Jordan Harrison is a playwright, no doubt, but I also think of him as a kind of archivist of human behavior. I don’t mean that his plays are usually, or only, set in earlier eras; even when they have historic settings, there are contemporary intrusions, parallel plots, telling anachronisms. But in depicting relationships among people that span distances of time or memory, Harrison counterposes unlikely details and periods with a curatorial care. The time traveling is often literal: In Amazons and Their Men, Nazi-era filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl strives to make a film about the Trojan War, while in The Amateurs, a medieval morality play opens up portals to biblical times and to the modern era. Marjorie Prime envisions chatbot companions that could preserve our loved ones well into the future, ad infinitum. And in the unnervingly plausible Maple and Vine, the time-jumping is willful, as a harried contemporary couple flees the city to join a gated community that cosplays the 1950s. (That play headlines a new collection of his work from TCG Books.)

One way to view Harrison’s newest play, The Antiquities (opening tomorrow night at Playwrights Horizons, in a co-production with the Vineyard Theatre and Chicago’s Goodman Theatre), is as the fullest embodiment yet of his inner archivist. Spooling out a series of scenes from 1816 to 2240, then running back through them in time, the play is styled as a kind of living museum exhibit, concocted by the post-human, artificial-intelligence overlords who will inherit our world, to explain what humans were all about—with a special focus on the way we seem to have engineered our own downfall, though with some details tellingly awry.

Co-directed by David Cromer and Caitlin Sullivan, The Antiquities represents an ambitious effort to consider the ways humanity has been changed and could be changed further by technology, told in both broad strokes that feel adjacent to science fiction and in intimate sketches that give a large cast of characters theatrical, not to mention human, texture and dimension. It made me think of such theatrical antecedents as Churchill, Stoppard, and Washburn. But its otherworldly perspective and tragic scope put me more in mind of David Mitchell’s first two novels, Ghost Written and Cloud Atlas, which both explored synchronistic or unwitting links among disparate characters over a long span of time.

I spoke to Harrison last week about history, special effects, and an uncanny encounter with AI.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: I have to say, The Antiquities doesn’t just feel very Jordan Harrison—it almost feels like a summation of your work so far.

JORDAN HARRISON: I don’t know if I was aiming for an apotheosis, but I guess I was aiming big. My husband said to me in 2019, “You know, you have a lot of plays with four or five or six characters. How about taking a really big swing?” That seemed like a great prompt then, in our innocent pre-pandemic world. Now, of course, I understand exactly how unusual it is for a nine-actor play with 50 characters to get a production. And it took, in fact, three theatres and two directors to make that happen.

I read that you started writing this in 2019, before artificial intelligence became the stuff of daily headlines—which reminds me a little bit of how Jonathan Spector originally wrote Eureka Day, a play about vaccine skepticism, before Covid. How has your play changed since you started, and do you now worry about it seeming almost too ripped-from-the-headlines?

Well, I would never say I’m a prophet. I wrote the first draft of Marjorie Prime in 2012, when people weren’t generally talking about chatbots, though some were writing about it. And I wrote the first draft of The Antiquities in 2019, when the idea of the singularity, and of AI being sentient, was a little less upon us. I remember when I brought the first 30 pages into the Clubbed Thumb Writers Group, someone said, “Wait, we’re supposed to believe that AI wrote these scenes?” That was such a leap to consider just five years ago, and now, of course, we can imagine that AI would write a scene, because it’s doing it now and putting us out of work. So yes, the audience is a lot more sophisticated than the one I was writing for in 2019. But there are benefits to that too. I think people think of this as a more personal subject, one that touches their lives in a way that they didn’t then. That can’t be a bad thing.

I know Steve Cosson at the Civilians has been really into playing with chatbots, and their most recent show, Artificial Flavors, incorporated live AI-generated material. Have you experimented with chatbots and AI writing?

When I first set out to write Marjorie Prime, I wanted to write it with a chatbot as my co-writer, to see if it would pass the Turing test. In my mind, there would be two human actors onstage, and the audience would have to figure out over the course of the play which one’s lines were written by a human and which one’s weren’t. I tried that for all of 48 hours—I wrote the beginning of the play with the chatbot, and what came back to me was quippy, and it sounded a little bit personal, and that was impressive. But it wasn’t capable of coming at me with its own spirit or energy or curiosity. It got kind of tedious to talk to it. So I just packed up my chess pieces and made the play myself.

That was years ago. Have you tried since then—fooled around with ChatGPT or the newest one, DeepSeek?

No, I haven’t. I have a story about this. So because I’m a Luddite, I sent an email to 100 friends inviting them to this show, as though it’s still 1999—I don’t do social media. And I got a response from an old friend, and it started out, “What a wonderful evening of theatre. I’m so grateful to hear about it.” I thought: She sounds really off, what’s going on? As I read further down, she wrote that she had stepped away to get a cup of coffee, and her computer had just written the email response itself! She included the AI text in the email she sent. If anything, I felt this relief that it was still so easy to detect the absence of a real soul, right? I’m sure I’m going to eat my words in three months. But generally, when The New York Times or whoever does a quiz of whether you can pass the Turing test with an AI essay, I almost always can—still. Hopefully it’ll take a while longer.

Though this play is all actually written by you, what are some ways you tried to make it seem like it’s written by another intelligence? In watching it, I detected a few things that made me question the reliability of the narrator, so to speak.

I think of it as a little bit of sand in the ointment: You’re watching these relatively smooth and empathic human scenes, and then there’s a little hiccup. We’re calibrating this up to the last two rehearsals. There’s a moment with a rotary phone in the bar, where the barfly played by Andrew Garman dials the phone before he picks the receiver—it’s like AI has seen photos of humans using phones but haven’t quite gotten it right. This makes sense, because already you have these YouTube videos of teenagers not knowing how to use a rotary phone. And there’s a scene where a doctor uses a clarinet as a medical instrument.

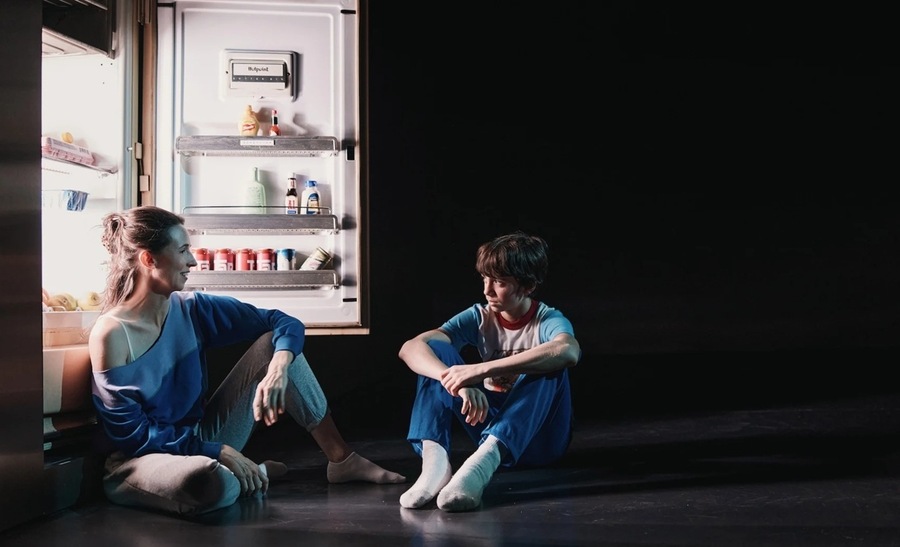

In the end, it’s a play that’s as much about humans as it is about technology. There’s a scene from my life in the year 2000, where some college students are sitting on the floor trying to remember a lost friend. I’m not here to pretend that AI in 2,000 years would rescue that scene from my life and make it more important than anything else in human history. It’s there because it’s important to me, you know?

I get the sense from the play that you’ve reached a sort of peace with the idea that humans are not the final word, that we’ll be replaced. Do I have that wrong?

Well, it’s become a more familiar idea to me, in working on this play, that we won’t be around forever—or that if we are, we won’t be recognizable to ourselves. At what point will it be inapt to call ourselves human beings anymore? I’m not even sure we would be recognizable anymore to my great grandparents if they saw us riding on the subway and staring at our phones, or if they saw my nephew playing a video game with 500 strangers as though it’s nothing. I guess my default used to be to think of AI and technology as a thing we had set in motion that had the potential to destroy us. Now it feels more like, they just will be the next chapter, and they’ll write it for themselves; we’lll either be there or we won’t. But it’s a little bit solipsistic to think of it as, like, “We’re Dr. Frankenstein, and that’s the monster that will kill us.” They’re indifferent to us.

Do you think of your work as being in the genre of sci-fi, or speculative fiction?

I’ve started to use the term emotional sci-fi more often. I’d love to get them, but I don’t know that my most natural audience is people who’ve spent their lives reading hard sci-fi. I tend to be a little bit soft-focus around the edges. Like in 100 productions of Marjorie Prime, I don’t know that a lot of people have been stuck on the issue of whether the primes are robots that you plug in or holograms. This is the kind of thing that took up a lot of rehearsal time talking with actors about. But as you’re sitting there in real time for an hour and a half, that’s not what our eyes pointed at.

In The Antiquities we learn that these human scenes we’re seeing are pulled from these few objects they’ve recovered in the center in the reliquary: a battered Soylent bottle, a battered iPhone, a cast with some signatures on it that they’ve reconstructed the way you would see a reconstructed Greek vase in the Met. From the emotional DNA of those objects, they have learned things about us. There was a draft of the play that got a little bit more into how they came upon these objects—that they were discarded by humans on their way to essentially internment camps where they ended up. I was like, I don’t care to dwell on that world building. I’ve made the mistake, in the far past of my playwriting career, of trying to explain too much. I think part of my art has become, as I said, making things soft-focus around the edges, and making us concerned with what the play is honed in on.

When you said emotional sci-fi, it made me think about why this story belongs in the theatre and not in another form. Film can be very literal—like, in the movie of Bug, they showed us that the bugs were real, while in the play we were never sure. Do you think about what telling this story in the theatre allows you to do, and also allows you not to worry about?

This play uses the same special effect that Marjorie Prime did: There are two actors in front of you, clearly human actors, and you have to learn through what they’re saying that one of them is not human. In Marjorie Prime, it’s on the first page, when one says, “I’m afraid I don’t have that information.” That’s not a thing you would say to me as an answer, so right away our ears prick up. In The Antiquities, when the lights rise on the prologue, we see two women dressed as early 19th-century women. One of them is pregnant. And they say, “You all look perfect. It’s like we’re really here.” That gets under our fingernails a little bit. If it were a movie, there would almost certainly be the temptation to put some Princess Leia glowing blue lines around those figures.

I think it’s a real question, though, whether technology is not only making AI more like us, but also rewiring our brains, making us more like computers. I may not literally say to you, “I don’t have that information,” but I can imagine saying, “Still processing”—possibly ironically, but still.

I mean, you’re hitting upon exactly why this has become my most frequent subject. I worry about: Is my brain changing? Is my relationship to my inner self changing? My relationship to my husband, to my parents? And changing how? What are we losing, if anything, because of the expectations that technology creates in our lives? The number one fight I have with my husband is about whether he’s available on his cell phone, because now we think that everyone is available all the time. The phone has changed the contract of what we think another person we care about should be doing.

There’s one thing I want to refine about my earlier thought. This show isn’t using the same special effect as Marjorie Prime, in terms of the flesh-and-blood actor playing a post-human being. Actually, I feel like The Antiquities is using the theatre of Playwrights Horizons itself as a special effect. It’s saying: This whole theatre you’re sitting in is not really here. It’s subverting, hopefully, the seats that we’re sitting in.

When we last spoke about Maple and Vine, I think you told me there was talk about it being made into a series, which I could easily imagine. What happened with that?

It went so much further and also nowhere at all. I sold it to two networks, got paid to write the pilot; a lot of fancy people were attached at various phases, including Yorgos Lanthimos. According to some screenwriters, nothing is ever dead forever, so I hope it comes back. My generous spin on why it didn’t happen—I don’t know if it’s generous to myself or to Hollywood, or maybe a little of both—is that it’s a scary story. The idea of a woman willfully giving up some of her freedom, of gay people willfully going to a place where they can’t be open—there always was darkness in that idea, and now, in the MAGA age, it is even more dark. It was a little bit whimsical then, the thought of moving to the 1950s, but now we’ve seen a very real example of people in our actual world chasing a mythological 1950s and its values. I’m hella curious how it will land on new readers in a TCG edition.

The first play I saw of yours, Doris to Darlene, made really unlikely and interesting links among 1960s girl groups, Wagner, and a more personal contemporary story. Similarly, I feel that while your plays have different themes and forms, they do kind of rhyme with each other.

I like the word “rhyme” for The Antiquities. I have the greatest of dramaturgs, Sarah Lunnie, working on it with me, and she uses that word a lot—that is the logic of the play. It’s not always explicit how one scene hands off to the next, but they always vibrate with each other. And of course we revisit each of these scenes, and so the scenes rhyme with each other too. If the first half of the play ends up being legible as a kind of march toward our own extinction, then, once we know where the human project ends and the plot is over, we go back down the other side toward 1816, and way it lands on me when we meet these characters again is almost a kind of elegy. I see that a cell phone contains the spirit of a grandfather, or a boy who had a fight with his best friend was able to talk to this Alexa-like program, which itself was made as a tribute to someone’s dear sister who passed away. It’s not as simple as, “The technology replaced us.” We reside in it; it’s inseparable from us, and we from it. That’s the kind of thing that sinks into me in the second half of the play.

Would you use the word “cautionary” for your work?

I certainly hope it’s not merely cautionary. I was thinking about this the other day vis a vis this play: I grew up in Seattle in the late ’80s and early ’90s, and it was all Microsoft. And then I went to Stanford in the mid-’90s, and my classmates were leaving school early to be the 10th person in the door at Google. Then I worked at Amazon in 1998, and sat there watching Jeff Bezos on a giant screen, like out of Orwell, talk about how they were gonna start to track what Aunt Susie wants for her birthday. That blew my mind at the time, that they would be able to erode privacy in that way.

So I’ve had a whole lifetime of being told that computers are the future, and sort of stubbornly being like, “Well, I still care about my dying art form, theatre.” Even in college, I remember having that thought process—like, I don’t need to get on that airplane that’s about to carry everyone away to fame and fortune. I have an ambivalence about technology that I can’t escape entirely, and it drives me to write. Maybe I shouldn’t try to escape it.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.