SAN FRANCISCO and WASHINGTON, D.C.: The nameless daughter of Herod II and Herodias in the New Testament is synonymous with seduction and vengeance: She danced before the king, requested the decollation of St. John the Baptist, and proudly displayed the head of the man who reproved her mother’s marriage on a platter. The world has given this biblical character a narrative and a name, linking her to a historical figure mentioned by Josephus, and her legend has spanned paintings, films, dramas, and opera through the ages.

Oscar Wilde embellished her myth with his 1891 play Salomé, turning her dance before her father, the king, into the iconic dance of the seven veils. Composer Richard Strauss later set the murderous story to a German libretto in 1905. Reimagined iterations of the story continue to inspire new adaptations (remember Al Pacino’s wild Wilde Salomé, which featured a young Jessica Chastain in the role?). Currently at the New Conservatory Theatre Center in San Francisco, burlesque performance artist trixxie carr‘s one-woman glam-rock musical, Salome, Dance for Me, puts it focus on the heroine’s trademark ecdysiastic dance. Yaël Farber’s Salomé, meanwhile, is an ensemble-based exploration of first-century Palestine with the mythical story at its center, set to open in October at the Shakespeare Theatre Company in Washington, D.C.

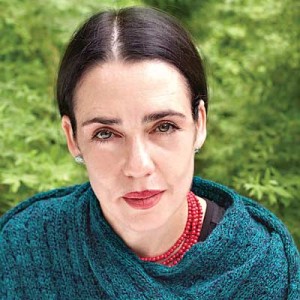

For both artists, the world’s fascination with Salomé invites further examination. “This seems to be coming up in the world’s consciousness,” said Farber. “I think there is a pendulum swing in how the feminine is regarded, and in how much farther we can go with a very limited idea of what the role of the feminine can play inside the events of the world,” said Farber.

“She wants to be heard!” exclaimed carr of the multiple productions. “We respected the story and took it to unexpected places that most people wouldn’t go.”

The two productions couldn’t be more different: Carr developed her reincarnation show over the course of a year as part of New Conservatory’s emerging artists program. She was first intrigued by Aubrey Beardsley’s black ink drawings of Salomé, which were included in a copy of Wilde’s play. Using musical themes from Strauss’s opera, carr experimented with different genres of music and finally landed on a glam-rock sound, with John the Baptist reconceived as a rock frontman (carr plays all the characters, including Herod, Iokanaan, and Herodias). With many source materials at hand, carr and her collaborators decided to hone in on Salome’s need to escape.

“It is that feeling of entrapment in one place, or one idea, or one feeling,” said carr. “Wilde took it and really ran with it—created a beautiful story out of this concept that was kind of nebulous, and he made a definitive piece of art,” said carr. Saying she’s bringing “a bit of a more modern take” to the tale, carr sees the legend as an ongoing historical project: “It is the link of storytelling, and I’m adding a chain onto it.”

For Farber, it’s about deconstructing the seductress narrative the world has built for Salomé.

“My work is often very politically focused, and that can form a deadly word in theatre, but I like to bring the charge of the politics around it,” said Farber, whose searing production of Mies Julie recast Strindberg’s classic in Farber’s native South Africa. Accordingly, her version is interested in examining Salomé’s role in John the Baptist’s death.

“It has been relegated to the idea of some kind of sexual longing, or the vengeance of her mother,” said Farber. “It is always about some kind of very primal, infantile response when it is related to women, as opposed to some potentially very strategic political choice.”

True to form, Farber is also using her South African background as a lens to view the story’s political implications.

“To mobilize a form of critical thinking, societies that tell us how to feel and what to think make atrocities against other human beings possible,” said Farber. “I think this functions in all our societies, but some societies are more extreme; I grew up in one of those more extreme societies.” The work of her Salomé, she said, is to look “at this story, set inside a very patriarchal paradigm, and return her to the center of her own narrative.”

In many interpretations of the story, including Strauss’s opera, Salomé’s provocative dance of the seven veils takes center stage as a sort of decadent climax. In Salome, Dance for Me, carr interprets the dance as a metaphor, with the veils representing layers of reality. In Farber’s Salomé, meanwhile, the dance that has defined the character is not a central event. “We don’t want to strip the power of that sensuality away, but the motivations behind it are often relegated to the domestic, and I am interested in looking at national concerns in the hands of a woman.”

Both reincarnations of the character aim to set this icon free—free from the constraints of her own unwitting actions, and free from socially imposed views of her story. For a nameless biblical character who changed the course of history, Salomé has come a long way and still has something new to say.