We in the word trade all have our style preferences and pet peeves, much as some of us may protest (too much, tellingly) that we’re not pedants or prisses about language. (A preference of mine, to give an example, is the gender-neutral singular “they”; a pet peeve would be “cliché” used as an adjective.) As a writer/editor since my high school newspaper days, I’ve had the chance to test, hone, and apply my usage tastes (right there was another one, the Oxford comma), and have composed and contributed to my share of “style” guides over the years.

The names of the magazines I’ve worked for have themselves posed and answered style questions of their own, starting with the Brophy Roundup (“roundup,” one word, no hyphen), the L.A. Downtown News (in whose copy the word “Downtown” was always capitalized—somewhat aspirationally, it seemed to me), and Back Stage West (confusing, since our style in the copy was resolutely “backstage”—a usage that Backstage has since adopted for its title).

Now I’m at a magazine whose name raises one of the longest-standing debates of English-language usage: American Theatre. If we’re “American,” the complaint goes, why do we spell “theatre” the British way?

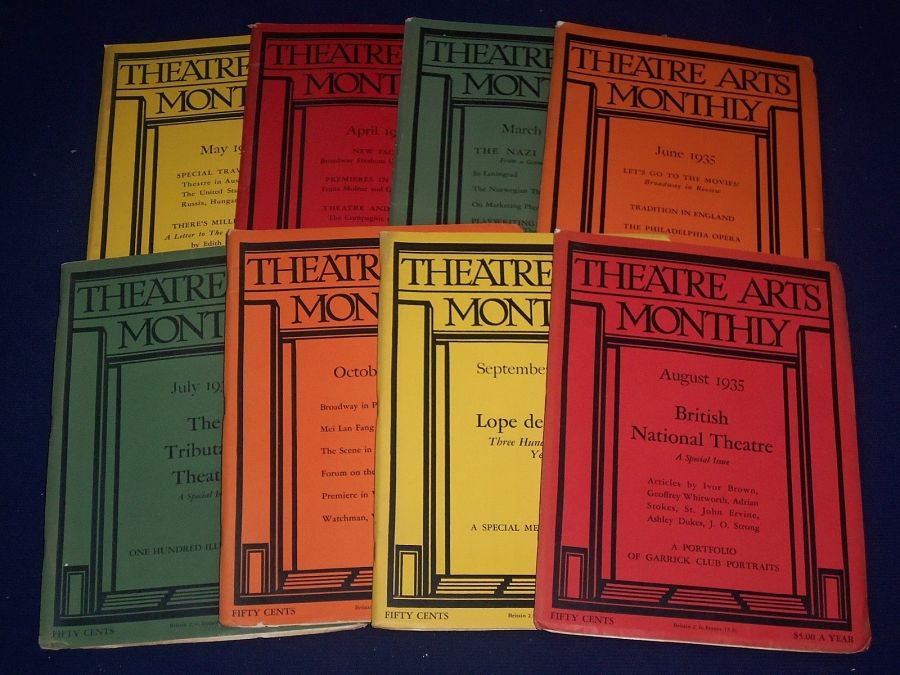

To start at the beginning: When Theatre Communications Group was founded, in 1961, “theatre” was the prevailing preference in the English-speaking world. Theatre Arts magazine, which published for half a century until shuttering in 1964, spelled it that way, as did most of the nation’s large resident theatres of either long standing or new vintage at the time: Guthrie Theatre, Goodman Theatre, Center Theatre Group. The Guthrie later changed its spelling to “theater,” and clearly the winds of change were blowing even then: Sampling a few mid-century New York Times reviews, we find that in 1949, the Gray Lady spelled it “theatre,” and still did so as late as 1957—but that by 1962, the “r” and “e” had been transposed.

Still, the Guthrie’s defection aside, if we’re reflecting our field, we should still prefer “theatre”: Of the 511 member theatres listed here, just 87 use the “theater” in their institutional name, with a whopping 242 continuing with “theatre,” and the remainder not including the word in their company’s name at all. (Note: Unlike the Times, which changes every spelling to “theater,” even in companies’ legal names, we strive to honor each organization’s individual spelling—I say “strive” because it’s easy to forget/hard to keep straight.)

As with any usage dispute, the impulse is to fight over which is “right.” But there is no end to this battle because there is no definitive answer. The difference in spelling is no more complicated than a bit of (arguably misplaced) trans-Atlantic deference. The etymology, if we must go there, is that “theatre” has been the accepted English spelling since roughly the 17th century, deriving from the French, in turn deriving from the Greek (“theatron”), while “theater” is a relatively recent American revival of an old Middle English spelling. The latter has been increasingly embraced in the U.S. in the last half-century or so as a kind of common-sensical populist alternative, as if to distinguish our indigenous American stage work from any vestigial European or Anglophilic associations. I remember someone intimating darkly to me that the “theater” spelling started to take hold around the time of Reagan. More recently, an artistic director contributing an op-ed insisted to me that spelling it “theater” was a “class issue.”

Etymologist Anatoly Liberman, whom I contacted about the dispute, gave some fuel to that last notion, writing: “In art and fashion many people want to show off, and the best way to show off is to use British variants, which look (like) French. Hence theatre and glamour, but not color, caliber or luster.” Fair enough; after all, if anyone is inclined to show off, who more than theatre people?

I also asked Liberman about a popular myth I hear repeated with puzzling frequency, though not by any editor I’ve ever known: that “theatre” refers to the art form and “theater” to the venue. Not only is there no etymological basis for this rather arbitrary distinction, it’s also not borne out empirically in usage. Noted Liberman: “People are apt to ascribe different meaning to variant spellings. Look up the word gray in the OED: Some artists, as you will discover, say that gray and grey designate different shades of this color. After all, it is our business to endow words with meanings.”

Touché. Liberman’s frosty closer: “In principle, the whole problem is not worth a broken farthing on the market day, and that is why people become so passionate while discussing it. But you cannot avoid it, and the choice is up to you.”

Indeed it is.