One common snipe against Los Angeles is that it has no sense of history—that it’s a plastic boomtown that replaces buildings like old shoes and paves its very riverbeds. But as far as the last hundred years of art and design are concerned (obviously including the business of show), there’s hardly a city on earth that can claim a more far-reaching contribution.

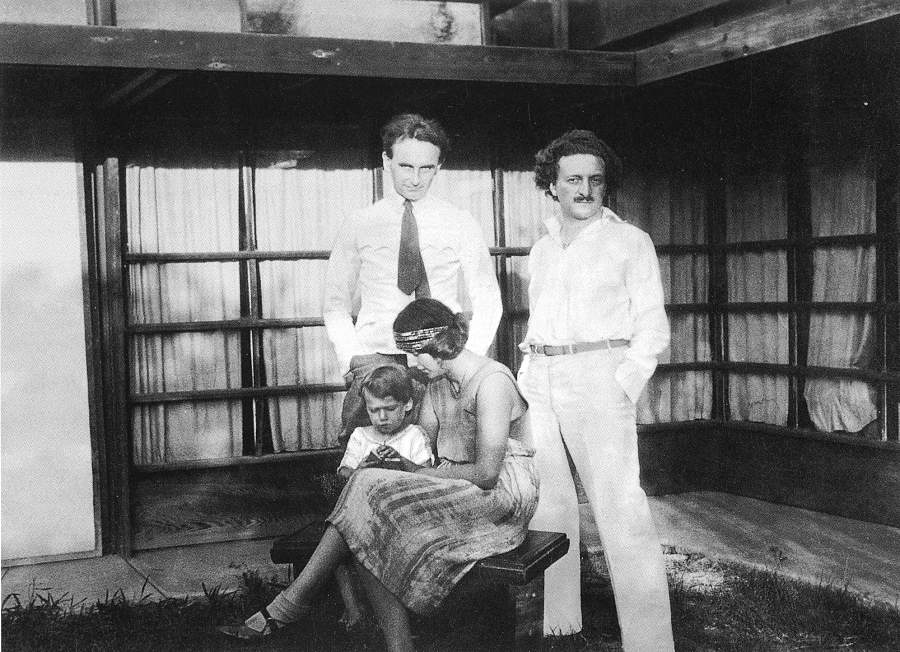

Case in point: Viennese-born Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra, two of the most influential modernist architects of the 20th Century, briefly worked as partners in the home their families shared in 1920s L.A. They’d known one another since their Austrian school days, when they eagerly attended coffeehouse lectures by the polemical design theorist Adolf Loos; both had also worked briefly for Frank Lloyd Wright. But after five years cohabiting and sharing studio space on West Hollywood’s Kings Road, they had a falling out, as creative geniuses will, and Neutra moved out. (The domicile, now best known simply as the Schindler House, has been preserved as a museum and architecture center.)

Neutra and Schindler would go on to create many private, public, and commercial properties throughout Southern California and elsewhere, putting L.A. on the permanent map of world design, though very much individually. Then, in 1953, decades after they parted in enmity, they ended up surprised to be sharing a randomly assigned L.A. hospital room.

What might have happened in that room is the subject of The Princes of Kings Road, a new play written and directed by Tom Lazarus under the auspices of Ensemble Studio Theatre/LA. Staged as a site-specific work in Neutra’s former studio, now called the Neutra Office Building, in Silver Lake, some seven miles from the Kings Road home. The play is a copresentation with one of the site’s current occupants, the Neutra Institute Museum of Silver Lake, where it will run Sept. 12–Oct. 4, with a cast of three: John Nielsen as Schindler, Ray Xifo as Neutra, and Heather Robinson as Nurse Rothstein.

One of the most consistently excellent small companies in Los Angeles, EST/LA, like Schindler and Neutra, is a West Coast offshoot of a parent aesthetic. New York’s Ensemble Studio Theatre, established in 1968 by the late Curt Dempster, still prides itself as a development body, producing several new plays per season. A wholly independent body that didn’t incorporate under formal nonprofit status until 2000, the 200-member EST/LA has been developing new works by emerging playwrights since 1979. Lazarus falls in this category despite a long career writing and directing for film and television; his first production for the company, Princes was nurtured and workshopped through EST/LA’s Playwrights Unit, moderated by Tom Baum under co-development artistic directors Sheena Metal and Keith Szarabajka.

Given the inherent drama of the Kings Road house, where the bohemian Schindlers and the straitlaced Neutras lived amid clashing cultures and wounded egos within the walls of an architectural masterpiece, to set a play about these architects anywhere else might seem counterintuitive. What’s more: two elderly men in a hospital room? How do you avoid a ton of exposition?

“When you’ve been writing for a long time, you learn to control what you’re writing—how to hide information,” Lazarus said during a recent visit to the Neutra Office Building. “I hate exposition, but it never occurred to me to to set the story in the Kings Road house. It would be too manipulative to cast younger actors so you could do flashbacks.”

He continued, “I became aware of the coincidence [of the former friends sharing a hospital room] through a documentary about the modernist photographer Julius Shulman. I thought, ‘What a moment.’ I wanted to invest it with emotion. Schindler feels Neutra has betrayed him; there’s all the heat of calling him a Judas.”

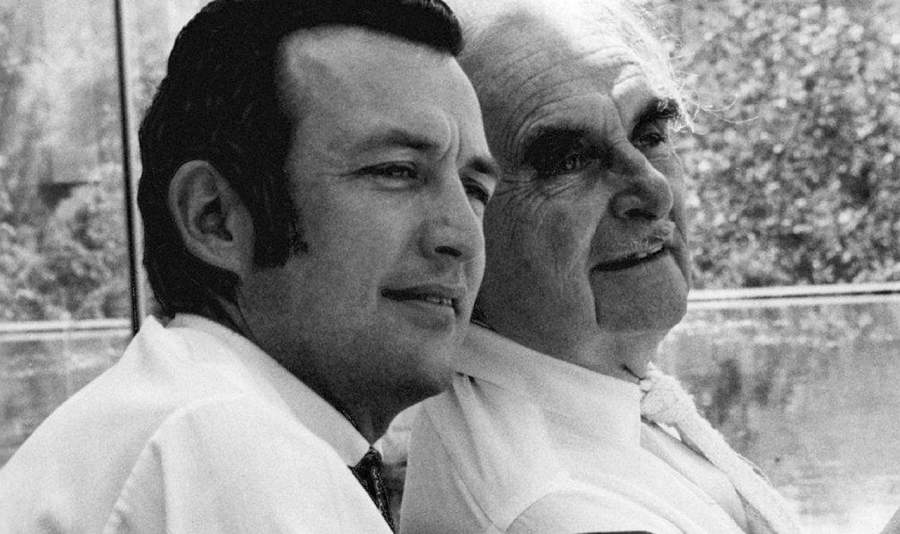

Dion Neutra, the architect’s son, was in the Cedars of Lebanon hospital room when the two giants looked at each other with bemused recognition. As an architect in his own right, Dion was father’s business partner for 30 years, and, since the elder Neutra’s death in 1970, a tireless advocate for his father’s legacy; a new edition of a book on his father’s never-built designs for the northwest corner of Hollywood and Vine is due out this year. Dion Neutra is still designing and building today.

Though he appreciates the artistic license necessary to adapting history into drama, he told me that the circumstances of the meeting were not quite as the play would have it.

“It’s not true that Schindler was antagonistic to my father,” he said. “He just looked up and said, ‘It’s you.'” It’s also not true, he said, that the two former colleagues “hadn’t spoken at all since the partnership.” Still, the playwright “is right that there was a separation of the ways, and of course there would be some residue from that.”

Built in 1950 and still hosting business tenants today, the Neutra Office Building is the only unaltered example of Neutra’s commercial properties still standing. Featuring exposed strip lighting, original acoustic ceiling tiles, and Neutra’s beloved louvers, the building’s spacious former drafting studio (now used as an art gallery) makes a fine host for the Princes set: evocative yet neutral enough to embrace another story and place, as well as between 50 and 60 seats.

This isn’t the first show to take advantage of the room. Lazarus said, “We’d been to a play at the Neutra Museum, Chalk Rep’s Uncle Vanya. It’s a very simple space. We don’t violate it, and the space doesn’t violate what we’re doing. It’s part of the cachet. It adds to the package—not to sound crass. Anything we can add to make it full and rich, we should.”

Princes is EST/LA’s first production since Gates McFadden resigned as artistic director last year, and Rod Menzies, who now shares the title of producing artistic director with Carole Real, admits that McFadden has been a tough act to follow. “There’s definitely a sense of a vacuum since Gates left,” he said. “Gates moved us into a new range in terms of how we were recognized for what we could do. But in some cases she was writing checks to make sure what got done.”

So, in a transitional moment for the company, why this play now?

“The fact that this is an L.A. story is compelling to us, in that it examines L.A.’s cultural legacy,” says Menzies. “I really appreciate the intellectual history here, the history of art. And this is not an exhibit—it’s a play, which makes it interesting from the perspective of a multi-disciplinary approach.”

Says Real, “I love the way Tom’s play speaks to the way rivalry and competition are both positive and negative forces. It does go into the past but in a way that’s very present.”

Of EST/LA’s future, Menzies said: “We have some grants, but they’re not infrastructure grants. It’s very demanding. My hunch is that in 10 years we’ll still be a strong company. But right now, we’re running an Indiegogo campaign for our current season.”

As The Princes of Kings Road reminds us, art never did come easy.