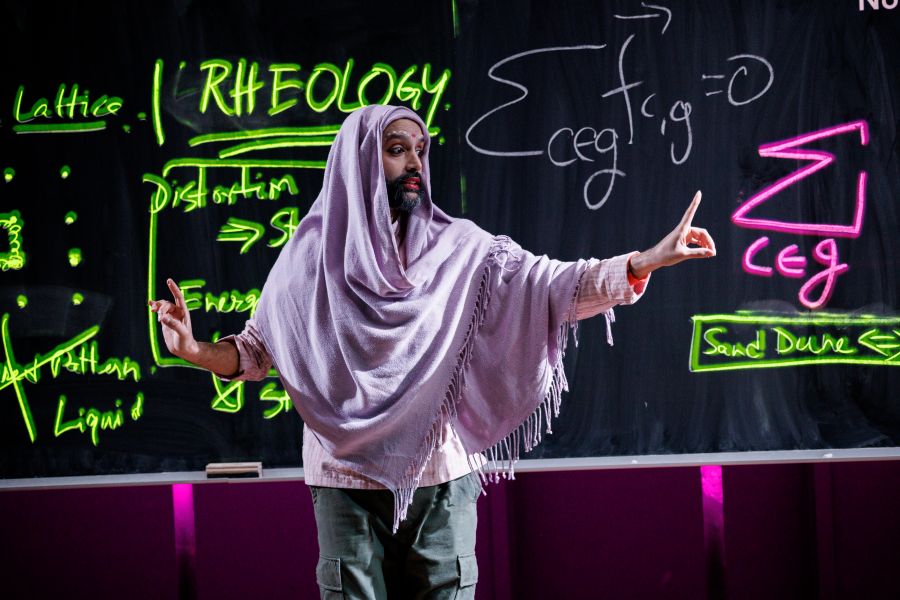

My first question for playwright Shayok Misha Chowdhury and his physicist mother, Bulbul Chakraborty—who appear together in Rheology, a beautiful and disarming 75-minute meditation on mortality and family at the Bushwick Starr through May 10—was a simple one: How on earth did you rope your mom into this?

For one thing, as I learned in a conversation with Chowdhury and Chakraborty at the intimate Brooklyn theatre, she required very little persuasion, as the two of them had been performing Rabindra Sangeet (songs by the great Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore) as part of a HERE Arts Center residency, in a piece that initially took shape as a kind of concert/memoir. And certainly her background as a lecturer on physics gave her some comfort and experience in appearing before an audience.

In fact, it sounds like it was Chowdhury himself—whose play Public Obscenities, first at Soho Rep in 2023, then at Theatre for a New Audience last year, immediately announced him as a major playwriting talent and made him a Pulitzer finalist—who needed some cajoling to get onstage.

“After Public Obscenities, I felt a little bit reticent,” Chowdhury said. “I was like, do I really want to do this weird, semi-self-producing three-theatre thing?” (In addition to HERE Arts Center and Bushwick Starr, Ma-Yi Theater Company is a co-producer of Rheology.) After years of working in experimental theatre and performance, in other words, Chowdhury felt he’d leveled up to “playwriting with a capital P,” and “no part of me really wanted to perform in a thing.”

But as time went on, he began to realize that trying to fulfill the HERE residency with “just a good, old-fashioned concert” wasn’t going to cut it. His mother was aging (in fact, she will soon retire, at age 71, from her post at Brandeis University), and his feelings about their relationship were changing.

“I realized I couldn’t put it off,” said Chowdhury, who is 40. “I was like, Will my mom and I be able to sing as well as we’ve been singing in two years time? There may not be—who knows…”

He trailed off before that sentence reached its morbid conclusion. He is less withholding in the show itself, in which onstage Misha puts it this way:

Recently…I’ve really been feeling like…or I’ve been feeling it pretty acutely, that the time my mom and I have left together is finite. And I’ve always had a phobia of my mother’s death. Before we started this process, I would have had a hard time even saying those words out loud, saying “my mother’s death.” So I guess we are making some progress.

So, with dates on the calendar and a venue booked, he felt like he had to “take advantage of this opportunity, even though it feels hard to do in this moment. That process led to us realizing, as we were building it: Oh, that’s kind of what the show is about.”

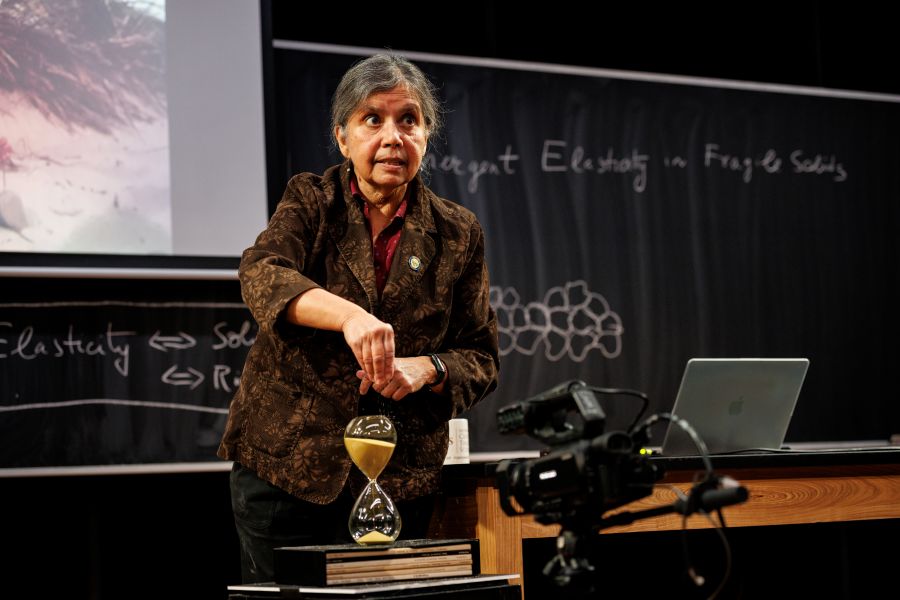

Before it veers into more theatrical and self-reflexive passages involving both mother and son, Rheology begins with a lecture about the physics of sand by Chakraborty, based on lectures she has done for decades. Indeed, she confessed to me that the toughest thing about working on the show with her playwriting son wasn’t the acting or singing—it was ceding control over that opening.

“The hardest part of that talk was relinquishing the writing of the talk,” said Chakraborty, a thoughtful woman with lively, attentive eyes and a ready smile. Or, as Chowdhury put it, “My mom’s had a difficult time being not the person in charge in this process.”

Onstage in Rheology, it must be said, Chakraborty has remarkable stage presence, both in the lecture passages and in more recitative and personal monologues, which is particularly impressive given that her only previous experience onstage was in a song contest in college and, briefly, as a performer and translator recruited for a play in Hindi because she was fluent in it (in addition to her main language, Bangla).

Her true performance training came many years ago, she said, from her thesis advisor, who helped her get past an early period in which, she said, “My talks were bad.” What did the trick, she explained, was her advisor’s practice of “moving the audience back a little bit every day before I came in, so that I had to speak louder and be more coherent.” By the time she was doing her postdoc, she said, she had people telling her she gave “beautiful talks.” Judging by the hearty engagement of the preview audience I saw Rheology with last week, it’s a fair review.

For Chowdhury’s part, it took years of stage work, including an MFA at Columbia, to overcome his innate introversion. Speaking for both of them, he said, “Neither of us are particularly comfortable in our bodies, or are natural-diva-energy-love-to-be-in-front-of-people kind of folks. We are shy, worried people. So there was a kind of finding ourselves through performance training.”

Ironically, the one member of the family who has been a lifelong performer is not onstage: Chowdhury’s father and Chakraborty’s husband, Partha Chowdhury—whose day job is also as a physics professor, at UMass—has worked with his son on creative projects before, and recorded a crucial voiceover used in Public Obscenities. Recordings of family members have been an unlikely throughline in Chowdhury’s theatremaking, in fact: The sprawling yet sharply focused Public Obscenities, a three-hour epic of Chekhovian detail and surpassing humanism, had its roots in a voice memo Chowdhury made of his uncle telling him about an especially vivid dream. Likewise Rheology has at its core a sort of family field recording: Chakraborty’s mother, at age 91, singing a Tagore song about a waterfall and an avalanche.

When a portion of that video plays during Rheology, and Chakraborty sings along with the image of her own deceased mother, she is visibly moved. “The emotion just comes,” she told me. So does a vivid memory: “My mother made me dance to this poem when I was 6 years old—she designed this whole piece where the sunshine comes in. I was the sun and my sister was the waterfall. On the terrace of our house, day after day after day, we did this.”

This ritual, joined by other family members, became even more central after Chakraborty’s father died when she was just 23. “It’s how we would gather,” Chakraborty recalled.

Ritual performances to process life in the face of death would seem to be a family tradition. In MukhAgni, at 2020’s Under the Radar Festival, Chowdhury and his partner, Kameron Neal, contemplated and rehearsed their own bodily deaths with a show they called “an automythography.” Chowdhury’s credit in that play was “director and script architect,” as he had incorporated material from Neal in a way analogous to the way he collected and curated his mother’s words for Rheology (though the credit this time reads, “Written and directed by Shayok Misha Chowdhury in collaboration with Bulbul Chakraborty.”)

I confess I’m still stuck on the anomalous wonder of that collaboration. What is it like to make a show, not just about your mother—a stock in trade for many a dramatist, often with an axe to grind—but with your mother? Chowdhury puts it delicately and thoughtfully.

“The process has been about, can we actually take each other’s disciplines seriously and not reduce it to simple metaphor? If I take the dramaturgy of my mom’s research seriously, can I make a new kind of theatre from the way that she actually works? Is there something about the actual physics of sand that can inform how we structure a piece of theatre?”

At the intersection of science and performance is a common concept: the experiment. If, as the onstage Misha puts it, his hypothesis is essentially that he can’t imagine life without his mother—that if she dies, he too will die—what would it mean to test that hypothesis in a piece of experimental theatre?

“To me, it feels very real,” said Chakraborty. “When I walk into rehearsals, the way everything works does remind me of when I walk into an experimental colleague’s lab. I am kind of an outsider there; they don’t let me touch things. There they try to figure out, what experiment can they design? Or they would say: Well, that we can’t measure.”

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.

Related

HERE Announces 2020 HARP Residencies

The four artists will begin their residencies immediately, creating three new theatrical works.

In "Awards"

Whiting Awards, Blue Ink Award, and More

A roundup of prizes, fellowships, and other recognitions.

In "Awards"

Grill & Chowder Win 2022 Relentless Award

The winners will receive $65,000 along with opportunities to have their musical developed at various theatrical institutions.

In "Awards"