GREAT BARRINGTON, MASS.: Reports of the death of Brooklyn-based ensemble Radiohole have been greatly exaggerated. In September 2013, following a rent hike by their landlord, the group was forced to leave their Williamsburg rehearsal and performance space of 13 years, the Collapsable Hole. A funeral—more like a bacchanal—was held, complete with booze, songs, and some nudity. Then the question came: What is Radiohole without the Hole?

“When we lost the Collapsable Hole in 2013, we weren’t sure if we were going to be able to continue,” admits Radiohole cofounder Eric Dyer, in a three-way phone conversation with fellow founders Maggie Hoffman and Erin Douglass. “We thought it might be the death of the company.”

A little less than two years later, the company—which specializes in devised work with a technological edge and a grossout aesthetic—has birthed a new show. Tarzana, commissioned and presented by Mass Live Arts, has its world premiere this week (July 23–25).

To create the show Radiohole took what constitutes a new approach for them: They commissioned a text from Los Angeles–based playwright Jason Grote. No specifications were given, and what he turned in was a script combining Superman, Robespierre, and denizens of New York 1970s New Wave scene, trapped together inside the “bottle city of Kandor” (for you non-geeks, that’s the capital city of Superman’s home planet Krypton, stolen by the villain Brainiac and shrunken to fit inside a glass bottle). But what do those three elements have to say to each other?

“I think what those characters have in common is literally us,” says Dyer, without a note of irony. “I think it’s really about Radiohole as an ensemble being together—our performance style, our approach to the work, and our ability to take disparate elements and make them coexist onstage, with a little more than a relationship of textures and maybe themes.”

Blending, deconstructing, and otherwise messing around with well-known works has always been part of the company’s aesthetic. Inflatable Frankenstein (2013) brought together author Mary Shelley, her most famous work, and the theatre talkback for a meditation on the act of creation. And Whatever, Heaven Allows (2010) juxtaposed John Milton’s Paradise Lost with Douglas Sirk’s ripe 1955 melodrama All That Heaven Allows for a queasy celebration of earthly pleasures.

The notion of bringing an actual playwright into the teeming mix was born of both curiosity and necessity. When the Collapsible Hole was still open, the troupe could come and go as they pleased, allowing them to continually devise, revise, experiment, and workshop. But without an artistic home, Radiohole had to figure out a way of working that was less time-intensive.

“I think that whole commission was really a response to us feeling like we could be dead if we don’t figure out something new,” says Douglass. “When we got the play, we put our hands in a hat and picked out the character names, and that’s who we’re going to play. And we started reading it.” Douglass and Dyer, for instance, play a pair of blonde New Wave–era twins who spend a majority of the play lounging on the couch.

When you give a script to Radiohole, of course, you don’t expect them to stick to it verbatim. Grote’s script was just the foundation of their work, they say. The team—which along with Douglass, Dyer, and Hoffman includes Scott Halvorsen Gillette—went in and started trimming and moving things around.

The design is a collaborative effort, with the Kandor backdrop made up of hand-drawn, comic-book-like, black-and-white drawings and props made exclusively out of cardboard, painted black and white. Cardboard is a running theme: The twins played by Douglass and Dyer sit on a cardboard couch and smoke cardboard cigarettes, and pre-show cupcakes and milk will be served for free out of a cardboard ice cream cart. (Not to worry, longtime fans, free beer will also be offered, as always.)

As in previous works, all of the tech cues in Tarzana will be run onstage by the cast, using iPhones and, in a new twist, a Makey Makey touchpad made of cardboard and tin foil.

“When we were doing our work in progress, no one could remember which buttons on our phone went to which samples,” says Douglass. “So we had to draw ourselves a big cheat sheet, and that cheat sheet turned into the Makey Makey board that we’re now using.”

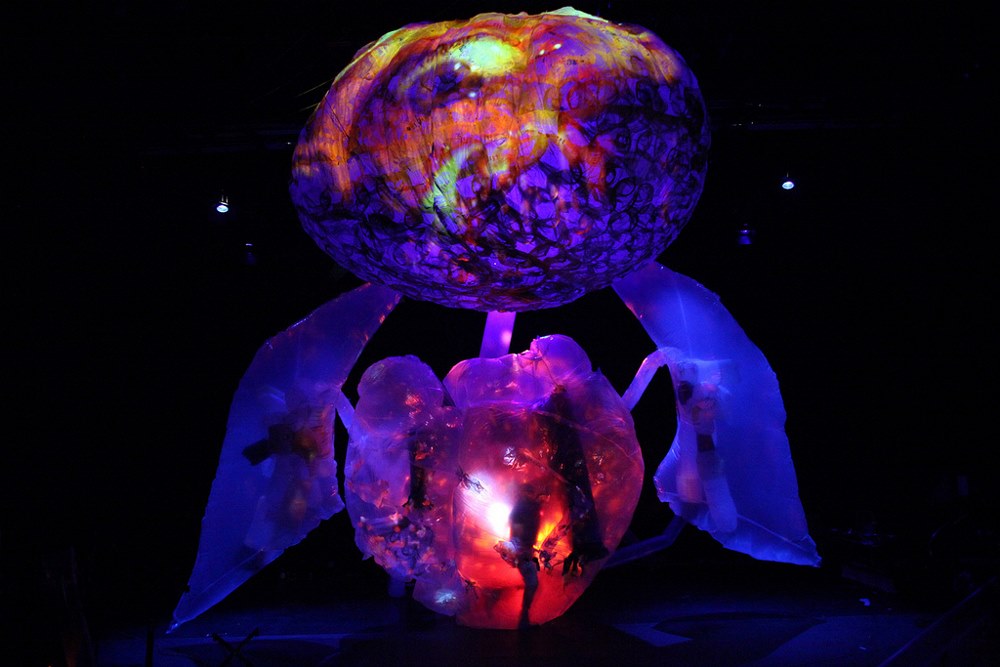

A mixture of sophisticated technology and cheap materials is nothing new for Radiohole. The closing image of Inflatable Frankenstein was a giant balloon of brains, hearts, and lungs, made out of plastic shopping bags, plastered with projected images, and filling up the entire theatre.

“It helps because it’s inexpensive. We can just find cardboard down the street,” says Hoffman, who plays Robespierre (pulling names out of a hat being a very reliable way to cast nontraditionally). But there is another reason: A Radiohole show is always messy. Very messy: Inflatable Frankenstein featured massive slabs of pink goo that slowly dripped down from ceiling to floor. Whatever, Heaven Allows had the cast perform while covered in chocolate pudding, and in one momentous scene, cherry Jell-o rained from the rafters. For Tarzana, the operative gross-out substance is blood—copious amounts of blood.

“In this show, everything gets destroyed by the blood every night, so we have to replace it and have all new stuff,” says Hoffman. Adds Douglass: “And we sort of get destroyed, because it stains our skin.”

The red splatters also add necessary color to the monochrome set and props. And it function as a reference to the blood, sweat, and tears that go into artistic creation. “For us, there were a lot of personal reasons to be thinking about death,” says Dyer.

Indeed, the Collapsable Hole may be extinct, and Radiohole’s budget may be smaller than it used to be. But, like a certain lab-created monster, Radiohole is very much alive.

“Every Radiohole show feels like the last Radiohole show,” says Hoffman. “Every time we’re dealing with our own possible death and all these issues of how we can continue.”