye-popping of Newton, until I then discovered that although imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, it is the least original form of acting.

After Marlon Brando broke into the American consciousness as Stanley Kowalski in both the stage and movie versions of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, virtually every male wannabe actor in America was mumbling his vowels, seething with proletarian rage, glowering and walking around town, regardless of the weather, in torn T-shirts. You can see Brando’s influence on Paul Newman, Steve McQueen, Jack Nicholson, Robert DeNiro, James Dean and Ben Gazzara; and even on young actors such as Joaquin Phoenix, Sam Rockwell and Josh Hartnett today.

Hamlet calls actors “the abstracts and brief chronicles of the time,” a phrase that perfectly captures their capacity to embody and reflect the style of an entire period. Some actors even have the potential to change the style of an entire period; this was quintessentially true not only of the young Brando, but also of the young James Dean, and today, to a lesser extent, of Tom Cruise, Sean Penn and Johnny Depp. When Christopher Walken played Caligula at Yale in the early 1970s, scores of undergraduates in New Haven began imitating his loping walk, his eccentric speech, even the clothes he wore.

While widely copied, performers have always been considered unconventional in style and moral behavior. They can mesmerize adoring audiences while scandalizing politicians and moralists, not to mention their mothers and fathers. Remember the outrage that greeted Janet Jackson when she exhibited her breast at a football game on national television? Think of it! Exposing little children to such profanation—as if an exposed female breast were not the very first object a newborn sees. But this ability to concurrently draw down admiration and dismay is central to the performer’s appeal.

“Don’t put your daughter on the stage, Mrs. Worthington,” Noel Coward writes in a well-known musical admonition. I would guess that many of you have experienced some of the parental disapproval suggested in that satiric lyric, even though social resistance to a theatrical career has diminished somewhat during the past 50 years. Economics are still part of the problem. An actor’s career is a crapshoot, and the odds are long that you will turn up a seven or an eleven on the very first throw. Parents have feared their children will be dependent on them beyond their teenage years, and few consider life in the theatre to be either a good investment or moral choice.

Actors don’t keep the same schedules as normal people. They sleep late and stay up late, turn night into day and day into night. Although they work extremely hard when they are employed, they are often out of work, and a Puritan society considers idleness the devil’s stepchild. Even in an age of relative sexual permissiveness, actors, women in particular, are still considered promiscuous, attitudes that stem from the days when the only females allowed on stage were orange girls and prostitutes.

Based on the behavior of a handful of habitual users, actors are also considered notorious addicts. John Barrymore made a career out of his weakness for John Barleycorn. So did W. C. Fields, who always carried a bottle of gin, disguised as a bottle of grapefruit juice, in his rucksack (inspiring his priceless remark, “Who put this grapefruit juice in my grapefruit juice?”). More recently, another epic boozer, Elaine Stritch, created a one-woman show about how she overcame her addiction to alcohol, and that splendid actor Robert Downey Jr. has been in and out of rehabilitation centers for years. And just as Barrymore, an incomparable Shakespearean on stage, was always best at playing alcoholics in the movies, so Stritch can be a terrific stage drunk (not so long ago in a Broadway revival of Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance); and Downey is unequalled in capturing the lonely despair of the hopeless cocaine addict (as he did in the movie Less Than Zero).

Because of their celebrity, actors are obliged to lead their private lives in public, and this is why the mistakes of the few are often seen as the misdeeds of the many. Still, there is probably some truth to the charge that actors are more likely to be less abstemious than ordinary mortals. When you’re coming off the tense excitement of a taxing performance, the last thing you want after the curtain falls is to drink a glass of water and go to bed. The local bar is the modern equivalent of the Mermaid Tavern, where Will Shakespeare and Richard Burbage often traded stories (and girlfriends) over a round of drinks. (That particular establishment was located on Clink Street, and its famous brawls could explain why the term clink became a synonym for the hoosegow). On the other hand, the more bibulous actors of my acquaintance often struggle valorously to control their habits, realizing, no doubt, that immoderate behavior will eventually affect their performances on stage. And the great majority of actors are as balanced and healthy as anybody in the audience.

This question of moderation, dear Actor, is also related to the issue of stamina. You need a lot of strength to survive the pressures of the profession, and you shouldn’t even consider acting unless you have the capacity to endure its heartaches and its disappointments. For a long time, I have been convinced that one of the most important criteria for theatrical success is the capacity to stay the course, no matter how discouraging things get. I have known actors loaded with talent who did not have the will to endure rejection and disillusionment; and I have known far less gifted actors who have succeeded as a result of pure stubbornness and pluck.

My observations suggest that those who are too sensitive often lose out to those blessed with bigger calluses on their souls. There is some truth to that. But don’t underestimate your capacities for overcoming adversity. Just as Chekhov was always exhorting his brother Alexander to get some iron in his blood, so I would advise you, dear Actor, if you’re truly serious about being a professional actor, not to drop out because your skin is too thin. Rather, try to stick to your central purpose and, in doing so, learn how to bear the rejections and rebuffs that come your way.

Your best model in literature is Nina in Chekhov’s The Sea Gull. Nina suffered poverty and disappointment and self-doubt, but she finally came to know that endurance is what counts:

In our kind of work, whether we’re actors or writers, the important thing is not fame or glory, not what I used to dream about, but learning how to endure. . . . If I have faith it doesn’t hurt so much, and when I think of my calling I’m no longer afraid of life.

Remember that speech, dear young Actor, for those words will see you through.

Chekhov’s Nina refers to her “calling” rather than to her “profession” or her “job.” What does she mean by this word? She has simply recognized that to be an actor is tantamount to becoming part of something larger than herself. We rarely use terms such as “calling” much any more; they sound suspiciously like the language employed by monks and nuns, of anchorites who mortify the flesh with scourges and hair shirts. In an age of celebrity, we are much more accustomed to seeing the fashion defer to individuals than to watching individuals subordinate themselves to a consuming purpose.

Yet, not many years ago, Ibsen was writing a lot of plays about the importance of a calling because he believed, as did Kierkegaard, that “he who forfeits his calling, forfeits his right to life.”

Indeed, the corpus of modern drama is remarkable for how many plays deal directly with the tension between the private individual and the public mission, between selfishness and the selfless calling. This may be why the actor has become such an iconic figure of our time. Nobody exemplifies more prominently this particular split in the human soul between inner-direction and other-direction; nobody represents better the wide range of options available to every human being.

And nobody is a more accurate reflection of a given time. The actor is like a mirror into which everyone desires to gaze. If you achieve a really phenomenal success, your performances will be carefully scrutinized on and off the stage or screen. Actors, especially star actors, now serve the same function for us as the Olympian gods served for the Ancient Greeks; and, like debased versions of Homer, gossip columnists and tabloids record the myths of the powerful and legendary. Zeus’s amorous escapades with Leda or with Alcmena, for example, have morphed into the imbroglios of Ben Affleck and Jennifer Lopez or into accounts of Madonna’s various affairs and religious conversions; and in the same manner, Mary Astor’s diaries once exposed to the world her various dalliances with actors and writers. Marriages, divorces, adulteries, births, and deaths involving Hollywood celebrities receive the same banner headlines as wars, revolutions, earthquakes and famines. And if a star runs afoul of the law, as Robert Blake and Michael Jackson have, then the journalistic heavens open and pour down black rain.

This burden is a lot for one person to handle, and many an actor has wilted under the strain. The late great Marlon Brando, who had grown so elephantine that he could only be photographed if he was obscured in shadows and half light, was clearly someone whose distaste for his own celebrity had resulted in a pathological eating problem. This disorder was no doubt linked to his cavalier attitude towards acting. He famously refused to memorize his lines, preferring to take long pauses while his eyes wandered lazily towards the cue cards. He talked about his profession as if it were a mug’s game (his autobiography, Songs My Mother Taught Me, would have been better titled Why I Hate Acting). Instead of graciously accepting the Academy Award he won for The Godfather, for example, he sent a Native American to the podium to reject the Oscar statuette in protest against Hollywood’s failure to treat Indians with respect. Richard Gere accepted his Academy Award on behalf of the Dalai Lama of Tibet. Others, glancing towards heaven, thank dead parents or God, or those living surrogates for God and parents, their agents. Few manage to give the impression that the art of acting itself can be a significant source of gratitude and pride.

If you look at the way actors embrace their calling in England, you will see that something is seriously missing here in the American acting scene. It is true that respect for the actor is much higher in England than in America (and I am not counting our movie stars, who attract more idolization than respect). In England, one can become a knight or even, as Laurence Olivier did, a peer of the realm, after a lifetime of distinguished theatrical achievement. In our country, the highest public distinction an actor can receive is a presidential medal at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and that award is usually made on a condition of political loyalty to the current administration.

Still, even in England, actors can sometimes feel contempt for their profession. There is a poignant moment in John Osborne and Anthony Creighton’s Epitaph for George Dillon during which the title character remembers when he was in the Royal Air Force during World War II, and one of his mates asked him his profession:

“Actor,” I said. The moment I uttered that word, machine-gun fire and bombs [falling] all around us, the name of my calling, my whole reason for existence-it sounded so hopelessly trivial and unimportant, so divorced from living, and the real world, that all I could feel was shame.

This kind of shame is no doubt shared by many actors uncertain about their profession, and that may be a reason why some Academy Award winners like to make acceptance speeches about their social and political commitments rather just thank the Academy. Deep down, they must believe that acting is an art so “hopelessly trivial and unimportant,” or “so stupid, so ridiculous, so false” that it is divorced from the real world.

But as soon as an actor starts thinking of the profession as “the business,” then it is inevitable that he or she will be more preoccupied with material rewards than with artistic satisfactions. Most people don’t have that choice. Most professions are oriented either towards service or towards profit. In acting, the options are blurred. Many doctors, more interested in their stock investments than in the latest medical discoveries, may prefer studying Investors Weekly to reading Lancet. But their first obligation is still to heal their patients, or at least “to do no harm.” Priests, ministers and rabbis are sometimes worldly and ambitious, but their accountability is first to their God and their congregations. By contrast, some businessmen may be extremely philanthropic and some lawyers may do a lot of pro bono work, but they are in professions where the name of the game is profit. Actors are about the only ones who can choose between monk and plutocrat, maverick and mogul; who can go around in either sneakers and Levis or Armani suits and Tiffany jewelry.

So if one of the career options before you only to artistic fulfillment and spiritual satisfaction, another only to mass approval and material gain, you can hardly be blamed for choosing the latter. Everyone—your parents, your peers, your friends, your agent—will say you’re a fool not to take the highest-paying offer, even if that sometimes means what Shakespeare called “a waste of spirit in an expense of shame.”

The question remains not so much how you can pay your respects to God and Mammon both, but how you can pursue your career without losing dignity and self-respect. It is not going to be easy. In the unlikely event you do become a star, the public will believe it owns you. Your private life will become raw material for scandal magazines, your public outings meat for camcorders and digital cameras. You won’t be able to go to a rest room without being followed, and although that may please your vanity at first, it will soon become a torment. Every star takes his life in his hands the moment he ventures out in public to be greeted by “adoring” fans.

But in contrast with the incivility often displayed towards actors, there are also expressions of genuine gratitude for what they bring into people’s lives. Let me tell you what Stella Adler once wrote after seeing the YRT company perform Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida. First, she praised the cast “for their total sense of giving us all they had—all their richness and spirit.” She went on: “And by the time they lined up to bow, I understood there is no more noble man in the world than the actor.”

The nobility Stella Adler speaks about is not always evident in the sometimes tawdry world of the performer. The long rides by bus or train or plane; the sometimes dreary stopovers; the all-night restaurants and one-night cheap hotels; the peeling dressing rooms with their unemptied wastebaskets. Chekhov’s Nina speaks of these trials in The Sea Gull, and O’Neill’s James Tyrone’s relentless touring schedule is one of the reasons his wife, Mary, became a drug addict. On the other hand, there is no question that, at his or her best, the actor is the vessel through which we witness the most extraordinary things of which humans are capable, whether heroic or villainous. These qualities are often embodied in the characters they play—Orestes, Jocasta, Medea, Lear, Brutus, Iago, Macbeth, Hamlet, Coriolanus, Mirabel and Millamant, Willy Loman, Blanche Dubois—people who murder and create, marry and procreate, conquer and suffer, decline and fall, rise and transcend. That preeminently human quality is also evident in the courage the actor displays just by getting up on stage. Supported only by talent he bares the inner torments of the character, and, inevitably, something of the actor’s soul as well.

Many actors fear, however, that in assuming so many identities they may lose, or not even develop, one of their own. This is the dilemma of Luigi Pirandello’s actor-heroine in his play To Find Oneself (Trovarsi). Seeking her essential but elusive personality, she discovers that it lies not in her self but in her art, in the various roles she has played. An actor lives before a mirror and absorbs the numerous reflections being thrown back. The theatrical disguises Pirandello’s heroine assumes in front of an audience are what constitute her real identity. “It is true only that one must create oneself, create! And only then does one find oneself,” the play tells us. In short, the very act of creation becomes a noble act of rebellion against existence. Actors are superior precisely because they know they use disguises. They are not only the sum of their own actions, they are also the sum of the roles they play.

So do put your daughter on the stage, Mrs. Worthington. She may not always make a decent living there, but she will be part of an ancient and honorable mystery, and it is on the stage that she will most likely be able to find herself.

Robert Brustein serves on the faculty and as a founding director and consultant for American Repertory Theatre. He has been a playwright, director, actor, teacher and critic.

From the book ‘Letters to a Young Actor’ by Robert Brustein. Copyright © 2005. Reprinted by arrangement with Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Books Group. All rights reserved.