It’s never the wrong time for Molière, of course. But is it possible that our current era of DOGE and MAGA, of brazen corruption and camp Americana, is uniquely suited to the acerbic social satires of the 17th-century farceur who gave the world a veritable shooting gallery of schemers, hypocrites, and narcissists as colorful as they are contemptible?

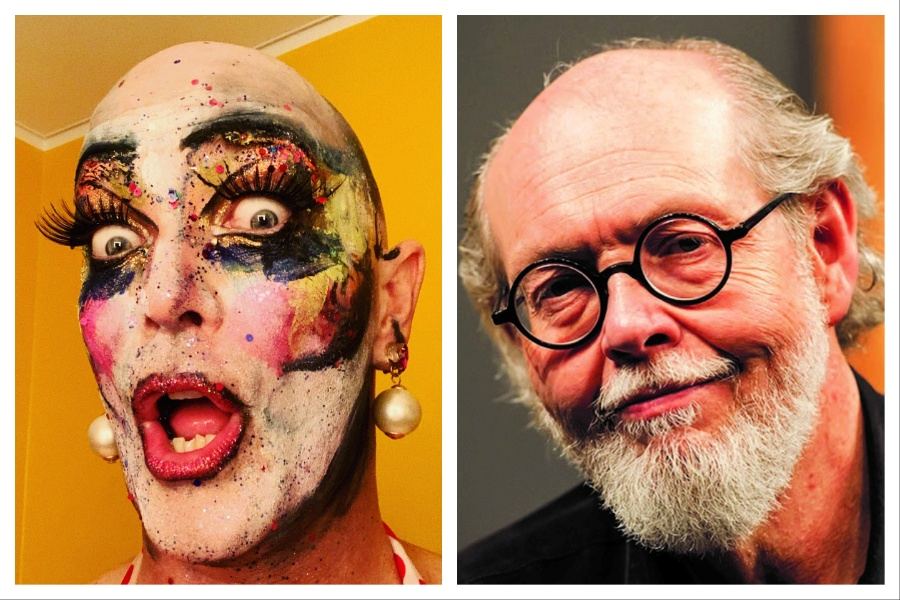

Two new productions in New York City take the spirit if not the letter of Molière as their guiding light. Taylor Mac’s Prosperous Fools, a deliciously savage takedown of arts philanthropy very loosely inspired by Molière’s Le Bourgeouis gentilhomme, starts previews at Brooklyn’s Theatre for a New Audience (TFANA) this Sunday, June 1, and runs there through June 29, in a staging starring Mac, directed by Darko Tresjnak. And Jeffrey Hatcher’s lean, knockabout adaptation of The Imaginary Invalid, now in previews, opens on June 2 and also runs through June 29 at Off-Broadway’s New World Stages, in a Red Bull Theater production headlined by Mark Linn-Baker and Sarah Stiles, and directed by Jesse Berger.

Both plays started as commissions of a sort: Years ago, Mac was approached about adapting Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, but judy (Mac’s pronoun) was more interested in penning a new contemporary take on its themes (a process that echoes the origin of Gary, which was inspired by a translation of Titus Andronicus judy undertook for Play On Shakespeare). And Hatcher, who’d previously adapted Gogol’s The Government Inspector and Jonson’s The Alchemist for Red Bull, was brought on board a few years ago to tailor an Invalid to the talents of Linn-Baker as Argan, the grasping hypochondriac of the play’s title.

I spoke to these two busy writers last week about enemas, philanthropy, and catharsis. The following has been edited for length and clarity.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: I want to start by asking about how much you’ve each kept from the Molière originals and what you’ve changed.

TAYLOR MAC: What Molière was doing in Le Bourgeous gentilhomme was making fun of someone with new money for the entertainment of the king. I was more interested in making fun of the king for the sake of the common person. I don’t have a patron who is the king, right? I’m an American, and we don’t have funding from our government, clearly. So who do I get funding from? It’s from oligarchs and patrons, people like Bloomberg, who don’t necessarily understand culture. And how do you accept their funding and yet critique them at the same time? That’s what I was interested in. Because our system is very similar to what Molière was dealing with, but incredibly different at the same time.

JEFFREY HATCHER: The Imaginary Invalid is a satire of the medical profession, but it’s very specific to the 17th century, and it’s very, very anti-doctor. Where we are now, at least on one side of the political divide, we’re very pro-doctor. In the original there’s a very lengthy discussion about, “Oh, don’t listen to doctors, just go about your life and you’ll be fine.” I was like: not really. Occasionally it’s nice to get a jab from somebody! But I do think the play is mostly about the way we see ourselves at the center of the universe. It’s about loneliness too—about how much people depend on the medical profession to provide the sort of things that friends and family used to. That’s our major thrust. That, and we want to be funny.

TAYLOR: I think that’s what Molière inspires: You want to be funny, but funny with a little teeth.

JEFFREY: Yeah, you want some sting. I mean, in Tartuffe, you get to the ending and suddenly it’s, “Oh, everything’s fine, the king is going to put this all right.” You can tell when Molière had to censor himself. Of course, with Imaginary Invalid, he died while he was doing the show. That’s the greatest form of self-censorship.

I’ve read about a John Wood adaptation where Argan dies at the end—he has a heart attack while the others onstage are celebrating.

JEFFREY: I haven’t seen that. I don’t think it’s a spoiler to say that Argan does not die in our production, although that would be funny. There’s nothing funnier than a heart attack onstage.

I wonder to what extent you feel you’re aiming your plays’ satire at our current moment.

TAYLOR: Well, I wrote it 12 years ago. But it feels like I wrote it yesterday, because all that’s happened in the last 12 years has just gotten more intense. To some degree, what my play is is a cathartic expressing of all the things people have whispered to me in 32 years of attending galas and financing things and shaking hands at donor events and dealing with artistic directors who are compromising and asking you to censor yourself. All the things that people won’t say publicly, I put into one play. So in some ways, I haven’t actually written it; I’ve just been taking notes for 32 years.

JEFFREY: Is it contemporary, set in 2025?

TAYLOR: Yeah, it’s set at a gala for a contemporary ballet. It’s the opening night performance of a new ballet they’re also using as their gala, where they’re honoring somebody like the Sackler family, and also somebody like Audrey Hepburn, a humanitarian star. You know, at galas, they like to honor two people

JEFFREY: So, like Jean Hersholt and Himmler. It balances out.

TAYLOR: What I have found at galas is that they’ll honor somebody they actually respect, and then they’ll honor somebody that is the money, but even the person they actually respect is in a very compromised, hypocritical situation. So it’s all about our own hypocrisies. I make fun of the intern as much as I make fun of the artist, as much as I make fun of the oligarch. I mean, I clearly have a bull’s-eye on the oligarch. But we’re all grappling with how to deal with this feudal system of funding in what we pretend to be a democracy. How do we deal with that in the most ethical way? I don’t know, but it’s definitely worthy of a play.

Jeffrey, one thing you’ve definitely done is cut the original play.

JEFFREY: I mean, I don’t know about Taylor’s show, but I believe in the 75-minute play, like Oh, Mary! and Six. The original is in three acts and has three major musical bits. We’ve got some musical bits too, but they’re more contemporary vaudeville and very streamlined. We’ve taken the accordion and squeezed it, but I think the essential ideas of the play are still there. I think we were able to keep all the essentials and still get you out at 8:45.

Jeffrey, your version felt very—and I mean this as a compliment—one-liner-ized. You’v added jokes that are sort of embroidered on Molière’s situations; they aren’t exactly up-to-the-minute contemporary but they have a contemporary rhythm.

JEFFREY: My feeling is, you’d don’t set it in 1660 and then immediately start doing verbal references that are outside that time. So I think it may be straddling both things. I didn’t want it to be in a world where you could get an EKG or an X-ray. But I did want it to be a world where somebody has thought up what health insurance might look like in the future. I guess I would call it the Duck Soup approach.

In the original, Jeffrey, they refer to injections, but it’s all enemas in your play.

JEFFREY: Well, they say injections, but that’s what they meant.

TAYLOR: Right, when was the hypodermic needle even invented?

JEFFREY: I think that pops up maybe another 150 years later. But they really loved their enemas. I’ve seen productions of Imaginary Invalid where the enema stuff goes on for, it seems, hours.

TAYLOR: In terms of their knowledge of medicine at that time, the modern-day parallels would be more like New Age philosophies of medicine, like, “Take this herb, it’ll solve all your problems.”

JEFFREY: Yeah, we’ve got a couple of Gwyneth Paltrow Goop kinds of things in the play too: If you scrape up some mud and put it in a jar and say it’s 14 francs, now it’s worth something.

Jeffrey, you mentioned vaudeville earlier, and I was thinking about how Molière basically invented the form of the comédie-ballet, with dances and musical numbers between scenes, or vice versa.

JEFFREY: There’s that old Bernard Shaw quote: If you want to teach an audience a lesson, better make them laugh or they’ll kill you. I think that music is part of that; if you are putting in some claws or some fangs, then it’s nice to bring in the music to lift it up a bit, because the audience doesn’t really want to sit there for an hour and a half of bile, right? I think Molière was able to get away with a lot of stuff because he added the ballets and the singing and all that.

TAYLOR: I say that my play is a Juvenalian satire longing to be a comédie-ballet. It so wants to be that, but it just can’t help itself. It’s been so pent up censoring itself for 32 years that it has to be a satire.

Taylor, there is a line in the original Bourgeois gentilhomme where the music master imagines that if only the world could learn harmony from music, it would be a more harmonious place. Do you feel that art can change the world that way?

TAYLOR: I think creativity is needed for resistance right now. I don’t think our plays are going to stop the rise of fascism from happening in this moment, because it takes too long to get a play produced, and there are all these things in the way. But theatre artists are really creative. We have very special skills, and the activist community needs that kind of ACT UP-level creativity to do direct action. Die-ins aren’t going to end fascism, but if you could put a giant condom over a senator’s house to get visibility for AIDS when everyone was saying it didn’t exist—there are really inventive ways to do direct action that changes the world. I do believe in that, but I don’t think that that is the same thing as a play.

Like Molière’s characters, Taylor, yours seem to believe that if they could just get the oligarch to understand the arts, they’ll be fine. I think a lot of rich folks understand the arts just fine, but isn’t the real problem that they don’t really care, or they care about other things more?

TAYLOR: I don’t think they do understand the arts. Most of the philanthropists and board members I’ve encountered think nonprofits should run like a business. They don’t agree with artists who believe that nonprofits should lose money. I think they believe in the free market; they might be generous, but they think of philanthropy as moral. I’m not sure I’m on the same page. We claim to be a democracy, and yet our entire culture is built on a feudal system of somebody being able to give money, and that alleviates their guilt from hoarding all the money in the first place. It’s either commercial or feudal; those are the two options.

You have a good line about that: “Generosity is an impulse buy of morality.”

TAYLOR: Right, like buying a candy bar at the checkout line.

JEFFREY: I know people who are involved in nonprofits who don’t understand the notion of a nonprofit. They don’t understand why you wouldn’t want to make a profit. There is the ego aspect too. Would people donate $250,000 to a ballet company if their name wasn’t on the donor list?

TAYLOR: Exactly. And they give to success, not to need, so everyone has to pretend like they’re succeeding. But art isn’t always about success. So it’s an interesting conundrum we’re all in. Maybe billionaires shouldn’t decide what is seen; maybe we should make a culture of the people, for the people, by the people.

Both of these adaptations were written for an actor: in your case, Taylor, for yourself, and Jeffrey, for Mark Linn-Baker. Could you talk a little bit about the joys and challenges of writing for a performer, of having their voice and abilities in mind as you write?

JEFFREY: I know Mark’s rhythms, I know Mark’s texture. Something important about Imaginary Invalid is that I’ve seen lots of productions where Argan is a really unpleasant guy. It’s true, he does some unpleasant things; he tries to marry his daughter to a doctor so that he can have free healthcare for the rest of his life. But if you cast somebody like Mark, who’s a very warm presence and so is already very simpatico with the audience, then you’re able to get away with a lot more. You lose some of the bitterness that I sometimes think infects Molière, where everybody is so dark and nasty that it’s hard to enjoy them. With Mark, it’s been a joy. He’s a great farceur; he’s good verbally, good physically. And the audience actually wants to root for him. They want him to stay alive. They want him to be better.

And Taylor, you’ve built a lot of shows around yourself. Can you talk about that process?

TAYLOR: I mean, I didn’t write this part for myself, but it was a natural fit. I’ve always liked to write roles for myself. Nobody else casts me, so I might as well! But that’s part of the fun, and it’s what Molière did too. I think it’s just a hoot to act in your own plays.

JEFFREY: There’s also the advantage that you’ve already heard the line in your head, and you don’t have to wrestle with an actor and a director to convince somebody to say it right.

TAYLOR: Yeah, but at the same time, sometimes the pace you write in and hear it in your head isn’t reasonable for an audience. So you do need your own process to slow down and learn how to communicate the words. Because I understand what everything means, that doesn’t necessarily mean the audience does. And I think there’s an assumption that, because you wrote the play, how you are on day one is how you’re going to be for the rest of the experience. No; I need to learn too.

Another problem is, I come in with my nerves on the first day, so I’m speeding a little bit, and all the actors take that as a cue that they’re supposed to go really fast or really big. There’s always a juggling routine of saying: Let’s treat this like we found this play from the 16th century and we’re all in the room figuring it out together, even though, yes, I’m the playwright. People downtown don’t seem to have a problem with it, but in the more professional, Off-Broadway level of theatre, they really freak out when the playwright’s in the room, in my experience.

Jeffrey, do you terrify people in the rehearsal room?

Oh yes, I’m a terrifying presence. [Laughter] Actually, it kind of helps when you’re doing an adaptation, because if somebody compliments you, you can say, “Thank you,” and if they say, “I don’t think this quite works,” you say, “Ah, Molière.”

TAYLOR: Right—it’s his fault!

What has been the most challenging or toughest thing about this process, and how have you met it?

TAYLOR: So many, many, many things. But the one I think of is allowing myself to go Juvenal. Molière sometimes can be aggressive and bitter and mean-spirited, and I have a tendency to want to soften that. It’s all right to soften it; you know, every tragedy could have some comedy at the end of it, and vice versa, just so you understand the context. I do that in the play, for sure. But I was also like: But can I go there? That was a challenge.

It’s also very challenging to write a play that is critical of the people who are funding your play—how to communicate that in a responsible way, but also a clear and honest way, while not diminishing or allowing the money to control how it’s told. So I went to a place where nobody who has money is in charge of it. So I’m proud of that, whether or not it means I’ll never work again. That’s another conversation.

Jeffrey, what was hardest for you?

JEFFREY: I suppose it’s what I mentioned before—that the original play basically pooh-poohs doctors and says, “Just go out and take a walk.” Again, we don’t live in that context. So fiddling with some of that was a little bit difficult, but not much. I guess the worst of it is people who come up to you and say, “Oh, you’re doing the Imaginary Invalid? I bet you’ve got a lot of RFK Jr. jokes!” You know, we’ve got The Daily Show, we’ve got SNL; I’ve got nothing to add to that onslaught. So when people say, “Oh, I bet you’ll do this,” I tend to pull back from that. I don’t want to do what everybody expects us to do.

TAYLOR: I had that issue with my play. You know, Trump and Musk aren’t philanthropists in any way, shape, or form, and David Koch isn’t a smidgen as crass as the character I created. But there is some kind of juggling and hybridity among them all in the character that I made. So there is this assumption that, “Oh, you’re doing a play with an oligarch in it, is it going to take down Musk?” My feeling is, it’s all there without having to do any kind of impersonation. It’s just present. And it’s really cathartic to experience that through a play rather than through a late-night show or a meme or a complaint with your friends or a TikTok video. It’s cathartic to experience these extreme things we’re dealing with through the lineage and the lens of Molière. All this history and all these tropes we’ve been dealing with our entire lives—it’s just fun to play in that sandbox of catharsis. Every time I watch the ending of our play, I’m just so happy for it. It feels like a release from this tension.

JEFFREY: Well, there’s a reason these plays have existed for 300, 400 years. And we have to remember that our audiences bring their own experience to the show, so there are things we don’t have to do, because they already know it. All they need to do is encounter the character and the situation, and immediately they’ll start thinking about Trump or Musk or RFK Jr. We don’t have to do it for them.

Is there anything I didn’t ask about that you want to add?

JEFFREY: I’m terrified of my doctor. Any time I’ve got a problem, and I sit down and try to explain it to him, I see a bubble over his head that says, “I wish this asshole would leave my room.”

TAYLOR: That is how I feel every time.

JEFFREY: Someday I’m gonna die and it’s finally gonna be: “See, I was sick and you didn’t believe me.” That’ll be on my gravestone.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.

Related

TFANA Names Arin Arbus Artistic Director

The company’s former associate artistic director will step up when founding artistic director Jeffrey Horowitz departs in August.

In "Entrances & Exits"

Parson’s Nose Theater Announces 2015–16 Season

Themes of belief and family unite selections from the Southern California--based theatre's 16th season.

In "Seasons"

Theatre for a New Audience Announces 2016-17 Season

The lineup features works by Thornton Wilder, Samuel Beckett, Shakespeare, and more.

In "Mid Atlantic"