Catherine Fitzmaurice, founder of Fitzmaurice Voicework, was born in India in the waning years of British rule of the subcontinent. Her grandfather had been a judge there, and her father a member of the Indian Civil Service. When she was seven her family returned to England and then Ireland, where her father was born, and she was sent to English boarding schools in Surrey and Hertfordshire. In our conversations, Fitzmaurice and I discovered a mutual fascination with the East, combined with a deep embarrassment over our heritage as citizens of an ex-colonial power. “It simply does not accord with my inclusive politics,” Fitzmaurice says. Her later incorporation of Eastern philosophies (such as yoga and shiatsu) into her celebrated voice work resonates deeply with my own spiritual journey, and in our conversations about the voice we found common ground.

Fitzmaurice spoke fondly of the English boarding-school education she received. She recalled her early fascination with words and poetry and how it was fostered by her teachers. Those early years prepared her for the tutelage of Barbara Bunch, with whom she studied from age 10 to 17, setting the stage for her acceptance by the Central School of Speech and Drama. Studying further with Cicely Berry and others, Fitzmaurice distinguished herself: She took first place, for example, in the English Festival of Spoken Poetry, a competition in which the actor Vanessa Redgrave placed third that year. It’s hard to exaggerate the influence of verse-speaking upon voice teachers of the generation to which Fitzmaurice and I belong. In my own case—at the Rose Bruford College of Speech and Drama, where I trained with teachers of the same provenance as those Fitzmaurice encountered at Central—verse-speaking was the chief pillar of the training. The English Festival of Spoken Poetry, sponsored by Edith Sitwell and T.S. Eliot, had an enormous influence on the generation of voice, speech and acting teachers to which we belong.

I first met Fitzmaurice while attending the annual conference of the Voice and Speech Trainers Association in the early ’90s. She gave a remarkable master class, and I will never forget the kinship I felt with her, both of us expat Brits (or Irish, in her case) bringing the classical voice training we inherited to America. She asked me to perform a piece of Shakespeare—I forget the passage—and in our mutual appreciation of the demands placed by the text upon the mind, the body, the breath, the soul, I discovered that we were both heirs to a classical system that valued the twin sciences of music and mathematics. Her ability to find freedom, release and transcendence at the same time had a deep impact on my thinking.

While she was teaching at Central, Fitzmaurice met her husband, David Kozubei. He was (to quote Fitzmaurice) “a bookman,” a manager at Better Books in London’s Charing Cross Road. When they took up residence in Ann Arbor, Mich., he created the original Borders Books (“though sharing in none of the immense profits when that company went public,” Catherine wryly observes). One of their two sons, Saul, is among the eight master teachers designated by Fitzmaurice Voicework. David, her husband, died in 2006.

The story of Catherine Fitzmaurice’s rise to become one of the half-dozen most influential voice teachers in the theatre is well documented, and this introduction does not need to recount the roster of acclaimed directors who laud her work, nor the famed venues in which it developed, nor the names of the actors who testify to the power of her work. You may visit her website here or at any of the more than 4,000 pages offered by search engines in response to a search for Catherine Fitzmaurice Voicework. Her legacy and enduring influence are secure. She has passed the torch to hundreds of certified Fitzmaurice teachers, who work in conservatories and theatre schools all over the world.

PAUL MEIER: You have a unique approach to the performer’s voice. What shaped your approach? Who were your major influences?

CATHERINE FITZMAURICE: My approach is unique in some aspects, but also deeply classical. I received training from age 11 to 17 with Barbara Bunch, an alumna of the Central School of Speech and Drama, who had also taught Cicely Berry when she was a child. Then I worked with Cis Berry and others at the Central School for three years. After returning there as a teacher, I discovered Wilhelm Reich, and that encounter was the profound shift that started me on a lifelong quest for new ways of looking at a) the world, and b) the voice. In doing Reichian work, I experienced tremoring.

What exactly is tremoring?

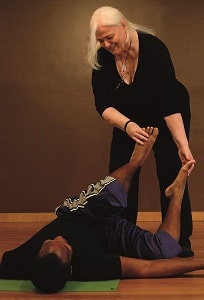

Tremoring is a naturally occurring reflex in the body, quite different from intentional shaking. It happens when you are cold, angry, excited, injured, fatigued, nervous. Neurologically it is based in the autonomic nervous system rather than the central nervous system. It is tremendously useful for voice, because it directly reaches those aspects of oneself that are almost impossible to identify and shift. I’ve developed ways to encourage tremors to allow spontaneous breathing and to release chronic muscle tension.

Could you address the immediate usefulness of your teaching, both to classical actors and to singers?

When actors and singers become aware of spontaneous breathing, they can address how best to avoid pushing, to avoid giving the impression of trying or struggling. Tremoring also affects resonance as a result of releasing muscle tension; you get a fuller sound, because the body is more accepting of vibration. If you were playing an oboe and you put your hands around it, you would deaden the sound. That’s what muscle tension does to resonance in the body. With freedom to vibrate you get a fuller complement of fundamentals and harmonics in the tones. And tremoring gives people a sense of ease in general.

Talk about protecting the voice, if you will.

The voice work that I hear in many contemporary singers (less so in classical singers) and also in a lot of acting work reveals misuse of the voice. There is such a sense of struggle and pain and tightness. Tremoring brings one back to organic flow so that production of voice becomes easy. The brain is following reflexive impulses rather than trying to follow conscious instructions for vocal production. It’s not trying to be right. It settles into an organic, easy way of production, which is everyone’s natural birthright. And restructuring gives them healthy vocal habits.

This might be a good time to ask you about the terms you are so strongly associated with: destructuring and restructuring.

Those fell out of my mouth one day in class in the early ’70s, and I’ve been using them ever since. I think when I said destructuring I was trying to introduce and apply the concept of deconstruction, and the word simply came out wrong. I liked my new word and, as you say, it has become associated with my work. It is primarily about getting rid of what is familiar, what is habitual, what makes logical sense, what other people are asking you to do. And the restructuring is putting things back together from a more aware place, coming back to a very strong sense of focus, intention, functionality and structure in the work—but in a way that is simple, healthy and effective, while remaining organic.

How might the working actor or singer interested in training with you get into your program? How long would it take?

It could take place in any number of ways—in classes, workshops or private sessions. The culmination is the two-year certification program for people already familiar with the work. Some people study it in school and then come directly to the certification program, although I do recommend that they first attend a five-day workshop. If people are starting from scratch, they can start with workshops or private sessions with any of the certified teachers listed here.

Let’s jump to speech. I was interested in how stage dialects are handled in your training system.

I used to teach them, but only those that I grew up hearing. I have worked for many years with Dudley Knight, who is exceptionally clever with dialects and accents. He and his colleague Phil Thompson teach in my program. Fitzmaurice Voicework is a very porous system in that it is accepting of other modalities and of the particular passions and interests and skills of each participant.

How is your research evolving at present?

Improvisational speaking interests me a lot at the moment. I’m exploring that in various ways. I encourage people to speak in a completely spontaneous manner—while they’re tremoring, for instance, or in response to someone else’s improvisation. As one explores what the voice can do in non-logical ways, the paralinguistic aspects of voice and language are highlighted. It’s language, but it’s destructured language. I am also working with my son, Saul Kotzubei—a Buddhist scholar, professionally trained actor and clown, and voice coach—on presence, meaning a very full sense of awareness of yourself, and of how you are being received, by whom, in what circumstances, and how all of this may impact your speaking. I understand Patsy [Rodenburg] is teaching the notion of presence in her work, too, though perhaps we mean something slightly different by it.

You are getting at the question of reciprocity between sender and receiver.

That’s a great word, reciprocity. Between the speaking and listening and the reacting and re-listening, something absolutely unique, and uniquely timed, gets invented. I watch these events, and I often wish I had them videotaped, but then I realize that the work is so of the moment that maybe it shouldn’t be.

As you know, Kristin Linklater, Arthur Lessac, Cicely Berry, and Patsy Rodenburg are all featured in this special issue. What are the similarities and dissimilarities between your approach and theirs?

Our work is much more similar than dissimilar. But, of course, there are differences. We are different people, we have different personalities, our histories are different, and our specific interests are different. Cis has continued and built upon the whole Central voice tradition and taken it worldwide. Arthur came on the scene in the United States, and his contribution was to develop a system that is interesting and clever and effective. He’s now 100 years old and a perfect example of the vitality and energy that he teaches. Patsy has the same training as I do from the Central School of Speech and Drama, so there is similarity in our understanding of voice production. Kristin was trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art by Iris Warren. Kristin’s work is similar to mine in that she is, to a certain extent, interested in freeing tension and in the impact of breathing. But what essentially differentiates my work from all of these is that I initially explore breathing and sound-making while students are in the reflexive state of tremoring, when they are giving over completely to spontaneous behaviors rather than trying to learn something, which is a function of the conscious mind. I hope that makes sense.

It does. What, in your opinion, are the major mistakes professional actors continue to make? And if there were only one technique or skill you could give them, what would that be?

I think the major mistake actors make is in thinking that voice work is about making a “good” sound, and that it comes from the larynx. So they are employing unnecessary physical tension in order to create sound. I would most like to teach people that a wide range of sounds that convey clear meaning is acceptable, so long as there is healthy functioning, which requires use of the transverse [transversus abdominis muscle]. Other than all the destructuring work I do, including tremoring, the one essential I use is the engagement of the intercostals and transverse to support the voice; and then the applications of voice work, including singing, speech and text work, all rely on that. Yet I’ve also worked with actors in production who primarily needed and wanted to tremor. I’ve done this with Kyra Sedgwick, Val Kilmer and Dianne Wiest, for example. They ate it up—they loved it. For those for whom it seems scary, I would say just try it, because it’s fun!

Paul Meier, a dialect coach for film and theatre, is the founder and director of the International Dialects of English Archive, as well as the author of Accents and Dialects for Stage and Screen.