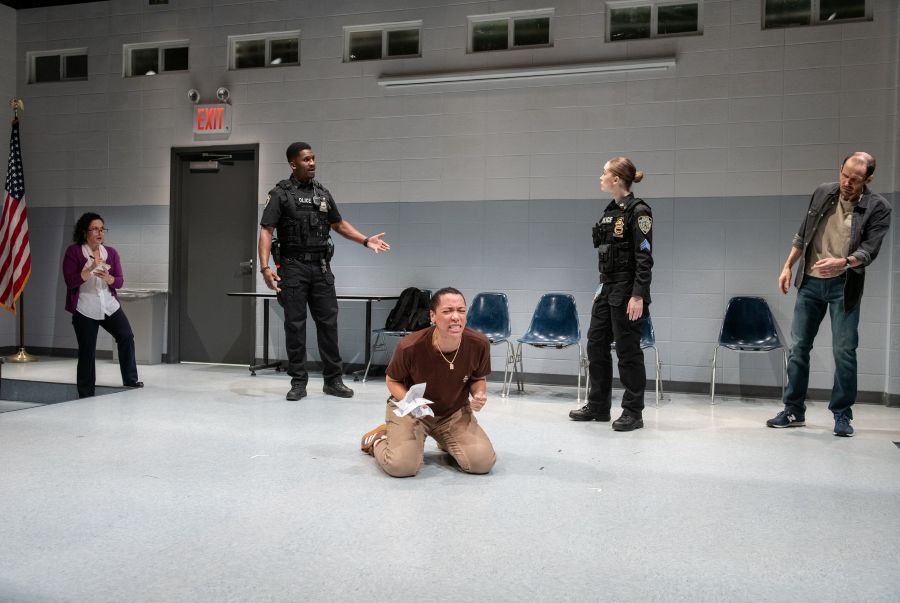

On a recent trip to Washington, D.C., I had the pleasure of seeing four new plays. My long weekend started on a Thursday with Karen Zacarías’s adaptation of Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence at Arena Stage, directed by artistic director Hana S. Sharif. This lavish manners play regaled the audience with elaborate costumes and juicy tête-à-têtes for more than three hours. Then, on Friday, I headed to the Studio Theatre for The Scenarios, an arresting new play by Matthew Capodicasa about actors who work in a police training program. If Capodicasa’s intention was to affect the audience by making the scenarios feel real, he succeeded.

That Saturday, I took in A Room in the Castle by Lauren Gunderson at Folger Shakespeare, a funny, endearing take on Hamlet from the women’s point of view. Lastly, I saw FlawBored’s It’s A Motherf***ing Pleasure at Woolly Mammoth, a metatheatrical romp about how attempts to be politically correct can go awry in the most absurd ways.

After this long weekend of seeing four very different plays at four unique theatres, the word that hung in my mind was diversity. So many people have talked, trained, cried, pushed, borrowed, and begged for the theatre to be a place of multitudes. That is why the sociopolitical tumult of the current moment is especially piercing. The federal government has eliminated its diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) programs, and is pressing states and private entities to do the same.

Book bans continue, with a hyperfocus on titles by Black women and LGBTQIA+ authors. Theatre Communications Group and four theatres that joined an ACLU lawsuit contesting the new National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) grant application requirements around gender expression and gender discrimination were not granted preliminary relief by a federal judge. Artists and arts institutions have seen federal grants snatched from programs for everything from training public school teachers to improving healthcare delivery. The quickness and ease with which this undoing is happening is alarming, but I can’t say it’s surprising.

I can’t escape the feeling that we are living in the consequences of politicizing and commodifying humanistic values. A decade ago, the buzzwords were all about making the business case for diversity. Theatre leaders and artists were told repeatedly that if they could prove that diversifying staff and programming had a positive impact on the bottom line and put butts in seats, it would become a part of the way we operate. People went about the business of making the case for more than a decade, implementing development and marketing initiatives so that artists and audiences could become more reflective of U.S. demographics.

In the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matters demonstrations, several theatres drafted diversity statements and funders created grants for the purpose of leveling the playing field. As the protests spread across the world, funds that were said not to have existed magically appeared. Anything to get people back in the house. Plus, it helped that the business case was shouted even louder: Look at the population trends and how much money you’re leaving on the table, the thinking went. New-play development programs, commissions, residencies, fellowships, and full-time positions became available for artists of color who were positioned to win.

It’s a scary day in America when 501c3 organizations are questioning whether fighting for humanity is a line item in their budgets.

Of course, not everyone was on board with the idea of removing the gatekeepers. The statement “Go woke, go broke” echoed in watercooler conversations and in mainstream media coverage about DEI initiatives, and the theatre was no exception. And yes, some theatres did lose money on new audience acquisition, but in many cases the business case for diversity was borne out. New plays and musicals written by playwrights of color met or set box office records at regional theatres. In the commercial theatre, look at any top 10 or top 20 list of top-grossing Broadway shows and at least half feature people of color in lead roles.

As I think about the slate of plays I watched in D.C., I think about how private and public funding, coupled with increased attention on DEI, made it possible for these shows to (a) exist and (b) have different and necessary conversations with myriad audiences.

Now the tides have turned. DEI is out of political and social favor and public and private institutions are pulling back dollars and commitments. The business case was made—but now the goal post has moved. One can only logically conclude that it was never about money. It is about who is seen as worthy of the opportunity to achieve that ever-fleeting American dream.

Discrimination has always been expensive; imagine having to construct four sets of bathrooms and two sets of water fountains and two different sets of pipes for all of it. That was America before 1964. Whining about balance sheets is a distraction from holding people accountable to their own integrity. There is and has always been plenty of money; it’s just a matter of who’s holding it.

The fundamental flaw was tying DEI—read humanistic value and inherent worthiness and being—to budget lines in the first place. In the theatre, this fixation on budgets feels like the antithesis of what the inventors of this art form intended centuries ago; fighting the tyranny of the bottom line it was certainly an aching concern of the founders of the regional theatre movement. It’s a scary day in America when 501c3 organizations are questioning whether fighting for humanity is a line item in their budgets. Our commitment to welcoming everyone in the American theatre can’t be subjected to grant cycles. We must think beyond trends and fickle funding.

What women, people of color, immigrants, refugees, LGBTQIA+, and people who live at those intersections are being told to do right now is go back into hiding. But it’s hard for people to go back to being invisible and closeted once they’ve gotten a taste of acceptance, or at the very least teeth-grinding tolerance. I’m reminded of that scene from season two of the Hulu series Ramy in which Ramy’s sister Dena is told by a tow truck driver, “It’s a melting pot, so fucking melt!” But you don’t get cardamom, coriander, cayenne, cumin, and curry if everyone just melts.

We don’t get a glorious theatre weekend like the one I saw in D.C., with multicultural casts and audiences that reflect the demographics of our cities, without inviting everyone to the party. When scarcity meets artmaking in the nonprofit theatre, people who are othered always get pushed to the margins. This is the pattern. I want to believe there will be a critical mass around resistance, but, to quote Sister Aloysius, “I have doubts.”

I need artists and the institutions that employ them not to melt. When people who have been historically excluded from the arts and media finally see themselves represented in a way that resonates with their lived experiences, there’s a sense of belonging that lifts everyone. The American theatre at its best is a sanctuary and beacon of light, which we all desperately need right now. What is seen cannot be unseen. My highest hope for the theatre is that when the keepers try to resume their positions, they find that there are no gates.

Kelundra Smith is TCG’s publications director, guiding strategy for TCG Books, ARTSEARCH, and American Theatre magazine.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.