Ellen Orenstein is an associate professor of theatre arts (acting) at Marymount Manhattan College. Her writing has been published in TheatreForum and Theatre Journal. In Feb. ’08, she will assistant-direct “The Seagull” (featuring Dianne Wiest) at Classic Stage Company.

Over the course of the past year, I have had the unique opportunity of sitting down, my tape recorder in hand, and conducting a series of in-depth interviews with eight extraordinary teachers of acting. I was initially interested in simply recording each of their personal experiences with teaching, but what arose out of our time together was a topic more extensive and far-reaching: what it means to teach acting—to train American actors beyond technique.

The conversations revealed how these teachers, from vastly different backgrounds and professional experiences, have grappled with the struggles inherent in the teaching of any art form, and, most specifically, the teaching of an art form that relies on the student’s own sense of self and independence from the teacher as a necessary and significant skill. All eight speak of teaching students independence, the necessity for an emphasis on process and the importance of removing, ultimately, the authoritarian presence and power of “teacher,” thus allowing, helping, students to take control of their own work as actors.

The perspectives of these training professionals on both acting and the teaching of acting are inspirational for all of us who must face what it means to act and to teach, and who understand that acting is something that can, indeed, be learned and taught—in practical, useful and significantly substantial ways.

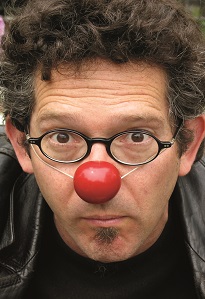

CHRISTOPHER BAYES

Yale School of Drama

Bayes is head of physical acting at Yale School of Drama in New Haven, Conn. He has served on the faculty of Brown University and the Brown University/Trinity Rep Consortium in Providence, R.I., as well as the Juilliard School, the Actor’s Center, the Academy of Classical Acting, and New York University’s Graduate Acting Program and Experimental Theater Wing. He has taught workshops at the Public Theater’s Shakespeare Lab, Cirque Du Soleil, Williamstown Theatre Festival and the Big Apple Circus. Bayes’s theatre career began in Minneapolis, where he worked for five years with Theatre de la Jeune Lune as an actor, director, composer, designer and artistic associate. In 1989 he joined the acting company of the Guthrie Theater under the leadership of Garland Wright, where he appeared in more than 20 productions over seven seasons. He has directed widely in New York and regionally.

It seems that an enormous part of your teaching is working with the performers to be connected to the audience—to become friends with the audience—but not to perform for the audience, for the laugh.

Actually, I think I try to train people to perform more for the audience. Not to try to solve the problem of the audience by manipulating it in some way, but to invite the audience into a deeply vigorous, playful comic world. So it’s not about where the laugh comes. It’s about how you live in a comic world without needing to solve the problem of the comic world.

Do you work in a horizontal plane in the classroom, rather than vertical, in terms of the authoritarian presence of the teacher?

No. (Laughs.) No, no. If I did it that way, then there would be more room for argument or resistance. I think it’s very important that you make it clear you have an opportunity to investigate something together, but that you’re going to have to, at a certain point, embrace the hierarchy of how that’s going to be investigated. It’s important that that relationship is established right away.

You go to the teacher because the teacher has something of value—but that something demands of the students to be open, to be ready. I don’t want to ever feel like I’m your dentist—that I’m pulling something from you that you’re reluctant to give. I’m trying to make more room in your body for your talent to surprise you.

Have you encountered students who are so enamored of what you’re doing that they stop working for themselves, or for the thing itself, and start working only for you?

Not really. I think the people who come to study this work are anxious enough about learning this training that that doesn’t happen as much. (Laughs.) Because I almost solely investigate the comic world, if the rest of the students don’t laugh, then it’s not funny. And I laugh when everyone else laughs, generally.

I’ve noticed, though, that you’re not overly effusive about your responses. Is that on purpose?

Well, my responses are usually, “Great. And now…” or, “Great. But…” Generally, when we go back and make those adjustments, then the room laughs more. It’s in the adjustment that you find those magical moments of transformation or insight. I have a very specific arc of training that I’ve developed over the years—and that’s pretty set.

Can you describe that?

Well, right out of the gate, I bring a kind of lightness to the room, a playfulness, that it’s not that precious. If the audience doesn’t laugh, it’s not the end of the world. It means you haven’t invited the audience properly yet. We always start with group songs—very simple ones, like “it’s so funny” or “I’m so funny.” The songs do everything that I think is exciting about theatre: There’s kinesthetic awareness, there’s harmonic listening, there’s some choreography involved, there’s playfulness and abandon in the solos, as well as a way to go back to structure.

And the instructions are…?

The song has to have four elements: It has to have a really strong chorus that you all sing together in the speed of fun, which is pretty fast; there’s choreography that everybody does; there’s harmony in the chorus; and everybody gets a solo. I encourage the actors to take the time to say what they need to say. And I discourage rhyming in the solos because I feel like unless you’re a genius, as soon as you begin to pursue a rhyme, you end up saying all kinds of ridiculous things that you don’t really mean in order to solve the problem of the rhyme. I try to discourage the solution. I want the students to enjoy the problem more. Once you can begin to enjoy the problem, then we don’t feel the dynamic that the actor would rather be off stage as quickly as possible.

This is appropriate for tragedy, also.

All the most beautiful actors enjoy the moments that they’re in the light. That’s why we do the work, right? Enjoy the challenge. Find pleasure in the fact that you are actually on stage in front of people, in a conversation with the audience—it’s not a lecture, or a demonstration of how brilliant you are, but actually conversation. The most basic and fundamental theatrical conversation, I think, is the conversation between the clown and the audience. It’s prehistoric. (Laughs.)

When you first meet the students you are going to work with, what do you see?

Almost everybody’s nervous. Including me. Because we’re about to jump off a big cliff together, and we don’t know what we’re going to find.

I begin with everyone the same way, which is that we are going to build up or reinvestigate certain muscles, impulses, that may not be very strong—may not have been given the value they deserve. A sense of innocence. Soft brain delight. A way of living in your body with a kind of squirrelly-ness. A lightness. But also, at the same time, a kind of muscular ferocity that allows you to give as much value to your playfulness as to your despair.

When I get to know the students more, I begin to see the catch places—the places where they are reluctant to go. If I see people reluctant to be messy, then I make them be messy. If I see them reluctant to be out of control and ferocious, then I make them—I encourage them to go there. If they’re reluctant to be quiet—to really listen to their own bodies in a quiet, delicate, fragile way—I ask them to do that, and I try to build a physical life that allows them to go there.

Also, you have to do battle with the socialized self. And the great desire to be polite, the great desire to be appropriate, the great desire to be cool, to be in control. The desire to not look stupid.

What happens when you get past that place?

Then you find the clown.

That’s when you begin to do an exploration of what the clown is, what your relationship to the audience is, what your relationship to your clown is. I always feel like the clown is the beginning of everything. That everything springs from that. That thousands of characters can come from the clown. But there’s one—and it’s you. It’s the one that got tucked under the bed in the shoebox.

And it’s the most exposed you.

The skinless grape. (Laughs.) The softened armor. But, with a kind of honesty—of incredible, vulnerable honesty.

It seems so connected to the most basic actor training—pure Stanislavsky, in a way.

But, it’s relatively new, actually, that it’s in training programs.

What I hear again and again from other teacher artists is that after students have done clown, all of a sudden they can listen—because they are curious about the answer—not because they already know what the answer is and now it’s time for them to respond.

The ultimate goal seems the same as with many other forms of training: pure authenticity and truth.

Right. Mine is just oriented toward the comic world. What’s interesting is often that moment of truth is where the laugh is. It’s not in the clever idea—it’s not in the good idea. It’s in that honest response—to the fact that there wasn’t the laugh there where you wanted one. We laugh because we understand. We laugh because it makes sense. Not because you’re clever. Not because you’ve manipulated us.

How does this work give ownership to the actor?

The actors are generally the last ones invited to the party. (Laughs.) They’ve already designed the costumes, they’ve already designed the set—you were cast to fit into a machine that’s already in the process of being built. But when you begin to explore the world of the clown, you see all that other stuff that we think of as necessary to make an interesting theatrical world—that becomes frosting. The actor is the central, creative element. And it’s incredibly empowering. You can take that into anything—into Shakespeare, into the Greeks, into Shaw or Pinter or, obviously, Beckett. You can go anyplace—because it’s yours. Clown, for me, is a rediscovery of self. The playful self. The ferocious self. The vulnerable self. The artist.

VALERIE CURTIS-NEWTON

University of Washington

Curtis-Newton is associate professor in acting and directing and head of directing at the University of Washington in Seattle. She is an artistic associate at ACT Theatre, where she oversees the Hansberry Project, an African-American theatre lab. She has directed projects and taken part in new-play development at professional companies nationwide. Previously she served as artistic director for the Performing Ensemble of Hartford and the Ethnic Cultural Theatre at the University of Washington, and was a recipient of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Foundation’s Sir John Gielgud Fellowship and a UW Presidential Faculty Development Fellowship.

You’re a very actor-friendly director and teacher. Can you talk about your unique way of working with actors?

Something I try to teach young actors and directors is that the obstacles in the rehearsal process are almost always based in a fear of something. When I’m talking with actors about a moment that isn’t working, I try to figure out what it is that is keeping the actor from fully attacking that moment.

Can you offer a specific example?

It may be that the character has to be really vicious in a moment. The actor’s impulse is, “I don’t want her to be a bitch,” or “I don’t want him to be a villain.” But if in the moment before, that character was hugging their kid, and now they’ve got a knife out—it doesn’t mean that character is a bitch. (Laughs.) They can trust the complexity of a character to reveal itself over the course of the play.

You also have to recognize that sometimes the character is in the play to be the villain. It is that character’s function. And if you undermine the strength and clarity of their pursuit of getting what they want—by trying to make the character magnanimous or altruistic—you undercut the play.

Can your actors hear that?

Almost always, when they’re confronted with the actual function of the role. I encourage them to remember that the character is something they play, something they do; it’s not something they are. I am constantly articulating where it is that the character wants to go in the end. So that the actors are aware of what their objective is in the moment—but there’s an echo of what that moment is in service of.

There is a negotiation between the power of the teacher or director and the self-reliance that has to be instilled in the actors. How has this shown up in your teaching and directing?

I think that’s how I began to evolve this question of finding the fear in the room. Is it a fear of my judgment? Is it a fear of the judgment of their peers? Is it the fear of the judgment of an audience? I remind them that the fear is present in every actor in the room, all the time, and that one can recognize it and continue to work without being distracted by it. I can reassure them that they can fail, and I will not think that they are any less talented.

And do they believe you when you say that?

Well—over time. (Laughs.) Invariably, they give you clues. They’ll say, “You know, I just don’t want her to…” or “I’m afraid that it will….” This gets you into performing the negative—which you can’t do. These are all big fear indicators. I will say in that moment: “That’s really interesting that you don’t want her to do ‘X’—let’s see what happens if she does. Let’s just take one run at it and let her be as much a bitch as possible, as big a racist as possible, as horrendous a sexist as possible. You don’t want her to be a loudmouth—but what’s going on right now is that I can’t hear you. So, let’s do it the other way—let’s have her be as loud as she can. Let’s find the places where loud is exactly appropriate.”

How do you begin your process when you start to work on a play?

Especially with students, but occasionally with professionals, one of the first things I say is that I won’t let them look bad—that I will tell them if it’s ugly and help them make it better. But in exchange for that promise on my end, they have to be as fearless as they can. If I’m holding out this net, you’ve got to jump.

Invariably there is some element of table work. There are inside-out actors and outside-in actors, and I don’t want to leave anybody out of the process, so I try to find a balance: What is the moment when we understand the play well enough for them to begin to take some ownership and get on their feet?

How much responsibility do you allow the actors to have in the process?

I think that the actors have to bring something new every day. Without that, it would be a really short process. You know, I can dictate a production in way less time than it takes to rehearse one. Most of the time I don’t rehearse to find the one way for something to be done; I’m looking for a range of responses to a given moment.

I tell young directors that they don’t have to have the only idea in the room—their job is to ensure that there is an idea in the room. I encourage them to hold their ideas for the end. The director has a fear of not being in charge—so I try to help young directors recognize their own fears of being judged as artists.

So many times, I’ve heard actors say—and it makes me very sad—that they have to train themselves, or their acting students, to be director-proof.

I think that “director-proofing” is bad language for trying to instill in actors a sense of responsibility for their own process. When a director says that the whole section needs to be louder, the actor should know how vocal production works so that she can do that. And if a director says it’s really important that there be an emotional response, the actor understands her own emotional process and knows how to deliver that moment. I tell my acting students that it’s about owning their own process in the same way that I have to understand Stanislavsky and Meisner and Suzuki and Viewpoints. They have to understand how to make a translation between what it is the director’s asking them to do and their acting training.

When you teach acting, what is your goal?

It’s very interesting that a lot of my time with the actors is spent actually trying to see them. They come in with “actor voice” and “actor posture,” all of it intended to show me that they’re actors—when that is a given. A very frequent note in my acting classes is: “I would love to hear that line in your voice.”

And how do you get them to do that?

Repetition is part of it. And part of it is reassuring them that, in fact, their voices are adequate.

What kind of actors do you like to work with?

I like actors who are bold—who make big choices. I like actors who prefer to do, rather than to talk about it.

How can you see that in an audition?

Sometimes I give an adjustment and I get three questions. But, if I give the adjustment and say, “Is that clear?” and the actor says “No, but I’ll give it a try and see what happens”—I love that response. With some actors, there is a sense from them that if they can get me to over-explain myself, there will only be one possible choice for them to make. That is not a brave actor. It’s the actor who makes the choice in the midst of many choices who is a brave actor.

Why teaching?

Coming out of my undergraduate studies into the world, I wanted to make ethnically specific work. There were a lot of people who were untrained, but just, frankly, brilliant. And so I needed to get more training so that I could go into my community and help people who wanted it but didn’t know how to do it. I want people who are outside the process to have a way in.

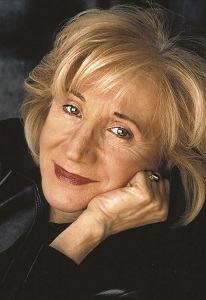

OLYMPIA DUKAKIS

New York University

Dukakis is a guest master acting and directing teacher at New York University, where for 15 years she was on the faculty of the graduate acting program. She has done similar work at universities and acting studios including the Michael Howard Studio, the Actors Center and many others. Best known to the public as an Academy and Golden Globe Award–winning film actress, she is also a regular on the New York and London stage and the veteran of more than 130 regional stage productions in the U.S. She spent 17 seasons at Williamstown Theatre Festival in Massachusetts, and for many years led her own company, the Whole Theatre Company of New Jersey.

Why do you teach?

I started to teach 42 years ago—I got pregnant and I couldn’t do any acting, and I thought, well, why don’t I just get a group of people together and teach beginning acting classes? Basically I taught them what I knew. That’s how everybody pretty much starts—start with what works for you and what you were taught. I think I charged, like, 10 bucks a class.

Then, my teacher Peter Kass got involved in starting a graduate program at NYU, and he invited me to come. He said there was going to be a company: “You’ll act, you’ll teach, you’ll direct.”

Did it end up that way?

No. The company never happened. But the teaching happened.

How was it?

Well, that first year, I was incredibly anxious and overworked. I asked Peter to give me some feedback. He was a terror, a very powerful figure. No one could believe that I asked him in. But I trusted him, totally. I would say to him, “I can’t do it anymore. It’s so boring—I don’t give a shit about them. Does the world really need another actor?” (Laughs.) And so I said, “Come in and watch me.” The first thing he told me was to stay in my chair.

What I did at first was take responsibility for everything: getting up and acting with them, improvising with them, shadowing them, devising exercises to get immediate results—so that I could think, oh good, they did it. But what happens if you, the teacher, take responsibility—you deprive people of the opportunity to take responsibility themselves. Actors need to feel that they can do their work no matter what the process is, no matter who they’re with. You’re not going to get that if somebody takes responsibility for you; and you’re not going to get that if you’re locked into one approach, unless you work only with people who do that one approach. That’s why Peter told me: Stay in your chair.

We come from an educational system that is set up to please the authority figure, so I break it down directly: I confront that moment after a scene when all the actors look at you, the teacher. I say, “You turned out and you looked at me.” I try to give them perspective. “Look, you’re going to know me for a year. I’m going to be a funny name in the future; you’ll say, ‘I worked with Olympia Dukakis.’ I cannot be more important than you.”

What made you understand that as a teacher?

This was Peter’s idea—of being independent and resourceful so that you can survive. That was in me, not only to take responsibility for myself, but to value who I was. This was very hard-earned for me. I had to fight to find my way to my own true sense of self because there was pride pulling me to be Greek, pride pulling me to be American. I spent a great deal of my childhood wrestling with that in my own way. For me, I found sports was the way to deal with it. Sports is about winning; it’s about having skills. It was no mystery: You got good by practicing. Interestingly enough, I was not as good at team sports as I was at individual ones. (Laughs.)

The European model has at its heart a uniformity of training for everyone. But that is not the case here. We don’t even have a national theatre. The regional theatres don’t have resident companies that learn to work with each other. So, what you need to train an American actor to do is to have an approach and skills that make it possible to work in different kinds of arenas with independence. And, as an actor, you have to really know yourself, you have to know what’s going on in you, you have to know what you’re choosing and not choosing and you have to embody it, vocally and physically, psychologically. And emotionally—we, as actors, have to build tolerance for expressing our feelings. It takes time. It’s a process.

Can you say more about that?

We don’t want to experience emotions—they feel so out of control. We’re not the person we want to be, or we’re not the person we want to be seen as. And sometimes we’re afraid of what we’ll do with our feelings. People say, “What are you getting angry about?” “There’s nothing to cry about.” Anger’s gone. Pain is gone. “Now look, there’s nothing to be afraid of.” Fear is gone. The only socially permitted emotion is joy. How do we claim these other feelings as valid, appropriate, human—so that you can express them and have them available if you need them as an actor?

I’ve gotten a little taste of your teaching, and you are so responsive to whatever anyone brings into the room, as well as the difference between skills and the craft.

There are three kinds of actors: the ones you teach skills to, the ones you teach craft to, and the ones you prepare for a life in the theatre. You organize your energies around each person differently.

Usually you can see the people who, for whatever reasons, are comfortable being active. You can see the people who are comfortable with feelings. You can see the people who are comfortable with their bodies. Action is a skill. It’s like tennis—you have to work on your forearm. Emotional life is a skill. Tactics are a skill. I can tell students, “I’ll tell you what I think you need to work on here—actions.”

And, this isn’t the craft yet?

No—because people come to scenes with a ball of yarn for emotions and a ball of misconceptions for actions. So what you have to do is give them the opportunity to know themselves, to know what they’re choosing. And so you make it clear that we’re not doing the scene now—we’re using the scene to work on action or tactic or emotion.

Just as the students have to learn tolerance, you, the teacher, have to sit there and tolerate the process as they find their way. The process of finding one’s way is being taught at the same time that everything else is being taught.

And that’s why I wanted to teach teachers, because I wanted to communicate the dilemma: You’re going to have to do what the students are doing. You can call the shots for yourself. You’ve got to respect yourself and the fact that you are a teacher, and this process for you is going to evolve.

WILLIAM ESPER

Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey (retired)

Esper is the founder of the BFA and MFA professional actor training programs at Rutgers University, which he headed from their beginnings in 1977 until his retirement in 2003. Under his leadership the school achieved national recognition as one of America’s top five professional actor-training programs, and in 2003 he was awarded the Warren I. Sussman Award for excellence in teaching. Esper has been the head of his own studio in New York City since 1965. He is a graduate of the Neighborhood Playhouse School of Theatre, where he was trained as a teacher and actor by Sanford Meisner, with whom he worked closely for 15 years. A Back Stage readers’ poll recognized him as the best acting teacher in New York in 2006 and 2007. He has directed more than 100 plays, and has directed and acted both regionally and Off Broadway.

Actors have such a strong desire to please whoever is watching them. How do we address this in their training?

That’s what makes them actors.

But, there must be some kind of independence—a kind of working for themselves—right?

That is a two-edged sword to actors because the very thing that makes them want to act—really have to act—is that they particularly want to please. What did Dorothy Parker say about actors? “The whole world’s love is not enough; one man’s love is too much.” (Laughs.)

But real artists are inner-directed. You can’t make art for other people. I mean, if you do it for other people, you’re going to make bad art. It has to be done for yourself. That’s part of an actor’s journey, learning that creativity is very personal and that he or she is a unique individual. The cultivation of that uniqueness in each actor is very important. I think Sandy Meisner understood that and acted on it.

You have to bring the actor, eventually, to a place where the craft belongs to him. There are no lessons to be learned; there are principles to understand, and habits that have to be drilled into the person. That’s what craft is all about. And it’s when the craft part of it all becomes unconscious that you can put all of your focus on questions of interpretation.

Everyone says to the actor, “You have to be yourself.” But then the first question the actor’s got to ask is, “Okay, I want to be myself. But who am I?” And that question can’t really be figured out intellectually. Everything we do in the first year is meant to push the actor into total spontaneity and to take away from him the ability to think. The way exercises are set up, it’s as though there is no opportunity to think because the actor’s so focused on some task that he’s performing—some complicated, difficult task that takes his whole concentration even just to attempt it, so it ties up his whole conscious mind. He’s constantly being thrown off balance, off guard, and can’t watch himself, and that’s when all the good stuff starts to come out. The inventing of obstacles is a big part of the training.

The only real way I know how to combat a lack of confidence and independence is getting them to a point where they really know what they’re doing. There’s nothing like really knowing your job to give you confidence.

And, there’s no such thing as being perfect. You’ll never get the perfect performance. The people who are so serious—they want to get it, you know, and they want to do good work—they are so desperate about it—they can’t relax enough to do good work.

Did you experience that desire for perfection yourself, studying with a teacher as important as Meisner? Did the attempt to please him overpower the work?

No. (Pause.) I mean, the bar was set very high. And his sense of truth was unbelievable. And his eye, for seeing into people, was very good. And so…(long pause)…you knew whatever you brought there had to be the very best that you were capable of.

Was Meisner an authoritarian presence?

Very much so. He followed the premise that he was there to teach something and we were there to learn it. (Laughs.) I feel the same way. I’m an expert in this particular area and I’m here to teach you and you’re supposed to be here to learn. And that’s the agenda.

But on the other hand, Sandy Meisner was extraordinarily sensitive toward good work and also in understanding the nature of the young artist’s struggle—that actors should feel entitled to struggle, to fail. That’s very important. He used to say it’s okay to fall on your face—endlessly—as long as you’re falling in the right direction, diving after the right thing.

I always tell students this story about Thomas Edison: At one point, while he was trying to invent the light bulb, he had gone through 1,700 different substances trying to make a filament that worked—and none of them worked. A friend of his said to him, “How can you keep pursuing this, in the face of all these failures?” And Edison said, “Failures? These are not failures—these are discoveries. We have actually discovered 1,700 substances that don’t work. Now look how much closer we are to the one that will.”

I think sharing stories like that with students helps them understand that you understand. And that you support them in the struggle—as long as they’re struggling. If they’re not struggling—well, then, there’s nothing you can do about that.

What does “not struggling” look like?

Well, somebody who’s superficial; who’s just going through the motions; who’s not really preparing; who has some fantasy about what it means to be an actor, without really doing the work to excel; who’s not willing to fail at it.

Another important thing is that most people who come to acting are very out of touch with their feelings. They know what they think, but they don’t really know what they feel. And, so, you have to get them out of their heads and in touch with their real responses, and in every way encourage them to express it—to say it. If somebody’s got an ugly dress on and that’s your real feeling about it, you tell them: “You’ve got an ugly dress on.” (Laughs.) The moment you start to work with yourself as an acting instrument—and I think that whole concept that you are an instrument is very important—then the only thing that counts is the truth.

Actors can’t be outer-directed. You have to encourage them to be inner-directed. I don’t say exactly this (laughs)—but, you know, I tell them just to say, “The hell with Bill Esper, the hell with the class and the hell with everybody. I’m just going to do what I’m prepared to do, and if they like it, okay, and if they don’t like it, what am I going to do about it?”

Ultimately, you want your students to say that?

Oh, absolutely.

I’ve had students come up to me in tears, saying that nobody ever, in their lives, asked them how they felt about anything. That is very empowering, as they begin to make contact with that, constantly asking themselves: How do I feel about this? What does this mean to me? How do I feel about this moment?

To have a point of view. And to acknowledge a point of view.

Yes—and to rely on the fact that this is me, this is mine; I don’t care about what anybody thinks, that’s how I feel about it, that’s what I think. That’s very empowering. And it carries over—carries over into their lives, and carries over into their dealings with the business.

ROBYN HUNT

University of South Carolina

Hunt is a professor of acting at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, S.C. She was previously a professor in the School of Drama at the University of Washington, where she taught acting on the graduate faculty and where, in 2000, she received a UW Distinguished Teaching Award. She is co-founder and director of Pacific Performance Project east and has appeared in professional theatres throughout North America, Europe and Japan. She worked with Japanese director Tadashi Suzuki for more than a decade and studied with Shogo Ohta in Kyoto. She has performed regularly at Actors Theatre of Louisville in Kentucky; Seattle’s Intiman Theatre, ACT and On the Boards; and at Connecticut Repertory Theatre in Storrs. She wrote, directed and choreographed “Suite for Strangers,” a dance/theatre trilogy, which premiered in Seattle in 2004.

Why teaching?

It starts with my dad, who is such a brilliant teacher. His route was of the physical also: He’d been a professional athlete, and he was coaching when I was growing up. Track and gymnastics were his two favorites because he said the individual could shine—but then the overall team is what made them win. His was the first model. Early on I had examples that life could be changed in a fundamental way by this direct contact between teacher and student.

For me undergraduate school coincided with the civil rights and Vietnam War protests—and so I started to see this amazing idea that teaching could be a social activity whereby I could play a part in reminding learners that a single voice is potent.

My minor at the University of California–San Diego was the sociology of education. I analyzed transcripts from elementary school classes, looking at what kind of signals went out to learners to discourage or encourage them. That analysis seemed so far from the stage at the time and yet I think that it has served me very well: It primed me for paying attention to the cues that I give and that there could be a miscommunication, despite fabulous intentions.

What kinds of cues?

I’m thinking of things like, “You have to fight hard.” A learner, in an effort to please, could think that “fighting hard” means a bearing down or a tightening. To achieve centering, that learner could think that there should be a kind of physical sensation in the center, which could cause him to tighten, when in fact that would be the last thing you would want to happen.

I would say maybe the most significant thing is to make sure that the cues one gives as a teacher have to do with the learners’ ultimate independence. In fact, it might be the main thing one teaches. I’m teaching them to be resilient, courageous, energetic, hungry, curious and particularly to have a sense, to develop inside oneself something that I have been calling the unassailable core. Nobody can get at it, nobody can steal it from you—and you have to develop it.

How do you help them to do that?

First you have to acknowledge that it’s possible that there is a place that no one can get to. It’s of course what those who meditate are interested in—it has to do with breathing—and I think that a lot of the slow tempo work helps people to find that. They have to go way deeper than the way they previously thought of concentration being, in a sense, a demonstration to the director that you’re working hard. There’s someplace way deeper to go, where the director then would just be witnessing the process.

How have you reconciled the need for that “unassailable core” with the desire to please—the teacher, the director, the audience?

I guess I would start to discuss this “core” with the experience I had with Tadashi Suzuki directing me as Clytemnestra in 1986. It was trial by fire: One, I didn’t know how to do what he was asking me to do, and two, if I couldn’t figure out a way to make major progress, I would have to give up acting, because I would never be able to live with myself. I remember standing there, and I couldn’t open my mouth and tears were running down my face because I knew what was at stake.

What happened in rehearsal?

He would say that I was too psychological. I didn’t know—all I had been asked to do up to that point was what Suzuki was calling psychological. He wanted it in the whole body and he wanted it huge—it was a Greek play, for goodness sake!

What was it you were confronting?

I was afraid to make that kind of sound. I think I was instinctively afraid of how it would look kind of primal or sexual—

That you would feel too out of control?

Too out of control personally, but also, so ugly and so naked and so foolish. I was confounded too, because in my fear to take a chance, I realized how safe I had been playing it for more than 20 years. And that was its own recrimination.

Finally, it came to a run-through at which Suzuki had his whole company, and all of his assistants, and all of the Americans. We were rehearsing Clytemnestra’s big entrance and Suzuki stopped me, and he stopped me, and he stopped me. I must have done it 15, 20 times—that’s not it, that’s not it, that’s not it. I was feeling completely exposed: I’ve come all the way to Japan, I’m 35 years old, I’m someone who teaches acting. Everybody was watching. At one point Suzuki stopped everything and said through the translator, “Why are you so good at my training and so bad on stage?”

There was a moment in which I wanted to wail and cry and quit—but that was not tenable. And something happened. I don’t know what to call it. It was all at once—I felt slammed against the wall—it was like I knew that Suzuki couldn’t get to the heart of me—even though he was seemingly attacking me—there was something in that moment I realized that he couldn’t ultimately hurt or touch. And it had to do with who I loved and what my favorite flavor of ice cream was…. All of that is a little too literal. But there was a sense that there is some place where I can go to now and I can rest in—even as he is nailing me to the wall, I can find protection there and I can keep working.

People watching said that I looked like I suddenly got taller. Whatever happened, I received his fierceness, and I took a minute, and after that was the most astonishing change. He stayed as hard on me—but it didn’t matter. Everything in the rest of my life has changed because of that.

We kept rehearsing that night. And inside—everything was different. I’ve never forgotten it. The next day, Mr. Suzuki’s assistant walked by and she said, “He said to say you got better.”

So, before that moment, there was not only a fear of failing yourself, but of failing Suzuki—and others’ expectations of you. Do you think in that change you reached a place where you could work only for yourself?

The ultimate answer is yes. But I would put it a little differently. It’s not for myself. It’s for it—the work. It’s neither for me nor for the director, it’s this idea of something splendid or something beautiful or something remarkable or something transcendent. That’s what it’s for. Once you’ve experienced this thing where you can feel there’s insulation between you and the people watching—between you and approval or disapproval—it means that you can work. It means you can rehearse. And you can take chances and you can be fearless.

And how do you teach this?

I’m trying to be in the service of finding the way to do it, and I haven’t arrived yet. But I think it starts with naming it, so that learners can believe that it’s possible. As soon as you describe self-consciousness as the primary inhibitor to good work, then you start to create an appetite for the alternative.

When I describe that self-consciousness, I call it the “satellite loop.” That is to say that self-criticism beams out to the director’s eyes like a satellite, and then comes back at me doubled with the director’s scorn. By now, I’m nowhere near actually rehearsing, and now the action becomes not what the character’s action might be, but what do I need to do so I don’t feel foolish.

Obviously your acting was deeply affected. How has your teaching been affected?

One of the ways the teaching has changed is that I read what I see differently. So, if the head is working overtime—if the head and the analytical mind and the brain are going like crazy and the body is dead, we have to start over. And because this is one of the central problems, it means that every moment of diagnosis is changed.

MARY OVERLIE

New York University

Overlie has had a long and respected career as a performer, choreographer, teacher and theatre collaborator working extensively in the U.S. and Europe. She is a founding teacher at New York University’s Experimental Theatre Wing and is writing a book and designing a certificate program for the Six Viewpoints, a performance technique she originated. She has worked with Paul Langland, Nina Martin and Wendell Beavers, who formed her core company from 1976 to 1980, as well as theatre directors Lawrence Sacharow, Lee Breuer, JoAnne Akalaitis and Anne Bogart. She is a founder of Danspace at St. Mark’s Church; Movement Research, a dance co-operative nearing its 30th year; and the Pro Series, experimental dance workshops designed for the Tanz Wochen, the summer dance festival of Vienna.

Your classes are not called acting classes; they’re called movement classes or Viewpoints classes. But, they are, in fact, acting classes—how?

I think that it’s acting that has been flipped—over onto its other side. I think that acting as we know it, in Western forms, started with attempts to make what the actor was saying believable to the audience. And so there’s an attempt to mimic real people’s emotions and actions—that part of what we see in people—you know, there’s a lot of stuff about people that we don’t focus on. We focus on their story and how they feel. Acting is filled with these two things—and on a sense of copying.

I have to say that what Stanislavsky achieved—he fills up that history wall to wall. There’s no one else as significant, as in-depth. Because he created such a substantial interior to produce emotion. But it’s still replicated. That’s where the Viewpoints flip—because Viewpoints don’t replicate, they are. Viewpoints are really about the development of awareness—which is a meditative, interactive process—and so, in the incremental development of awareness, one is drawn into dialogue and dialogue is action. And, so, in a certain sense, the idea of internal and external is erased. In Stanislavsky’s approach, there is an internal and there is an external. In the Viewpoints, there is no line like that whatsoever. The line is so erased that it reaches all the way to the audience and back.

Can you give a specific example of what you mean?

Within each of those six materials [the Viewpoints: Space, Shape, Time, Emotion, Movement and Story] is volumes of dialogue—it’s a dialogue that’s natural to human beings. We walk around in space. And how we walk around in space affects us deeply, but we tend not to notice that. The Viewpoints make the actor aware of that—of those things that might typically happen without thought or awareness.

The actor who is not space-aware tends to drift to the center of the stage and stay there—he gets rooted in space. Movement is very clumsy and he doesn’t use blocking except for the most expedient purposes: He wants to sit down, so he crosses the stage to get to the chair. Whereas a Viewpoints actor—well, first of all, just to get him to stand in the middle of the stage would just about kill him, because it’s a very, very odd place of stasis in itself. So the Viewpoints actor will choose where he is going to start the scene spatially and that choice—whether it’s the upper left hand corner of the stage, or wherever it is—that choice is integrated immediately on a psychological, emotional, performative level—he is performing upper left hand corner.

So is there a way that Stanislavsky and Viewpoints can meet?

Oh, absolutely. It’s thrilling. Look at the world of dance: The dancer who has studied ballet, and then Graham, and then contact improvisation, is one mighty interesting person. It used to be thought in the dance world that you couldn’t do that—that they were muscularly, psychologically, alignment-wise, in complete opposition to each other. But that line of thinking belongs to those who are making fortresses around something, for defense and superiority. It turned out to be breathtakingly not true. And I think it is the same with Stanislavsky and the Viewpoints—of course, it’s a better actor who has studied both.

How do you begin to teach the Viewpoints?

Well, the horizontal is so central to the Viewpoints that you can’t have one without the other.

Okay, what is the horizontal? When you walk into a classroom, how does it show up?

First of all, it is not allowed for the teacher to know something that the students must learn. That transference is not allowed in the classroom. The teacher is in the lab with the students—it is a horizontal relationship, not vertical—and there are rules about how to get that established. The teacher must be as exposed, or more, than the students are—as an invitation to neutrality. Right away it removes that the teacher is on any kind of hierarchical level. You are not the final authority. It’s all right for you not to know. You can get discouraged, sad, found, happy, egotistical, opinionated, angry, distracted.

What does a class with you look like?

I arrange myself in an awkward position on the floor, lying on my back with my head propped up by a wall, reading a newspaper. And they come in, and I don’t even say hi to them. And so they’re left trying to figure things out raw, on their own—what this class is about, what the rules are—and that carries on for a number of classes until they realize that there is no authority figure in this room, except themselves.

But you do have knowledge that they don’t have.…

I am a master at setting up situations in which they can have really powerful experiences.

How? Give me an example.

This year, I had a particularly gorgeous group of students—they were just 100 percent wanting to be in that classroom. One of the problems with them was that they were super motivated and super bright, and when you have those two qualities, you expect to ace things. That can get very tricky—managing that. For example, what I wanted them to do was work on a scene which they had already memorized and acted before, and to disregard each other’s timing—which is train-wreck messy—and in the process of struggling with it, they were thrown into a situation where they had to wrestle with the person [in them] who aces things before they have fully confronted the depth of the difficulty—where they could not predict what the learning would be at the end.

Do they look to you after they’ve presented something?

They would—except that I’m not available for that. It’s already set up that I can’t help them. I don’t know. They wouldn’t even think, at that point in the class, of looking to me for the solution. But, what they do look to me for is consolation and solace. Because they’re suffering. And that’s allowed—that’s a given. That kind of suffering we do—it’s not artistic suffering—it’s real miserable groveling. And I just commiserate with them: “That really hurt—that was so ugly.” I don’t have them do it again. I just drop it. And what happens is that they can’t drop it.

So they go home with it—and they come back, two or three classes later, and they say, “Can we try that again?” And I say, “Sure, if you want to.” And, by the second time they’ve decided to return to it themselves, they’ve already taken a massive step—which is, they think they know something, which they’ve put together themselves, that’s going to help them work it out.

For this particular exercise, it took the entire semester. It was bloody. Of course this wasn’t the only thing we did—we did hundreds of things, more than a teacher would normally think to do. I don’t try to filter things to keep them organized. I’m not afraid of chaos, because I’m tracking another type of development that’s not visible: their ability to engage in their own dialogue, in their own experiences, in their own moments, in their own time, and make something happen.

Is there ever a point at which you do discuss goals or results with them?

Yes. It happens usually about three quarters of the way through the semester—late, very late. And the discussion is initiated on the premise of talking with them about how each of them goes about achieving a goal. And, then, there is some analysis about what works in that process for them, and what doesn’t work in that process for them, and what’s inhibiting.

When we start talking about goals, the discussion goes from strategy to, finally, what is the goal. And the goal is the spectacular—and, then, what does spectacular mean, how is spectacular defined, in general and also, specifically, by you in this moment? It’s a very private and very delicate atmosphere in class that day. This is a super-secret talk we’re having; we have to be protected in our effort to project into our most spectacular selves.

Do you have a goal?

(Long pause.) I do. And it’s funny that you should ask that because I actually finished the teaching year kind of scared—my classes were spectacular, and I wondered if I had really taught well. I think that, at this point, the goal of these classes is…that Viewpoints is a process—a very metamorphic process. People get frustrated, I think, a lot, around me and the Viewpoints, because they want to know what they are—and I can’t deliver them. I don’t see them as something that can be delivered in that definable way. The longer I work with them, the less I can deliver them, and the more I want to see people through the metamorphosis that the Viewpoints are and which can produce them in the first place.

ANDREI SERBAN

Columbia University

Serban has been a professor of theatre arts and director of the Oscar Hammerstein II Center for Theatre Studies at Columbia University since 1992. He has taught at schools worldwide, including the Yale School of Drama, Harvard University, Paris’s Conservatoire d’Art Dramatique, University of California–San Diego and the Pittsburgh Theatre Institute. After early studies at the Theatre Institute in Romania, he was invited as a young director by Ellen Stewart to La MaMa Experimental Theatre Center, where he directed “Fragments of a Greek Trilogy,” which won several Obies and went on to be performed at more than 20 international festivals. He has directed theatre and opera widely in the U.S. and abroad, and his 1977 production of “The Cherry Orchard” won a Tony for best revival.

How do you begin with your acting students?

Two directions. One is working on technique: on skill, on their voice and their body and coordination, on text work. And then the other side: totally free improvisation. Without technique, you cannot be free; but if you only emphasize skill, technique and rigor, then you get stuck in something that is too uptight. So, you have to know how to allow creativity to go completely wild, and then you must come back to what is called discipline. These two are always important—together.

It seems there is a very difficult negotiation between creativity and technique.

Yes. Some of the training exercises we do, dealing with counting and movement and voice exercises, require total precision. Then in the scene work that they have to present to me, I ask them to bring something that is surprising: Be original, be eccentric, be over-the-top. Always try to bring this element of surprise—because theatre which has no surprise is dead.

We are in a situation similar to that of a lab: Nobody sees these experiments. And we always learn from making mistakes—so striving to make mistakes is the best thing. You go to the limit of what the imagination can do and then you return to the, let’s say, rigor of the text—asking yourself, all those fantastical fantasies of mine, do they illuminate the scene, or do they obscure the scene?

How do you get your students to take those leaps into the imagination? Are they afraid at first?

Of course. It takes a long time. The first presentation—it is total lunacy. (Laughs.) Then, you know, I’m very harsh with criticism—extremely harsh—and they get scared. And the next time they do something which is totally tame and plain boring—and then I am even harsher. (More laughter.) Peter Brook says the devil in the theatre is called boredom.

Do they try to please you?

Absolutely. But, at some point along the road, what they discover is that the body is the vessel for all the energy of the action of the play or of the character. It’s not in the head. It doesn’t come through a kind of cloud of the imagination.

When they feel what is called presence—the presence of the actor—then everything changes. When the presence of an actor is really matching the role that he or she is playing, the actor and the role become one, in the way a glove fits a hand: The glove is not the hand, and at the same time it matches, totally, the shape and the movement of the hand. And when one feels that sense of presence, one isn’t so much worried, or panicked, about pleasing somebody else. This rush to please is there because something inside is not calmed down, something is not assimilated, something else is absent. This kind of crazy desire for approval is there—we all feel it in the theatre—but, somehow, when you get nourished by the work on stage, then that is what really matters.

What do you look for in the actors that you choose to work with?

They cannot be amateurs; they have to have skill, and at the same time they have to have heart.

Heart. How do you see that?

You can see it immediately. I can tell.

What’s the audition process for your program at Columbia?

I have a lot of callbacks. The first day, they do a monologue, a song and a dance. I can see people more by the way they sing than by how they do a monologue. The body is like a map. We are very good at trying to hide—but the body cannot hide. The way you hold your body—your posture, the expression on your face, the look in your eyes—all this cannot lie. So I can see the tensions a person has; I can see the potential for adventure or for journey.

It’s very tricky, because some people who are very good at auditions may turn out to be the same all the time—they don’t change a bit up through the opening night or graduation. And some people who are disasters in auditions may grow spectacularly afterwards. That’s why I need to see a person more than one or two or three times.

Some teachers, in the classroom, prefer a horizontal relationship between them and the students. Others prefer a hierarchical relationship. What is your preference?

I don’t believe at all in either a kind of fake dictatorship or the power of the teacher or director—nor do I believe in democracy in the theatre. (Laughs.) We joke as if I am one of them. But, when I give my observations, it is from a very clear place of authority.

The reason I work in the theatre is to discover something, always. To just teach something I know would be a waste of time. I believe that we are all searching together. I never know beforehand how it should be—the evidence is in the moment—then the critical mind has to come into play. The critical factor is very important, but if you only fulfill the critical factor, then you come to a dead end. Because then you are only dealing with the conscious, which is deadly—there is no flesh, only bones.

Say more about that.…

Well, what I mean is that the mind sucks away life. Just as you cannot make love with your mind, you cannot act with your mind. You just can’t. You have to put order into things—so the mind is a great detector, an organizer. But the real intelligence is not in the mind. The real intelligence is in the intuition. If there’s too much mind, it paralyzes the students. It takes their courage away. It takes their appetite for joy and pleasure and freedom.

How do you find that balance—not to say too much?

Through trial and error. You have to learn what it is to teach. When to stop.

How do you know when to stop?

Peter Brook has this great definition of what is a director or teacher. It’s visual. (Pushes his hands toward the listener. Pulls his hands toward himself. Folds his hands in his lap.) First movement: I am pushing, pushing. Second movement: I stop pushing and let them do it—I am still there, ready to intervene, but I am withdrawing my hands and letting the student/actor take over. And third movement: I am just watching. All three are important.

Why do you teach?

I could say, for a very selfish reason: to keep myself young. And, in the best ways, to be in connection with the powers of the young generation. In each generation, something changes, you know? But, with each generation there remains the same deep question of the human condition, which doesn’t have anything to do with young or old: Why are we here? Why are we doing theatre? What is theatre for? Only by staying with the question every day can we find out if there is an answer. Even that answer is not an answer.

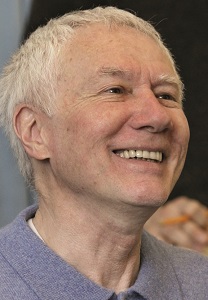

RON VAN LIEU

Yale School of Drama

Ron Van Lieu currently serves as the Lloyd Richards Professor and chair of acting at the Yale School of Drama, where he also heads the committee on diversity for the school. From 1975 to 2004 he was head of acting at the NYU Tisch Graduate Acting Program, where he also headed Studio Tisch, a developmental workshop for graduates of the acting program. He was trained as an actor and director at the University of Iowa and at Tisch. In 1993 NYU awarded him the distinguished teaching medal, the university’s highest honor for excellence in teaching. He was a founding faculty member and head of training at the New York Shakespeare Festival’s Shakespeare Lab, where he partnered for 10 years with Rosemarie Tichler. He is also a founding faculty member of the Actors Center in New York City, where he continues to teach both actors and acting teachers.

One thing that has really struck me as I have watched you teach is that you allow actors such freedom to make their own choices. How do you do it?

First let me answer why I do it. I think that the expectation when people come to actor training is that a number of things will be done to them, so that when they leave that institution they’ll have a kind of road map. That’s partly true—in that if they go to a good institution, they are going to be given sound principles of craft in acting.

But, I think the most important thing that they need to be given is the trust in their own imaginations, their own humanity and their own sense of artistic license. They’re often surprised when that is offered to them. I think it takes a while for them to believe that, first of all, as creative people they’re entitled to do that and, secondly, that it’s wanted. Too often they think their job is simply to show up and do whatever they’re told.

What is it you look for when you select actors for your program?

The first thing I look for is individuality. People who are themselves. Who can sit down and talk with you, without trying to figure out who you want them to be; who are at home in their own bodies. And then I look for an active imagination, which, to me, is the ability to believe in the given circumstances of a play as if they were real. It’s the difference between an actor who illustrates—who is basically a mimic—and an actor who lives within. A collaborative spirit is also very important: that they’re not soloists, that they like to play with others. And I like people who have a lot of courage—because there is so much fear in the profession. And fear is, to me, the great enemy of creativity.

How do you see that courage?

They seem open to possibilities. If you work with them on material, they are not resistant to change. They’re not fighting themselves or you while they do it. Their bodies are not invaded with a great deal of tension. Nor are their voices. They seem to have a fluidity of emotional life moving through them. In other words, I would say they seem flexible.

How do you begin scene study with a group of actors?

I usually use an American realistic play. I ask them to read the play and to pick a character they feel excited about the possibility of acting. I ask them to make a list of all the character’s attachments, and I ask them to get interested in answering five questions: Where am I, who am I with, what do I want, what am I doing to get what I want, and what are the consequences if I get it or don’t get it? And then I bring them in without any rehearsal and with a script in hand, and I start working with them on what are, to me, the basics of how to work together.

The first point is that the text is the means of reaching one another—so that they’re always putting their main concentration on the other person, not on themselves. I ask them to understand that acting is both giving and receiving: You are trying to penetrate the other person and you are trying to be open and receptive to the other person. That exchange is the flow of life in acting.

And this is before you ever enter the physical world of the characters?

Right. I’m really on the lookout for what their habits are. I’m trying to discern what I think they are presently able to do which serves them as actors, and I leave that alone. And I’m able to see the kinds of things that aren’t serving them well—which are usually habits that they probably aren’t even aware of. I begin to try to give them alternatives to the employment of those habits.

For example?

One of the most basic habits is when people hold their breath every time they get close to a strong feeling. In life, it’s appropriate; in acting, you have to do the opposite thing. If you want to be able to release a feeling, you have to breathe into a feeling.

Usually, what I see is actors living in anticipation of everything—always ready to do the next thing, before they’ve taken in the present event. The fear actors have of doing something wrong is why they anticipate: They want to be ready and they want to do it right when the time comes. So maybe the most basic thing is to encourage them to find the lives of the characters more compelling than the fact that they are acting.

Have you found that you’re unable sometimes to get them past that?

It takes some actors a much longer time to trust that they can enter the work with a kind of openness that precludes so much preparation—and also that they will be able to come up with the result that’s going to be required. I try to encourage them to make the process so deeply involving, so personally engaging, and so useful of their imaginations that that’s their real delight in acting, and that whatever result is being asked of them will come out of the process in which they’re working.

You have such a specific and sophisticated way of bringing that out of them—can you articulate it?

Maybe I’m more of a coach than I am a strict definition of an acting teacher. There are basic principles that I do teach, but I’m most interested in how the person in front of me is using those principles. I won’t always do the same thing with every actor because I’m really interested in who that person is and what his or her imagination could release. I guess I’m looking for actors to appreciate that about themselves, not to erase themselves in the name of technique.

Did you have teachers who really stood out to you?

My first teacher was Joseph Anthony, who taught the Michael Chekhov technique. He was the first person within the profession who gave me the confidence to believe that I could be an actor.

The next was Lloyd Richards, who was my first acting teacher at NYU. He opened up my mind to the idea that you bring yourself into the world of the play, and at the same time you need to develop enough technique to transform parts of yourself into the character. And Olympia Dukakis helped me understand how to really, deeply do that.

Another great influence at NYU was Omar Shapli—he was a brilliant teacher of theatre games, based in Viola Spolin. From him I learned the joy of spontaneity, that acting is really a form of serious play, how to tap into my intuition rather than my sense of logic. I learned what it means to “be in the moment” from him.

Why do you teach?

I never planned it. I started teaching at NYU in 1975 as a substitute for Olympia. NYU offered me a job because of that. And I said I would only take the job if I could continue acting also. So, from 1976 to 1981, I combined teaching with acting. But during that period, the pleasure and the creative satisfaction I got out of teaching began to clearly feel more important to me than what I was getting out of acting.

Do you ever find that your reputation as a teacher—which is far-reaching at this point—can be paralyzing to your students?

Yes. Exclamation point. (Laughs.)

So how do you handle that?

I try to be as human and as accessible and as open as I expect them to be. Sometimes I resort to sheer clowning and self-imitation just to clear the air a little bit. And I try, as much as I can, not to fall into a directorial role within the room. I try to keep it about them: I’m not always answering the questions; I am offering the questions. They don’t always have to look outside themselves for the answer; they are in possession of the answer.

I think it’s the responsibility of all of us teachers to encourage actors to think independently and to value their individuality and to bring that into the work. Because I do think the profession conspires to take those things away from the actors. There is an art to acting. There are, in a way, rules—so that you’re working within an art form for which there is a form. But, it’s not just the form. It’s also the degree of freedom that you can find within that form. So, I use the phrase “freedom within form” all the time—just to keep reminding people that that is, ultimately, the goal.