Her obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle begins: “Beloved Bay Area actress and clown…” When she got sick last year, fellow performers put on a benefit that filled the 1,000-plus-seat Geary Theater, donated for the night by ACT. The event ended with a thundering ovation from the Bay Area theatre and circus community, honoring an artist equally beloved for her magnetic, usually hilarious performances and her uncounted acts of generosity.

She was in my first original play, and 40-plus years later, in one that will be among my last. In both she played working women—one young, one old—caught in the eternal job/family conflict.

But I’ll start with generosity. I twice knew Joan to quit a role she loved so someone else would get a chance to play it (then was surprised when it wasn’t given back). Once when I told her “today’s my birthday,” she pulled a ring off her finger and told me to take it; only when I showed her that I was already wearing one, a gift from her and another friend on another birthday, did she take it back. For a collaborator who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis soon after directing her as the Pickle Family Circus’s first female clown, she helped organize a companionship and support team that’s still working. In what turned out to be her next-to-final season, she took in a dying friend and turned her house into a hospice for a year and a half.

She was a creature of impulse. Her impulses were often mischievous but never mean (though fellow actors could be unhappy when she succumbed to one onstage). In the 1970s, the age of ensembles, she quickly moved through the local list, not from any hard feelings but so she could try new things: from the San Francisco Mime Troupe, where she and I met, to a feminist theatre named Lilith, to Dell’Arte Players, to the Pickles. She was welcomed back to work at all of them. Directors fumed, “She never does the same thing twice!”—then cast her again, for her magnetism. She was never not in a show: She worked everywhere, from the aunt-and-neighbor roles at the regional reps that are most of what’s left for Bay Area talent, to leads up and down the small-to-midsize range, to tiny community theatres. At times I wondered: “Does Equity have a special LOA for Joan?”

Old SFMT friends were slow to be alarmed by odd behavior that signaled her fatal illness. We said, “That’s Joanie,” remembering incidents like these:

- A director calls her from rehearsal: “Where are you!!?” Joan: “I’m fucking.”

- On tour at the University of Nevada–Las Vegas, the SFMT, at first quietly, loads into a room during a “Mother-Daughter Fashion Show.” Joan spots that banner, then throws a comrade’s motorcycle jacket over her OshKosh overalls, busts in, and parades down the runway. A mom onstage: “You’re ruining our event!” Joanie, grabbing the mike: “You’re ruining their lives! Sisters—you don’t have to do this!”

- Years later, on another tour, Joan hears the news from home: The paroled assassin of Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone has committed suicide. She and that same comrade buy a spraycan and paint “Dan White is Dead!” on freeway ramps in Boston.

She had many boyfriends, and then one: metal artist Dan Macchiarini. They settled down, bought a house when that was still possible, raised their daughter, Emma, and finally married—while step by step she made herself indispensable as a character actor, became an ace juggler, and developed a clown persona, Queenie Moon, whose red hair was even curlier than Joan’s and who quashed no impulse.

Clown and comic actress merged in her deadpan: She never telegraphed what was about to explode. She taught acting and circus and mentored younger clowns, with side stints as school bus driver, a shipyard welder, an electronics assembler, and a cabbie, to name a few. She joined a rowing club and did polar bear swims from Alcatraz with her husband and daughter. For Danny’s 50th birthday, she bought the family a trip to the Galapagos.

In the SFMT back then she was Joanie, since I was older and got there first. In The Independent Female, or A Man Has His Pride (1970), she played the ingenue heroine, who must choose between her junior executive fiancé, the supposed hero, and the “villain,” a feminist agitator. When radical feminists threatened to tear down our stage because we’d made the ingenue man-worshiping and silly, both Joans declared we’d played the role in life. The show was the troupe’s first as a collective; its success launched us.

In Counter Attack (Stagebridge, Oakland, 2012), she played a star waitress—the kind who can entertain a whole floor and stay in constant motion delivering flawless service to her tables. Pushing 70, this character defends her job against a younger rival at the price of alienating her own daughter. Juggling helped her learn to carry five loaded plates. Completing the circle, Sharon Lockwood, who would become another Bay Area go-to actor, played opposite Joan in 1970 and directed her in 2012.

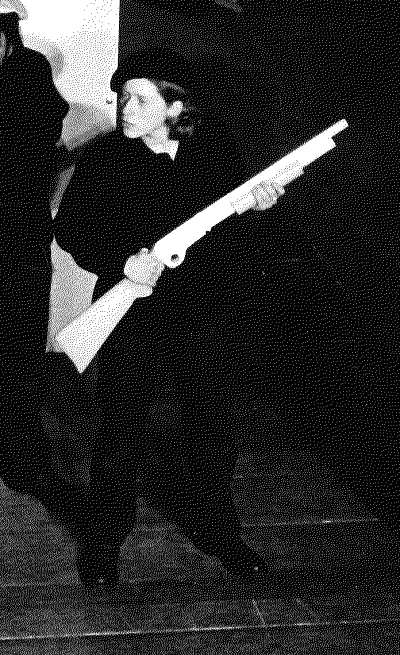

More standout leads in my Joanie memory show: Olga, a decayed ballerina who has waited 20 years for her sailor lover’s return but who still moves in pas-de-chat and tour jetés, in The Hotel Universe (1977). And Huey P. Newton: In 1970 a boyfriend of hers brought us a script about the Chicago Seven “conspiracy” trial, where the judge had Bobby Seale, cofounder of the Black Panther Party with Newton, bound and gagged. We gave it a parallel plot, the early history of the BPP. The SFMT was still all-white, and no white man could presume to play the charismatic leader, Huey. The solution: Joanie, barefaced in a black beret, cradling a wooden rifle, facing down white police signified by pig-like masks. “Ain’t you never heard of the 14th Amendment?”

Joan Mankin was a glutton for life, and made the most of it.

Joan Holden is a playwright based in the Bay Area.