In July, the Dramatists Guild of America and the Lilly Awards released “The Count,” a gender-based study of plays produced around the country in the last three years. It sampled 2,508 productions from 2011 to 2014 and found that female-written work made up just 22 percent of the plays being produced around the country.

American Theatre has been planning something similar for a couple of seasons now, using the exhaustive listings that TCG member theatres submit to us. Last season, we conducted an unofficial partial count and discovered that female playwrights made up 24 percent of the plays being produced that season. This season, we did a deeper, more complete dive into the schedules for data on playwrights’ representation by gender, providing a snapshot of what’s being produced in 2015–16. We did not duplicate “The Count” outright, but its methodology did provide some inspiration. Below are our findings.

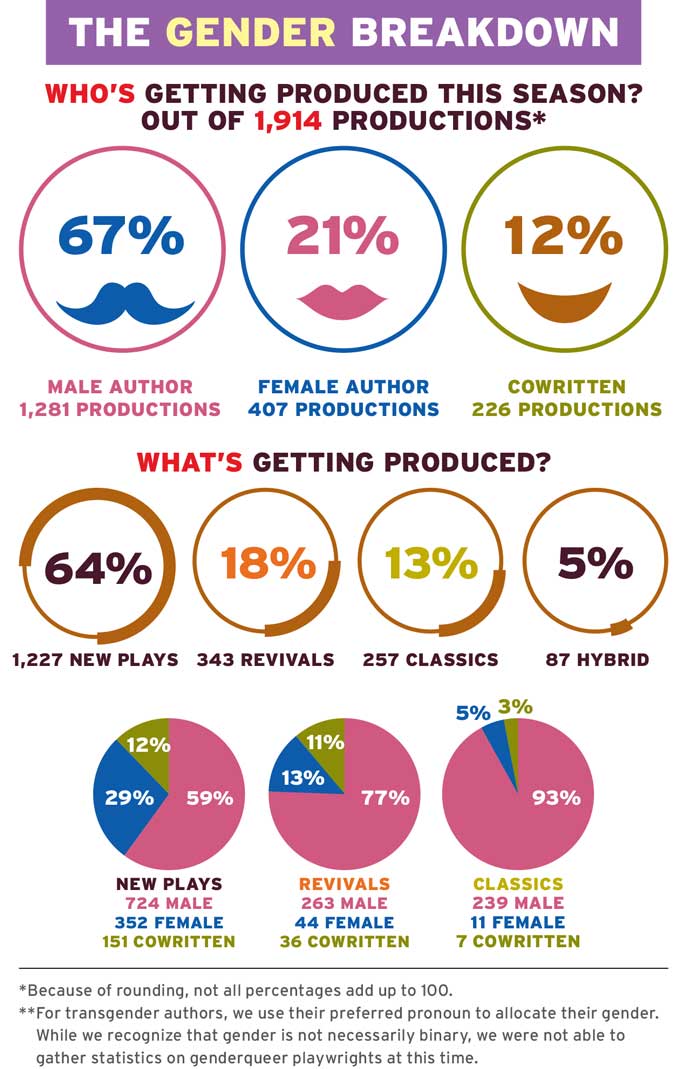

OUR METHODOLOGY: We counted each production in two categories: gender (male, female**) and era (new play, revival, classic). We considered plays that premiered between 2005 and now to be “new,” and a “revival” is defined as premiering between 1965 and 2004. Anything predating 1964 we’ve considered a canonical work, or a “classic.” We counted 1,914 productions at 363 theatres nationwide. To be eligible, productions need to be running between Sept. 1, 2015, to Aug. 31, 2016, with a minimum of a week’s worth of performances. We did not count improv shows, readings, cabarets, or most play festivals.

Some works in each category, gender and period, straddled these categories due to multiple authorship. In the case of gender, we considered any work written by multiple authors that included both men and women to be “cowritten,” a third subcategory under gender. It got a little more complicated for adaptations or translations of works, theatrical or otherwise. We included them in this third category if the gender of the original author and the adaptor diverged: For example, Annie Baker’s adaptation of Uncle Vanya would be considered cowritten by a man and woman, whereas, say, David Ives’s adaptation of Regnard’s The Heir Apparent would not be counted, for the purposes of our gender category, as cowritten.

Those two examples, though, would be counted across two periods in a subcategory we call “hybrid.” We divided them this way: For adaptations or translations of a theatrical work—such as Douglas Carter Beane’s reworked version of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella—we split authorship periods between the original and the adaptation. We made two exceptions to this rule: We did not consider adaptations of literary or filmic sources to be period-straddling in the same sense (that includes all those Christmas Carols). And we did not consider musical adaptations of any source material to be period-split, either (such as West Side Story). Our thinking was that significantly new pieces of theatre were created in the adaptation process.