First, the silence. When I worked for Richard, I would show up early—an hour early, usually—and then Richard would show up, and we would sit in the theatre together in silence. I would go over my notes, set up the room, read; Richard would go over his notes, review his pages, read. We were comfortable in silence for long periods. I am convinced that this is one reason we always got along.

Richard, you see, always meant everything he said. He wasn’t rude or gratuitous, and he knew how to not say certain things, but if he said it, he meant it. This still astonishes me. It also would disconcert just about everyone who came in contact with him. I’ll never forget being met at the airport by the manager of a theatre where Richard was directing; she clutched my arm, looked me deep in the eyes, and said with intensity, “We’re soooo glad you’re here.” He’d been there for a couple of days when I joined the job, and they were all already in a panic. I think they just needed me to be a buffer for his way of speaking or not speaking. Richard never engaged in the small talk or verbal stroking we all use every day to smooth the wrinkles of interaction, which freaked people out. Nobody actually means everything they say. Richard did. I loved it.

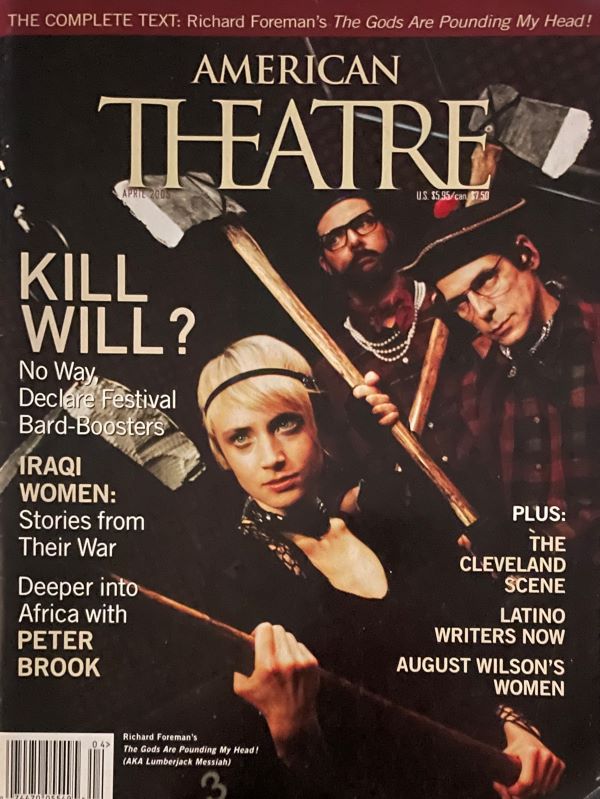

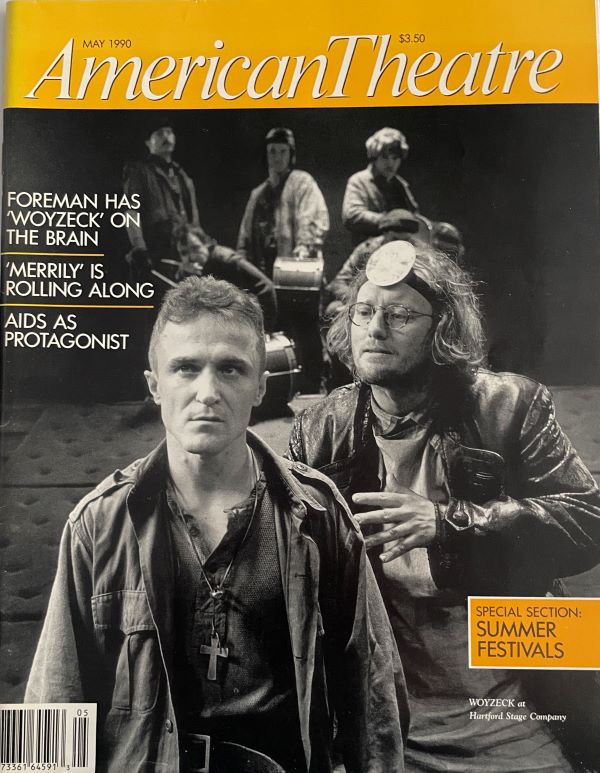

I don’t know if Richard really cared that I loved his silences; we were comfortable, and that was enough. I think he liked me because I showed up and worked hard to do what he asked of me. I assisted him on many shows from 1988 to 1992. The last one, The Mind King, was his first production at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, the place that became a celebrated home for his work. After that I would visit his rehearsals from time to time, just for the pleasure and relief of it; those days had become a home to me, and a refuge. Now the memory of it will have to do.

When he did speak, Richard could be a charming, garrulous, even impish interlocutor. I heard him many times refer to himself as “antisocial.” He believed it, yet this was not exactly right. He would rise to social occasions every time, right up to his last appearance at the NYU Skirball Center, crowded with admirers, on Oct. 6 of last year. Ask a good question and the man could talk.

For all his skill with thought, Richard showed me that real, powerful work springs from not thinking. He would work intuitively, randomly. His work was just his self. Everyone’s ought to be.

Richard’s influence is unquantifiable, as countless people he shepherded have written. So many things he said in my hearing have stayed with me and inspired me every day. “You make yourself, and then you make your work,” is a favorite. At the end of the day, after all the intellection, the essays, the references and brainy talk, we all make the work that we feel is beautiful, important, true, and moving, and that making happens beyond places in the brain. For all his skill with thought, Richard showed me that real, powerful work springs from not thinking. He would work intuitively, randomly. His work was just his self. Everyone’s ought to be.

Often in approaching Richard’s work, people (critics, scholars, other artists) are seduced by the intellectual intricacies. They mistake verbal dexterity, abstraction, and philosophy for the substance of what is going on. For me that is not the case. That artful abstraction is Richard’s mode, his way of working things out into a physical presence, but everything is driven by raw, inchoate carnal passion. The work attempts to manifest that messy human stuff and render it so we can engage with it anew. My Richard Foreman is more driven by lust than loftiness. More grind than grand.

One dimension of his self that informs all his work is this: Richard was nothing if not critical. He was ruthless in cutting himself, instantly spotting the choices and words and motions he had created that rang false. I watched him throw away weeks of work in a minute, and that was a not infrequent event. This could be tough on collaborators, actors especially. Time and again I would cringe inside as he said to a cast after a rehearsal run, “That was awful…[pause]… just awful. Not you, I don’t mean you. It’s me, my work is terrible.” He meant it (see “everything he said” above), but of course the actors would be crushed. My job was often just bucking them back up as best I could. Still, his coldness with his own work is an inspiration to me.

Then again, he wanted people to like the work. He knew that audiences are fickle, that his taste would not be shared by many, and that his work would be a challenge to them—despite all of which he wanted his plays to reach as many as possible. He cared deeply about filling the house, about people being moved and inspired, about their engagement with his imagination. All this is trivial and out of our control, next to the integrity of the work itself, and Richard would be the first to say “so what!” and to wear walk-outs as a badge of honor. But he cared.

Here is a story María Irene Fornés told me years ago, in confidence, which she did not want to share with Richard. Now that they are both dead, maybe I can share it with everyone. Irene went to one of Richard’s plays back in the ’70s, in the old loft on lower Broadway, and a hockey buzzer was going off. Loud. Throughout the action, without relief. She was in agony. “This is painful, I don’t get it—why?” and then it hit her: Richard was saying, Get out. Leave the theatre! Do something! She got up and walked out. Days later, when they ran into each other, he said, clearly a little wounded, “Why did you leave my show?” and she made up the usual story about a sudden stomach illness or something. I never told him.

As I said: Richard cared.

David Herskovits is the founding artistic director of Target Margin Theater.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.