Following are edited excerpts from Garrett Eisler’s new book, Ben Hecht’s Theatre of Jewish Protest, a history and anthology of dramatic writings about the Holocaust by the playwright and screenwriter best known for The Front Page, His Girl Friday, Notorious, and Scarface. Eisler’s book is available now from Rutgers University Press.

There are two internationally recognized “remembrance days” mourning the victims of the Holocaust. The United Nations has chosen the date of Jan. 27 as an International Holocaust Remembrance Day to mark the anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1945. But in 1951, the State of Israel declared the 27th day of the Hebrew calendar month of Nisan (the first month of spring) a “Holocaust and Heroism Remembrance Day,” commemorating not only the suffering of the Shoah overall, but specifically the occasion of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in the spring of 1943 (April 19-May 16), when captive Jews attempted an armed insurgency against their German occupiers, engaging them in combat for nearly a month. While they could not ultimately liberate themselves, word travelled fast around the world of their heroic resistance.

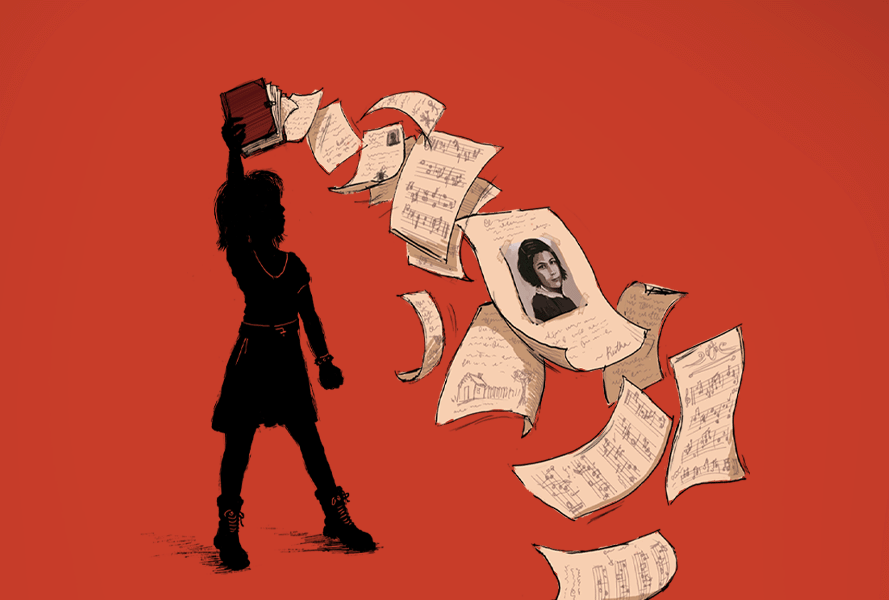

By that July, in fact, the uprising was already being dramatized on the American stage—as part of Ben Hecht’s mass pageant We Will Never Die, a “Memorial Dedicated to the Two Million Jewish Dead of Europe” that toured the country during the spring and summer of 1943. At a moment when the genocide of European Jews was already underway but still generally unknown to the American public, Hecht and Broadway producer extraordinaire Billy Rose joined forces with an upstart Zionist group (the Committee for a Jewish Army of Stateless and Palestinian Jews) to produce a mass spectacle they hoped would attract enough media attention to bring the issue to the fore amid an already overwhelming daily diet of war news from abroad.

The premiere of We Will Never Die at New York’s Madison Square Garden on March 9, 1943, did succeed in garnering headlines as well as sold-out crowds of 17,000 for each of its two performances that night. Hecht’s respected status in Broadway and Hollywood circles drew the participation of other show business luminaries, including Moss Hart, who directed, and Kurt Weill, who provided an ambitious symphonic score. The premiere’s success was in no small part due to a cast headlined by two of Hollywood’s greatest stars, Paul Muni and Edward G. Robinson. Other celebrities appeared in performances on the pageant’s tour throughout that spring, with performances in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Chicago, and Boston.

Originally, We Will Never Die had consisted of three main episodes: a “Roll Call” celebrating the contributions of notable Jewish thinkers, scientists, and artists to Western Civilization; a tribute to “Jews in the War,” Jewish soldiers fighting overseas in the armies of the U.S. and its allies; and “Remember Us,” a testimonial litany of Nazi war crimes recited by the spirits of the dead Jewish victims. But when Hecht heard about what was happening in Warsaw, he quickly wrote a new scene just in time for the final performance at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles on July 21, 1943. The pageant was already as topical and timely as a piece of theatre can be, but the events in Warsaw were literally “straight from the headlines.”

The resulting scene, “The Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto,” provided one element that had been missing from both Hecht’s script and much early coverage of the Holocaust itself: the efforts of oppressed Jewish civilians in occupied Europe to fight back against their Nazi persecutors. Many Holocaust dramatizations, then and now, can leave audiences with the impression that Jews were merely passive victims in their own mass slaughter. Hecht was determined that We Will Never Die not just show suffering, but also portray Jews actively resisting and demonstrating agency. In the events of the Warsaw Ghetto, Hecht—an old-school Chicago beat reporter who co-wrote that eternal dramatization of tabloid journalism The Front Page—knew an “underdog as hero” story when he saw it.

As a mass spectacle that played in stadium-size venues, We Will Never Die relied on spoken narration and nearly 1,000 extras to communicate the story of Hitler’s war on the Jewish people in a highly representational style. Accordingly, “The Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto,” like the pageant’s other episodes, engaged the audience more in bold images, dynamic music and sound, and heightened oratory than in individual character dialogue and development. For the Warsaw scene in particular, Hecht (one of Hollywood’s most prolific screenwriters) took a patently cinematic approach, creating an opening stage image akin to a movie “fade-in.” The script’s stage directions describe a 10-foot high slab representing the “ghetto wall of Warsaw,” as a crowd of supernumeraries representing the Jewish inhabitants enact a series of wordless scenes, while onstage narrators at microphones begin to tell the story of the revolt. We see the resistance fighters secretly prepare for battle as “four men pass through the crowd in the street, bearing a coffin” that we soon discover conceals the guns they will use. Later, recorded sound effects signal the approach of German tanks, and the stage action escalates as “groups of 20 and 30 men and women, carrying various arms, run through the street, shouting and waving their guns” and “fires light up the city beyond the wall.” For a scene written specifically for performance at the Hollywood Bowl, located at the heart of the “film colony,” Hecht’s mise-en-scène dramaturgy must have seemed especially apt.

The cinematic feel of the scene was reinforced by musical underscoring from one of Hollywood’s leading composers, Franz Waxman, himself a German Jewish refugee. (Kurt Weill, who had scored the rest of the pageant, was busy in New York writing his next musical, One Touch of Venus.) As part of his original score for the Warsaw scene, Waxman even wrote (in collaboration with a pre-Guys and Dolls Frank Loesser) a special “Battle Song” for the ghetto fighters. The song echoed similar instances in a popular Hollywood genre of the time, the European Resistance drama, typified by 1943’s Hangmen Also Die (which featured Bertolt Brecht’s sole American screenwriting credit) and 1942’s Casablanca. The spirit of Casablanca particularly infused the Warsaw scene, since Hecht cast as the lead narrator Paul Henreid, the actor who had played that film’s French resistance hero Victor Laszlo.

Movie influences aside, “The Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto” also bore the theatrical DNA of 1930s left-wing political theatre. (Some may find this ironic, since the Zionist group Hecht partnered with in producing the pageant was a front for the Irgun resistance army—the “Jewish terrorists” of British-ruled Palestine—which later spawned the more right-wing parties in Israeli politics. But that is just one of Hecht’s many contradictions.) On one level, the scene channels the “Living Newspaper” productions of the Federal Theatre Project in its deployment of “actualities” (reportage and found text), as well as in its reliance upon recorded sound effects, voiceover narration, and direct-address commentary. At one point, the words of Joseph Goebbels are heard over a loudspeaker, pronouncing, “The extermination of the Jewish race is of historic importance.” At the battle’s end, Hecht interpolates the verbatim text of the ghetto’s final radio dispatches: “Death sentence has been proclaimed on the last 35,000 Jews in Warsaw….Help us.”

Given how little was known publicly about the details of the evolving “Final Solution” then being executed by the Nazi war machine, the documentary-style conveyance of information was especially important. At one point, the narrator lists the names of some of the known concentration camps where Jews were being liquidated, including Auschwitz. Though Hecht uses the original Polish name of the town, “Oświęcim,” it is notable that when the pageant aired live on Los Angeles station KFWB, this moment was probably one of the first references to Auschwitz on an American broadcast.

The FTP artists in turn had derived their Living Newspaper techniques from the early “Epic Theatre” productions of Erwin Piscator in 1920s Berlin. Historian Attilio Favorini describes Piscator’s legacy as “drama based on the principles of news reportage, constructed in an epic succession of tableaux and stations, and designed to promote direct social action….[by] bombarding the emotions with an arsenal of theater technology.” On the surviving recording of a live radio broadcast of the performance, one can hear how Hecht and his colleagues “bombarded” the audience with the percussive sounds of warfare while Waxman’s dissonant score almost drowns out the actors’ impassioned narration.

Further influence from the previous decade’s political theatre movements was evident in the participation in the pageant of several members of the Group Theatre and the Labor Stage company. The pageant’s chief director, Moss Hart, was not available to stage the new scene in Los Angeles, so that responsibility fell to his assistant Herman Rotsten, who had previously directed the national tour for Labor Stage’s Pins and Needles. The large number of extras needed to play Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto in the scene were recruited from the Actors’ Laboratory Theatre, a Los Angeles company founded by former Group Theatre members who had moved west to work in films. Founded as it was by politically engaged actors (many of whom were later blacklisted), the “Lab” expressly promoted a “social approach to acting,” committed to “an intelligent appraisal of the social forces at work in this particular political period…as people who consider the preparation of democracy and democratic culture a matter of life or death.” Three of the Lab’s Group Theatre alumni— J. Edward Bromberg, Roman Bohnen, and Art Smith—acted in other parts of the pageant that night, and the Warsaw extras were mostly students from the company’s workshop.

We Will Never Die has long been of interest to historians as a rare example of high-profile public protest over what was only barely coming to be known about the Holocaust. (An Associated Press report on Nov. 25, 1942, was the first such story published in the mainstream American press; the New York Times only placed it on page 10.) But it also stands out in Broadway history as an early example of Jewish political theatre—not just political plays written by Jewish American dramatists (Clifford Odets, Elmer Rice, Marc Blitzstein, etc.), but theatre by American Jews expressly about Jewish political issues. Given the participation in We Will Never Die by so many artists from the FTP, Labor Stage, and the Group Theatre (including, notably, John Garfield), I like to think of it as constituting a lost Jewish chapter (albeit a late one) of that era of American political theatre Harold Clurman dubbed The Fervent Years.

Ben Hecht had not previously thought of himself as a political playwright, but in the 1930s he found himself radicalized by Hitler’s rise and felt called to join the greater antifascist cause as an expression of his long-dormant Jewish identity. By joining forces with what was then called the “Popular Front” coalition of liberals and leftists in arts and culture, he brought about a work of Jewish American theatre that was long overdue.

Following is the complete script of “The Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto” from We Will Never Die, reprinted with permission.

Episode Three: “Battle of the Warsaw Ghetto”

(The orchestra starts a faint musical overture. The music is woeful. It continues for a time in the darkness. Its sobbing changes gradually into a martial air. Finally the music becomes wild and we hear a battle march filling the darkness.

During this overture a wall has been placed on the stage. It is the ghetto wall of Warsaw, 10 feet high and extends across the stage center. The lights go up. We see a street inside the ghetto wall.

It is night. The street is empty. The music ends. Two narrators appear at the microphones.)

MAN NARRATOR: This is the ghetto wall of Warsaw. Here no flag flies. Here no bugles sound. This is the wall of doom. Around it stands the might of the Germans. Tank divisions, bomber squadrons, the Elite Guards, and the storm trooper regiments surround this wall. It is ringed with death. The eyes of cannon and machine guns watch it day and night.

WOMAN NARRATOR: Inside this wall are the Jews of Warsaw—starving Jews, dying Jews, desperate and doomed Jews, Jews who were once scholars and workers, poets and artisans, soldiers, tradesmen, teachers—Jews who were once busy as human beings wait behind this wall for death. No flag marches to their rescue. No distant bugles sound with hope. Only one activity remains—that of dying.

MAN NARRATOR: They have only one weapon against the might of the Germans that watch the wall. Their weapon is the spirit of man. This remains. Massacre has not blunted it. Doom has not rusted it. Bright in the history of man are the battles that were fought with this spirit—the unconquerable spirit that shines forever above the victory of its enemies—Thermopylae, the Alamo, Bataan, Stalingrad—here is another battle to place beside them—the battle of the Warsaw ghetto. Here is a battle in which Jews, outnumbered one thousand to one, fought the might of the Germans to a standstill for three weeks. And though every one of these Jews is dead today, though every man, woman, and child who battled behind the ghetto ramparts has been exterminated, though the ghetto today is empty—empty as a beggar’s tin cup in the rain—the spirit of these doomed and half-starved warriors will rise forever among the highest flags of history.

(During the narrator’s talk, groups of men, women and children have been appearing in the street. Old men with prayer books in their hands have appeared and stand facing the wall and praying. Women, holding fast to their children, have appeared and stand in huddles. Younger men have appeared carrying loaves of bread. They cut small slices and give them to the women and children. They seize on the bits of bread and eat like starving people. The bread-bringers offer pieces to the old men praying. The old men refuse the food and continue at their prayers.

The woman narrator continues the talk, and as she does, the street continues to fill. Ragged, gaunt figures appear. In the corner a woman falls dead. Her children sit crouched around her until she is picked up and carried away. Women sit weeping against the wall. A young man in tatters enters the street. He is playing an accordion. He plays as he walks. The tinny music attracts three little girls. They form a circle, holding hands, and dance around and around as the accordion player pauses to play for them. Then the accordion passes on down the street. The three girls and an old man, who can barely walk, follow after the music.

Four men pass through the crowd in the street, bearing a coffin on their shoulders. They lower the coffin and open it. They remove old rifles and ammunition from it and distribute these to the men and women.

A stalwart working man appears carrying a large pot. It is full of soup. He pours a bit into each of the cups that are held up eagerly by the starving crowd. The figures in the street continue to move slowly across the stage. Half of them collapse against the wall. The others continue on.

During the foregoing, the woman narrator has been talking.)

WOMAN NARRATOR: In 1941 there were 400,000 Jews in the ghetto of Warsaw. There were another million in the other ghettos of Poland. In 1941 the orders came for their murder. Joseph Paul Goebbels, speaking for the German people, proclaimed over the radio.

GOEBBELS’ VOICE (coming through another microphone): “The extermination of the Jewish race is of historic importance and there can be no mercy.”

WOMAN NARRATOR: That was the order. That was part of the German bid for greatness. Within six months the order was being fulfilled. Within six months the cities of Białystok, Grodno, Brest-Litovsk, Vilna, Chełm, Kraków were “Judenrein”—clean of Jews. Every Jew in them had been slaughtered.

MAN NARRATOR: The killing of one million and a half human beings, even though they were helpless and unarmed, required organization and called for ingenuity. And these are talents in which the Germans excel. The Nazi governor of Poland, General Fischer, fell eagerly to work establishing extermination camps.

WOMAN NARRATOR: Remember these names—Trawinke [Trawniki]…Oświęcim [Auschwitz]…Tremblinka [Treblinka]. Remember particularly the name of Tremblinka. These were the organized extermination camps. In Tremblinka 7,000 Jews a day were put to death in special steam chambers and the mobile lime pits devised by General Wilhelm Krueger.

MAN NARRATOR: All of the doomed Jews of Poland passed through the ghetto of Warsaw. Warsaw was the embarkation center for death. A million Jews passed through the ghetto of Warsaw on their way to Trawinke, Oswjecim, and Tremblinka—on their way to the steam chambers and the lime pits. The ghetto of Warsaw was ringed with the Nazi divisions, cut off from the world like a section of limbo. But through its walls trickled the cry of the doomed—a faint cry of millions dying that found no echo. No saviors signaled from Heaven or earth.

WOMAN NARRATOR: On the 17th of March, 1943, there were left 35,000 Jews in the ghetto of Warsaw—35,000 Jews and a million ghosts. And on March 17th the Nazi Governor of Poland, General Fischer, issued the order: “All the remaining Jews of Poland must be killed.” This order went to the tank commanders, to the bombing pilots, to the machine gun and artillery officers.

(The faint distant blare of a German march tune is heard. With it is the rumble of wheels and the sound of footsteps like the wind.)

MAN NARRATOR: On March 17, 1943, the Germans moved forward on their errand of extermination. The Elite Guards marched into the ghetto of Warsaw at noon. They had come to murder 35,000 helpless people. The Elite Guards arrived at the corner of Długa and Tonaistra Streets. These are street names to remember—for on the corner of Długa and Tonaistra Streets a miracle happened. Jews—young, old, weakened with hunger, half-clothed…Jews led by an engineer named Michał Klepfisz, met the Elite Guard with weapons in their hands—old guns, scant bullets, rusty bayonets—but still weapons, met the Elite Guard and charged them—scattered them and drove them out of the ghetto, killing fifty of their officers.

(During the foregoing we hear the sounds of distant shooting and the cries of battle. These are not too loud and continue softly under the voice of the narrator.)

WOMAN NARRATOR: Rally, Jews! Here are old guns from the Polish underground. Here are swords. Here are grenades from the hidden storehouses. And here is battle! Raise your barricades! March—one against a thousand, musket against machine gun, bayonet and club against the finest cannon of Europe.

(The street inside the ghetto wall becomes a hospital. Here wounded are brought and laid out. The distant cannonading continues. Now fires light up the city beyond the wall. The old men who have been praying turn to take care of the wounded. During the narration, groups of twenty and thirty men and women, carrying various arms, run through the street, shouting and waving their guns.)

MAN NARRATOR: The Germans brought up their crack divisions. Their famed cannon blasted through the ghetto. Bombers circled overhead dropping shells. Flame and shell filled every alley and highway. But in these streets of a million Jewish ghosts, the Jews held firm. They fought from house to house. They emerged with guns blazing from cellars. They leaped with grenades in their hands from rooftops. They stood firm behind barricades with machine guns captured from the storm troopers.

WOMAN NARRATOR: Day after day, through light and darkness, the battle rages and there are reinforcements. Five hundred young Jews, on their way to the extermination camp at Tremblinka, turn on their executioners. With the aid of Polish villagers, they overpower their murderers and run all night back to the ghetto of Warsaw to die in battle. Rally, Jews! There is only death at the cannon mouth. From the underground radio station SWIT on April 21 comes the single communique of the Battle of the Warsaw ghetto—

RADIO VOICE (through another microphone): “Death sentence has been proclaimed on the last 35,000 Jews in Warsaw. Gun salvoes are echoing in the streets. Women and children are defending themselves with their bare hands. Help us!”

MAN NARRATOR: This is the brief cry from the ghetto battle. The only words to come from the ghetto front. They are hurled at the world and the transmitter goes dead. But the battle goes on. The ghetto is in flames. Light, water, oil have been shut off. This is no armed fortress, but naked streets. There are no bomb shelters here. There are no bastions of cannon, yet the ghetto fights on. A thousand Germans are killed the first week, 2,000 the second, 3,000 the third. Coolly, boldly, the men and women of the ghetto stand at their posts, die at their posts, and not all the Elite Guards and the might of the German divisions can overpower them.

WOMAN NARRATOR: And against the ghetto walls the old ones have returned to their praying and the young ones who have no arms raise their voices and sing as the battle closes on them.

MAN NARRATOR: And now there are flags. Flags go up on the ghetto walls. Flags go up on the rooftops of the warehouses—the flags of faraway countries. The flags of Britain, of Russia, and of Poland rise. No help comes from these lands—but their flags are the faces of freedom, the faces of faraway freedom.

(The three flags have risen above the wall.)

MAN NARRATOR: This is the third week of battle and the cry spread through the broken streets of the ghetto, “German tanks are advancing! They are coming down Lange Street.”

WOMAN NARRATOR: Rally, Jews! The tanks will roll over the old and the dying, over the weak and the helpless. Rally and meet them!

MAN NARRATOR: This is the last act of the Battle of the Warsaw ghetto. With grenades and pistols, with clubs and swords, all who remained of the fighting Jews storm over the ghetto wall, shouting and singing. They leap from the wall into the street. They rush forward and hurl themselves at the Nazi tanks.

(During the last of this narration the street has filled with young men and women carrying guns. They bring boxes with them. The boxes are placed like steps against the wall. The fighters climb up on the boxes, one after the other, singing the battle song which was heard at the beginning. They leap from the wall into the street.)

FIGHTERS: (singing)

We the scum of the human chattel,

We of everlasting flight,

We will rise in fearless battle,

We who cannot live the night.

Tears no longer!

Tears no longer!

Let them taste the death they deal.

And though we die, we die in battle,

Not beneath the tyrant heel!

(The narrator stops. We hear for several moments the sound of shooting, shouting, wheels, clanking, and above these sounds we hear the singing. The young men and women who leap from the walls continue to sing. The old ones left behind raise their voices and join in the battle song.

The stage darkens. In the darkness the singing still continues for a few moments. The boxes and the ghetto wall are removed from the stage during the darkness. The singing ends. The orchestra starts up, continuing faintly the last song of the Jews. All is silent except for the music.)

MAN NARRATOR: It was a German victory. The German cannon destroyed the last of the Jewish fighters. All of them. Not one with gun or sword in his hands ended the battle until he lay dead. It was a great victory for the Germans. They marched into the ghetto triumphant and slaughtered the 13,000 unarmed old men, women and children who remained. All of them. The extermination of the Jews had been accomplished according to plan. There are only ghosts left in the ghetto of Warsaw today.

WOMAN NARRATOR: Herrenvolk of the Third Reich! Brave, goose-stepping Jew-killers! Swine-hearted knights of massacre and murder—what is it you hear in the ghetto of Warsaw today? Not moans, nor shrieks, nor cannons booming—but a song, faint and endless. The song of the spirit that drifts from every one of the stones you conquered—the song of the brave Jews of Warsaw that will outlive your victories.

(During the last part of the narrator’s talk, the voices have resumed singing faintly the battle song that led the fighters over the wall.)

VOICES: (singing)

Tears no longer!

Tears no longer!

Let them taste the death they deal.

And though we die, we die in battle,

Not beneath the tyrant heel!

(The narrator ends. The stage grows dark and the song continues in the darkness.)

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.