In a large, adobe-clad art gallery in the heart of Santa Fe, N.M.’s historic district, I walk into a cluttered, industrial-looking room and intrude on an argument between Hamlet and Horatio. I slip into one of a handful of flimsy plastic chairs strewn around the room. Horatio tells Hamlet to follow him, snaps on a couple of eerie green LED lights, and stalks out. She follows and we tag along. The argument escalates as we arrive in a shadowy, cavernous gallery.

Suddenly Horatio stops and points out the window. Outside, about 30 feet away, a tall, sleek figure in a black mask lingers. Horatio tells Hamlet it’s the ghost of her father. Hamlet goes outside, and though we can’t hear what she and the ghost are saying, we creep toward the bright window and try. It feels like we’re inside a movie, in a moment somehow both cinematic and theatrical at the same time. Hamlet eventually returns and drops the famous bombshell: The ghost has revealed he was murdered by her uncle and she needs to avenge his death.

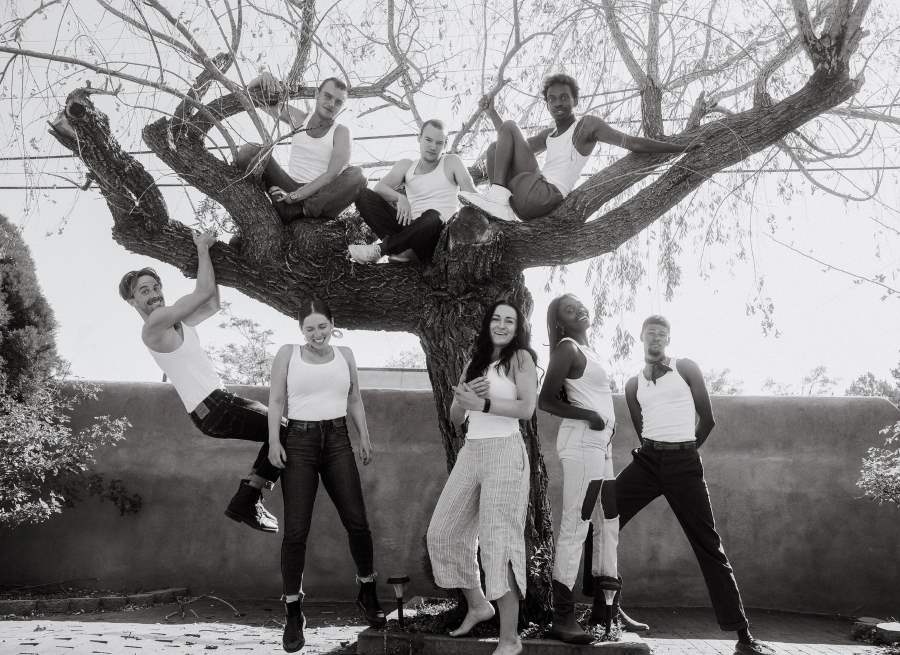

The scene breaks and director April Cleveland asks Kya Brickhouse, who’s playing Hamlet, and Mason Azbill, who’s playing Horatio, some questions about how the argument builds. Their language for the scene is improvised, but the structure of events still needs to make sense. She tells Patrick Agada, who plays Claudius and the ghost of Hamlet’s father, that she prefers today’s black mask to yesterday’s white—it feels more mysterious. Also, she notes, the seating in the small space feels too clinical, not enough like a living room. Maybe the stage manager, Zoe Mcdonald, can look into some low ottomans or poufs?

It is early May, and in just 30 hours The Exodus Ensemble will invite a friendly group of audience members to a run-through of the HAMLET they’ve been devising for three and a half months at Santa Fe’s Center for Contemporary Arts (CCA). It will be their first chance to get outside feedback on what they’ve been creating: a stripped-down, modern-language, mystery-steeped version of the classic story of grief verging on madness.

As with every show they make, their goal is simple: to provide audiences an antidote to boredom. Exodus wants to entice people who don’t typically go to plays; their website promises “incomparable immersive experiences that redefine, reimagine, and revolutionize how audiences encounter theatre,” and touts their shows as “a portal to bingeable, edgy immersive events that transform audiences, bending their minds and spitting them out feeling deeply alive and connected.”

While most of our industry shuttered during the Covid lockdown, Exodus was born out of the crisis. Cleveland, Exodus’s director, burst out of the DePaul Theatre School’s MFA in directing program in the spring of 2019 with a full schedule. (Full disclosure: I was one of Cleveland’s main professors, and taught many of Exodus’s founding ensemble members at DePaul.) An assistant director at many large theatres in Chicago, she was slated to open the Paramount Theatre’s new second space, and serve as associate director for British wunderkind Robert Icke on two West End transfers when the pandemic lockdown wiped out all of her work plans in a matter of days.

Her partner, Kit Slover, had just landed a full-time teaching job at St. John’s College in Santa Fe, where Cleveland went for undergrad. It seemed as good a place as any to sit out the pandemic. On the way to Santa Fe, Cleveland had a vision: She began to imagine her favorite DePaul colleagues making theatre in the desert. That night she dashed off an impassioned nine-page email.

“Dear friends, fellow conspirators, and most esteemed collaborators,” Cleveland began. “Your talented, wild presence is requested in the desert to create, invent, inaugurate, and articulate a highly ambitious, extremely playful, groundbreaking, and desert-shaking new performance ensemble.”

Almost everyone who opened the email joined her in Santa Fe in under two weeks, and had the good fortune of finding housing in a vacation home that was sitting empty. They spent months dissecting what they loved and hated about theatre, creating short theatrical pieces, and agreeing that they wanted to create risky, immersive experiences. They started devising a production based on Anton Chekhov’s Ivanov, and after four months of work they unveiled a four-hour production for just two audience members: Slover and Maggie Thornton, creative producer for Meow Wolf, a Santa Fe-based company that creates explorable multimedia art exhibitions. Thornton was enchanted.

“I told them, with utter sincerity, that IVANOV was a peak artistic experience of my life,” Thornton raved to me via text. “They had gifted me something, a piece of myself, a seed for the future. It reinvigorated my passion for storytelling and world-building and had me reconsidering all the ways I generate ideas in my own work.”

Thornton begged the ensemble to put down roots in Santa Fe, and gave Cleveland some advice on starting a company. In the following three years, The Exodus Ensemble produced five new immersive works, including DEATHCOOKIE, a murder mystery commissioned by Game of Thrones author George R.R. Martin for his Sky Railway Adventure Train. Like some European ensembles, Exodus performs their shows in repertory, presenting JAYSON, a modern two-person riff on Medea, one night, and ZERO, a game-infused participatory story about AI and corporate greed, the next.

In January 2024, they began devising their sixth piece, starting with “pitch week.” Ensemble members gathered to sell each other on plays in the public domain, arguing the merits of the plays, reading sections out loud, and viewing inspirational videos.

Two plays rose to the top: Desire Under the Elms and Hamlet, each garnering three votes. Ensemble member Kya Brickhouse held the deciding vote. It was clear to everyone that Brickhouse, a young Black female actor, would be the lead in the Shakespeare play if it was chosen. But she had doubts. She excused herself for a moment.

Outside, Brickhouse lit up a smoke and asked herself if she really believed she could embody the most famous character in English literature. Would audiences accept her in the role? She flipped a coin. It was tails: Hamlet. Brickhouse, still nervous, prayed on the outcome.

“I said, ‘Are you there, God? It’s me, Kya…Are you sure?’ I flipped it again. God said Hamlet, and then I flipped it again, because I was like, ‘Am I tripping or what? What’s going on? Are you sure?’ I flipped it for a third time, and it was Hamlet.”

I’ve been in conversation with Cleveland since the founding of Exodus. In March 2023, I went to see four of their shows in one weekend. These included IVANOV, in which actors lured audiences from room to room of a historic mansion, allowed us to eavesdrop on conversations, and pulled us into their family drama; and BATHSHEBA, in which we were instructed to arrive dressed in all white, only to find ourselves immersed in an eerily convincing cult initiation.

After each performance Cleveland gathered the audience and described the company’s business model. All shows use a pay- what-you-can ticketing model, and post-show donations range from $5 to $10,000. In their first year of operation Exodus pulled in just $200, but by the next they were up to $200,000, and in their third year they raised $600,000 from audience members and individual donors.

Exodus keeps their overhead low so that the money can flow back to the artists. Most ensemble members serve two roles, creative and administrative: acting and devising on the one hand, but also working in casting, audience services, tech, development, or marketing. Every ensemble member starts at the rate of $18 an hour for performances, and $16 for any other Exodus-related work, with hourly rates rising the longer they work for the company. The company has also offered ensemble members housing stipends to allay the costs of living in pricey Santa Fe. At one fundraiser, Cleveland told prospective donors that the company didn’t want to expand their administrative staff until all the artists are paid what they were worth.

As they have built infrastructure and repertoire, Exodus has scrambled to find performance spaces. They first performed IVANOV in the house they lived in, and went on to adapt the show to seven other venues. They worked out performance deals with local art galleries, and continue to perform DEATHCOOKIE on a train moseying through the New Mexico desert. In May 2023, they were granted residency at the Center for Contemporary Arts, a 45-year-old organization that faced struggles due to Covid lockdowns. When Exodus was presented as a potential partner for the center, David Muck, board chair for CCA, saw bringing in the company as a way to revitalize not just the organization, but the Santa Fe arts scene.

“Almost everyone here has an art form that they identify with one way or another,” said Muck. “It’s a really creative town. One of the things that’s exciting about Exodus, especially for the Santa Fe arts community as it ages, is that it’s fantastic to have this younger generation who’s going to keep the scene going. ”

Photographer Gabriella Marks seconded Muck. She’s lived in Santa Fe for 20 years, working mostly as a commercial photographer; when she started her career decades ago in San Francisco, she thrived on shooting indie bands and capturing their raw energy. She said she felt that same intensity the first time she attended IVANOV.

“I’d been binging TV during the pandemic,” Marks said, and Exodus shows made her feel “like I actually got to go in and be inside of one of my very favorite shows. It’s not virtual reality, it’s actual reality.”

In the HAMLET rehearsal room a table is littered with index cards with the titles of comps and little notes beneath. Comps, or compositions, serve as the core of Exodus’s art-making process. These short improvisations employ techniques outlined by Anne Bogart and Tina Landau in The Viewpoints Book—i.e., giving artists too many elements as prompts and a short amount of time. As Gracie Meier, who plays Ophelia, put it, “We rely on just an absolute wealth or mass of ingredients and way too little time, which makes you go feral in terms of just agreeing to get something out in the physical world.” Echoing Bogart’s language, she said, “It just creates the exquisite pressure of time.”

Eighty percent of what the ensemble created over the first three months sits on the cutting room floor, leaving their favorite moments to refine and build around. Much of their discussion now centers on how to connect one comp to the next, essentially writing a play on their feet. Time is running out, as an audience arrives in a few hours to see what they’ve created.

The ensemble faces a mountain of challenges. They’ve decided to turn their HAMLET into a mystery and are struggling to build real suspense onstage. Trying to lure the audience into Hamlet’s “mind palace” has forced them to keep Brickhouse onstage for every scene—exhausting for her, and possibly monotonous for the audience. Moving audiences around the several-thousand-square-foot CCA proves daunting.

I watch the company work through a comp they call “Talent Show”—their version of Shakespeare’s play-within-a-play, in which the performance of a murder drama is meant to help confirm Claudius’s guilt. The actors cement what pop songs they plan to sing, and Kirby leaves early to create a karaoke track. In the final act of the Talent Show, Hamlet enters to slow, dramatic drumming, bearing cups of water and clay. She mixes the clay with the water, puts the goop on her body in a rhythmic fashion, draws Claudius onstage, blindfolds him, then pulls out an urn. As she wipes clay onto Claudius, it becomes clear she’s rubbing the ashes of her dead father onto him to provoke a reaction. Horatio videos the entire scene, with the image projected behind on a large screen, providing the audience a closeup of Claudius’s reaction.

They start problem-solving: Should they maybe spray Hamlet down with water rather than use cups? What is the desired action Hamlet wants when she strips off Claudius’s blindfold? How does Cladius attack his niece? They’re not trying to cement a script, but rather home in on what they call a “roadmap.”

Ensemble member Garrett Young explained how roadmaps work. “There are parts of the roadmap where it says, ‘You can say “this” / “this” / “this” or “whatever you want.” An actor who thinks they’re reading a script will ask, ‘What does this mean?’ Well, it depends on the actor who’s playing opposite you and what they just said. What’s at the heart of the line? What’s the meat of the action? What are the dominoes that need to be knocked over in this scene? Without set lines, you are forced to actually, actually listen and truthfully respond.”

Like all of their shows, when HAMLET eventually enters the Exodus repertory and different ensemble members swap into roles (indeed, after its summer debut, the show would return in October), they feel it’s important that the language feels right in each actor’s mouth, regardless of how it was created.

Later that evening, a group of eager friends and family members audience members arrive at the CCA. We’re told that if we see a green light we should follow it, and any white furniture is safe to sit on. Everyone receives a notebook and a pen and is instructed to think about three questions: What did you like? Where were you confused? What questions do you have?

HAMLET opens with an arresting image. As an audience of 15 huddles in the doorway to the CCA looking out, Horatio abruptly enters our vision about 40 feet away from the door. In an added bit of drama the night we see it, just as Horatio stops, lightning strikes about a mile away. He hesitates, walks in among the audience, looks down a stairwell—and a mysterious figure in a black mask appears. Horatio snaps on handheld green LED lights, follows the ghost, and we do too. We end up in a bathroom with Horatio calling out to the ghost. The lights snap out. We’re in the dark. They snap back on, and we see Claudius and Horatio chatting about the upcoming funeral as they wash and dry their hands.

We’re led again to a cavernous space with a microphone set up at one end next to a stand with an urn. Claudius welcomes us to the funeral of his brother and starts giving a eulogy. Suddenly Hamlet appears, disheveled and distraught, just as a recording of her voice starts playing over the sound system. Claudius doesn’t see Hamlet as she approaches the urn and opens it up; a light shines on her face. The voiceover reveals how she couldn’t face going to the funeral and can’t really process her thoughts. It’s a moving theatrical exploration of grief, grasping at the same ideas as Shakespeare.

Over the course of the evening, we’re led to an office space, the foyer of the museum, and eventually back to the industrial space. Scenes that the day before were barely sketched out land with full dramatic intensity. While we are sometimes confused, we’re never bored, as we are drawn deeper and deeper into Hamlet’s madness and obsessions.

Just after a hallucinatory dream sequence between Hamlet and a sock puppet, she and Horatio plan their next steps. Ophelia interrupts them and Cleveland calls, “Hold.” We stop right at the cliffhanger, with Cleveland explaining that they aren’t ready to share an ending. Champagne is poured, people sit in a circle, and we offer feedback. People loved the music, being led around the gallery, and the intensity of Hamlet’s journey, but were confused about Ophelia and thought the top of the play lacked tension.

The day after the run-through, I meet up with Cleveland for coffee. What’s next? What will she do with the comments she received? She has five days before the next run-through, and just under two weeks before sharing the show with the general public. She doesn’t have an ending to the play yet, she’s not sure about the arc of the second act, and she doesn’t think she’s cracked the play’s mysterious core. But she knows that she trusts her collaborators—and the exquisite pressure of time.

Damon Kiely is an associate dean and professor of acting and directing at the Theatre School at DePaul University. He works professionally as a director and playwright and is the author of How to Read a Play, among other books about directing.

Support American Theatre: a just and thriving theatre ecology begins with information for all. Please join us in this mission by joining TCG, which entitles you to copies of our quarterly print magazine and helps support a long legacy of quality nonprofit arts journalism.