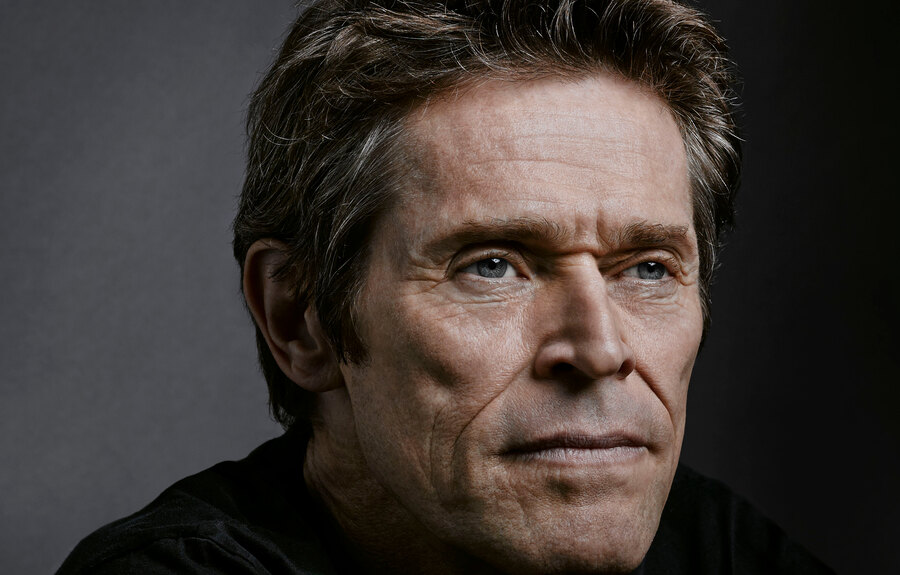

“I didn’t want to go shopping,” said Willem Dafoe in a recent Zoom interview from his woodsy study in Rome. He was talking about his approach to the job of programming the 2025 Venice Theatre Biennale, taking place on the Italian island city May 31-June 15, as part of a larger celebration of film, dance, architecture, and music. As a lifelong performer and audience member who will turn 70 this summer, Dafoe didn’t really need to go shopping to find “people I’ve worked with, people I’ve admired, people that I have some connection to,” to fill out the festival’s weeks of programming.

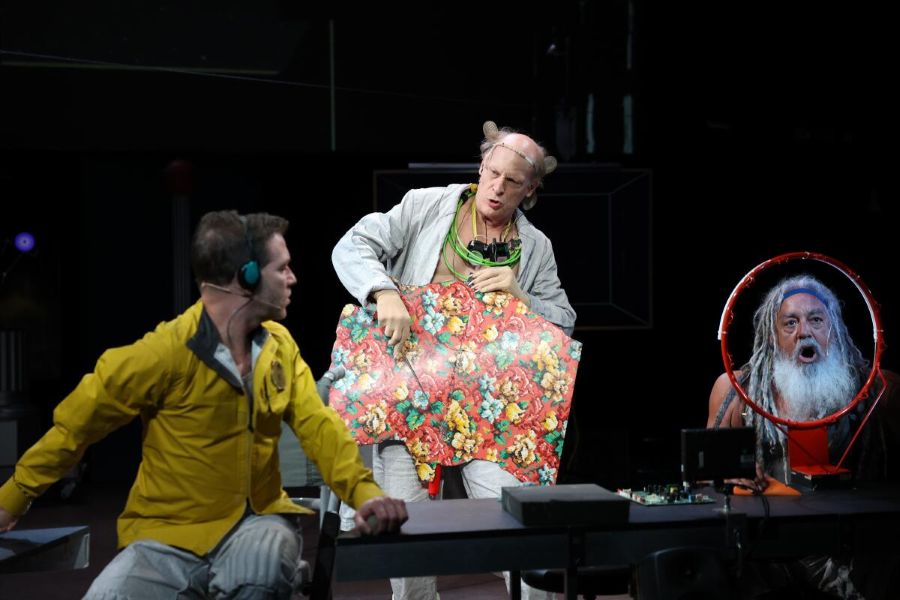

So his slate includes work by a few European heavy hitters—Thomas Ostermeier, Milo Rau, and Romeo Castellucci, the last of whom Dafoe worked with, on 2016’s The Minister’s Black Veil—as well as from a troupe with whom he was identified for a quarter century, the Wooster Group, who will bring to Venice their Symphony of Rats, a Richard Foreman play they staged in New York City earlier this year. It also includes a street performance by the American poet Bob Holman, in collaboration with the Italian collective Industria Indipendente, and work by Norway’s Odin Teatret and by Grotowski inheritor Thomas Richards.

I spoke to Dafoe yesterday about the festival, his early theatre years, and how he keeps the work fresh.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: How long have you lived in Rome?

WILLEM DAFOE: About 20 years ago, I met my wife [director and screenwriter Giada Colagrande], and I started spending time in Italy. I was a New Yorker for many years, and then I’d go back and forth. I still keep a place in New York, but I find myself in Italy much more. It really depends on where I’m working.

Is that how this Biennale gig came your way?

I don’t know how it came to me, quite frankly. I’ve worked in Italy as an actor, both with Italian and non-Italian directors. The president of the Biennale just called me up and said, “Would you be the artistic director?” I was very flattered, and I thought it would also be a good opportunity to sort of return to the theatre. Not that I’ve been away so, so long, but lately I’ve been very busy with film work. You know, I was very much formed by the theatre, and for many years, I worked daily at the Wooster group when I wasn’t on a film set. So my identity is still very much as a theatre actor.

We talked to you when you did The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic in 2013. Was that your last time onstage?

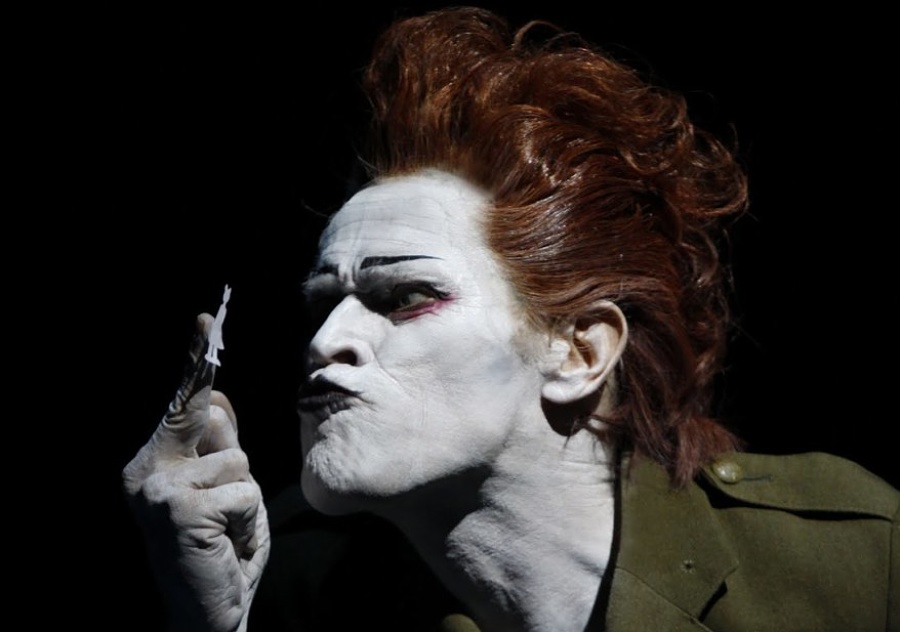

No, since then, I worked with this Italian director, Romeo Castellucci. He’s not so well known in the States, but I’ve followed his work for years, so I was very privileged to work with him.

He may not be widely known, but he’s known to folks who follow the theatre. Indeed, he’s among the international heavy hitters you’re programming, including Ostermeier and Rau. Another big name in the mix is your old troupe, the Wooster Group.

Yes, they’re coming with one of their pieces, and Elizabeth LeCompte is going to receive the Golden Lion. I have a lot of respect for her. She’s been making interesting work for 50 years, work that has never ossified or become flat. Even though the company has changed through the years, it’s a true company in that they work every day. And this is a woman that has never missed a performance, even when we were on tour. We used to rehearse before we’d do a show. So she’s tireless. She loves what she does, and she’s one of these people that really gives her life to what she does. I’m always very moved and inspired by that.

It seems like it wouldn’t be a Willem Dafoe festival without the Wooster Group there, right?

Thank you. I mean, it raises some eyebrows, because Liz used to be my partner, and I have a son with her—so full disclosure. But I stand behind the decision. She is really phenomenal.

It’s like being a Beatle—you’ll always be a Wooster Group guy.

Well, 27 years of working every day really makes you part of the family. I was the youngest one when I started out in the group, and then I became the oldest apart from her, and then I started making films and, for some personal reasons, moved to Italy. It all changed, but I’ve always followed their work.

I want to ask you more about the programming, but first, you brought up a theme I wanted to hit, given your long career. What happens when the youngsters, the upstarts, become the veterans, the elders? How do you keep the work fresh?

I’d say that’s an individual thing, and you’re lucky if you can do it. For me as an actor, it’s always about variety and curiosity, and I’ve been fortunate to work with all kinds of people in all kinds of situations. I can say that whether it’s programming this Biennale or making a theatre piece or working on a movie, every time I start something, it feels like the first time, in the respect to the elements that go into what your job is.

You know, when people talk about acting, when they talk about theatre, there’s always a tendency to put it in one little box. With theatre, the wonderful thing about it is that it’s a multi-disciplinary thing. It uses all the arts. You really recognize that when you’re programming something, because, what is theatre? All of a sudden, you may lean into some dance theatre, and people are like, “Whoa, that’s dance!” Or you may lean into something that has no words, and they’re like: “Is that theatre?” Or you may lean into something that’s very involved with music or architecture, and they’re like, “Whoa.” But the beauty of theatre is that it can deal with all those arts. It’s a total art. That’s one of its pleasures.

You do have a sort of manifesto for your programming that you’ve released, titled, “Theatre Is Body—Body Is Poetry.” Part of your point is that the human body is uniquely at the center of the theatre. Could you talk more about that?

Sure. I’m not talking about the body only in the sense of flexibility and the ability to express things through the body, but also the presence of someone in a room in front of a public. Outside of the performing arts, you don’t have that kind of meaning. The most important thing is that sense of presence. Most of the work that I’ve done and that I’m interested isn’t in a huge theatre where people are little specs; it’s a little more, you’re in a room with people doing things. And so, between ritual and movement and expressing things that don’t necessarily fall into a neat play form—that for me is living theatre.

“The body is intelligent. It does things that we don’t even control. And any time someone commits to an action, something can be expressed that’s beyond our experience; something really magical, quasi-spiritual can happen.”

The other thing is: The body is intelligent. It does things that we don’t even control. And any time someone commits to an action, something can be expressed that’s beyond our experience; something really magical, quasi-spiritual can happen. I like the opportunity to be in that kind of space, emotionally and physically. You can do that in theatre, and it’s much more limited in other forms.

The programming is divided into sections: a celebration of the past, looking back at the 1975 Biennale led by Luca Ronconi; the “maestros,” including Ostermeier, Rau, and Castellucci; and work that represents the future and student work. Was it your idea to categorize the offerings this way?

I really just thought about what would be good. I had some consciousness that there would be emerging artists, there would be established artists. But it wasn’t something I planned; it’s something something that kind of naturally happened as I was looking around.

As far the hearkening back to that 1975 Biennale, that’s expressed mostly in talks, inviting people like Richard Schechner to talk about the origins of theatre today, what’s been lost, what was won. It’s not nostalgia; it’s not academic. It’s really just to see where we’re at and kind of enjoy the people that contributed to forming our ideas about theatre.

I started out as a kid with Theatre X, a small company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and there was a small press bookstore in the lobby of our little theatre. I would be reading TDR and these books about Richard Foreman, Bob Wilson, Grotowski, and that really inspired me and sent me to New York. Ironically, when I got to New York, I intended, just for practical reasons, that I would pursue a traditional theatre route. But I kept on finding myself going down to loft performances and watching dance—watching stuff that even defied the Off-Off-Broadway of the time. It was a thing unto itself. That’s what brought me to the Wooster Group.

Almost everyone who was at that 1975 Biennale had a huge effect on me, so that’s my personal expression that I am a product of what those people made. I saw their pieces, I listened to them, I worked with some of them.

In this context, I’m curious how much the early Wooster Group was influenced, or got to see, international work.

We toured a lot, so we saw a lot of companies. We were very influenced by what we saw. We also saw over time how the European avant-garde was influenced by the work of the Wooster Group, particularly the practical use of technology. Liz was quite good at pioneering using very simple home-level video and tape. We were solving for production problems—you know, our 80-year-old actress couldn’t be there, so every once while we’d put her on tape and roll out a TV and play the scene with her on the TV. It wasn’t necessarily a considered aesthetic choice; it was a practical choice.

Wow, I had no idea.

It’s funny to have seen the origin of that, and then to see people take that language to do something else. It’s an interesting discussion and appreciation.

“You know, sometimes I sit in a theatre and I think, ‘Oh my God, there’s 500 beating hearts here.’”

There’s one piece among the newer groups I wanted to ask you about, and that is Davide Iodice’s Pinocchio.

I didn’t know about him; he was one of the few selections where the people I’m working with said, “Hey, check out this guy.” I went to Naples. It was actually very beautiful, because I had come from Los Angeles and I was very jet-lagged. I had three hours, so they said, “Why don’t you take a nap before the show?” They offered me the couch in Eduardo di Filippo’s dressing room, which is like a little museum. I slept on the couch that he slept on many times, so I have the fantasy that I sucked in some of his dream life as I laid there.

Sorry—I digress. When I got there, I saw the show is so beautifully made. Davide has worked in prisons, he’s working with older people now. He works with non-traditional actors, and he has a school for children, most of them with special needs. But they were all beautiful performers, because what they did was without ego. They had challenges doing simple things, but they did them wholeheartedly. It was what I really believe in, and that is a full expression of giving yourself to an action and submitting to an action. Naples is a great theatre city, and I felt like the audience was totally with the show. I checked myself to say: Why am I so moved by this? It was just the beauty of people doing things onstage that was pure and on some level expressed their humanity. It really got to the heart of that communal feeling that theatre can do so well, and sometimes is lost with all the commercial considerations and institutional considerations. You know, sometimes I sit in a theatre and I think, “Oh my God, there’s 500 beating hearts here.”

And apparently they all get in sync during a performance, which is wild. Last question: You’re doing a kind of performance as well. Can you tell me about that?

Richard Foreman, who died in January, who I worked with a couple times and whose theatre I would regularly go to, and who I loved—he called me and said, “When you’re in New York next time, could you come by? I want to make a recording.” So I went over to his loft building, and he was not so well. This was last year. He was in a wheelchair, but he was still very much intellectually turned on, and he had made these cards he wrote little phrases on—you know, “Tomorrow never comes,” or, “Never follow good advice.” Some were totally silly, some were very philosophical. They were all over the place. So he and I take these cards and shuffle them, split them in half, and then we alternate reading them in front of each other. It was beautiful, because these random phrases sometimes would come together in conversation and sometimes not. It was a word game, and it was also just about how we communicate. So we did a couple of rounds of that and we recorded that.

When he died, I thought it would be nice to do an homage to him. So we’re basically going to do that same thing in front of an audience with those cards. We’ll do two rounds in English and one round in Italian. It’s an experiment; it’s not about actors strutting their stuff but about trying to play with that thing which, when I did it with Richard, was very inspiring.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.