The postpartum-like depression that follows any creative act is familiar to anyone who works on a project-by-project basis, and most certainly to everyone in the arts. The book is published, the film or album released, the painting hung—now what? Do we really have to start over and do it all again tomorrow?

This morning-after crash is even more acute for those who toil in the ephemera of the performing arts—forms which live entirely in a series of shared public moments, only to be struck with the sets or packed away with the guitars or pointe shoes, the sole remaining record of all that effort existing in the individual memories of hundreds, possibly thousands of disparate people (not counting stray video captures and/or the things we theatre journalists write). To get up the next day and go through that dance of the mayfly again—most often not only with no hope of a durable record but with a strong likelihood you won’t receive extravagant material compensations either—might almost fit the famous definition of insanity as doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting a different result. A lifetime of such ups and downs is definitely not for the faint of heart.

Imagine, though, if you built an institution that could serve as a permanent container for such moments, a fixed address for these fleeting appointments—a garden where these flowers can bloom in their season, then be pruned away for the next. Might that give an artist some sense of continuity, lasting impact, artistic home?

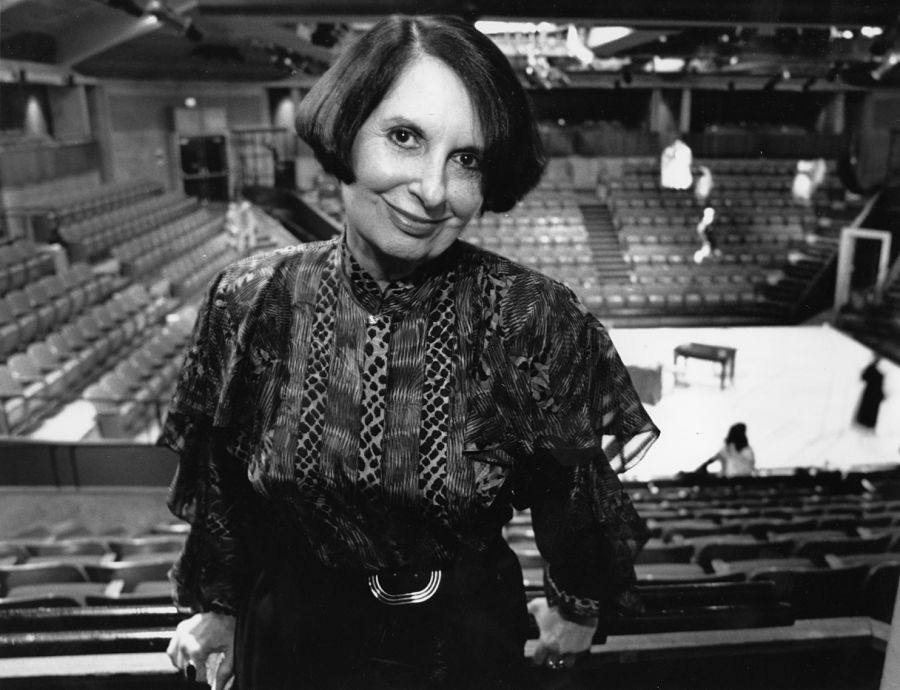

This is the question I kept coming back to as I read two indispensable new books by and about Zelda Fichandler, the late, great co-founder of Washington, D.C.’s mighty Arena Stage, who died in 2016. Fichandler inarguably built one of the nation’s leading arts institutions around precisely this impulse—to make for theatre artists, as she often put it, “a home and not a hotel”—and in so doing inspired generations of leaders and artists (which she also did in her subsequent role as head of New York University’s graduate acting program).

But rest on her laurels? Nope. On the evidence of the speeches and essays collected and lovingly edited by Todd London in The Long Revolution: Sixty Years on the Frontlines of a New American Theater, Fichandler was hardly shy about celebrating the achievements of Arena and of U.S. regional theatres more broadly. But she could never be mistaken for a simple cheerleader. In a 1970 essay, she tidily sums up the rationale for the movement she helped pioneer over the previous two decades: “The impulse…was to remedy a grievous fault and reverse a direful trend—the contraction and imminent death of the theatre. The goal has been, to a large degree, accomplished.” She hastens to add a cautionary note: “Not secured, but accomplished.”

More plaintively, in a 1967 speech, she wonders aloud:

How old do you have to be to be “permanent”? How far up is “up”? Where are you when you are finally “there”?…When I get up in the morning I feel about twenty-eight days younger than the Comédie-Française. When will the proof be acknowledged to be actually in the pudding? How long must we scramble, pushing that damn stone up that damn mountain only to have to push it up again? How long, O Lord, how long?

A certain divine dissatisfaction also thrums throughout Mary B. Robinson’s extraordinarily vivid mix of oral history and biography, To Repair the World: Zelda Fichandler and the Transformation of American Theater, in which Zelda is quoted as saying, philosophically, “It’s never all in place. It never needs to be in place. Motion, change, transformation—that’s where the energy comes from.” That is also where the anxiety comes from: In an impassioned letter to the Ford Foundation, whose largesse helped launch Arena but whose direct support waned over the years, Zelda wrote, “I feel that there is no more successful theatre anywhere and NONE THAT IS IN A MORE PRECARIOUS POSITION.”

Robinson’s book even winds up in meta-contemplation of The Long Revolution itself—a collection that was in the works before Zelda’s death but was only completed earlier this year. Robinson quotes London on Fichandler’s “Jewish and Talmudic” impulse to “keep questioning the thing that you’ve made.” London adds, poignantly, “Without the opening night, or without the structure of school year/graduation, she couldn’t bring herself to stop the process. It just felt so continuous—her inability to just say, ‘The End.’”

I think I’m drawn to this strain of Fichandler’s thinking, and the note of unmistakable pathos in it, not only because it seems abundantly clear that a questing, never-settled spirit was central to her forward-driving leadership, but because the theatre field she helped create is currently going through yet another rolling existential crisis, with contracting audiences, declining funding, widespread leadership turnover, and overdue but contested programs of diversity and equity. As many crucial lessons as these books contain about company-building and decision-making from one of the best who ever did it, they are possibly even more instructive on matters of company-sustaining, rethinking, regrouping, learning from failure, grounded in a strong connection to the ancient human roots of why and how we gather to tell stories in the first place. What would Zelda do? is a question very much worth asking now. These two books, read individually—or, as I did, in tandem—provide an abundance of answers.

Among her other striking qualities, Fichandler was searingly prescient—or, to put it another way, she was ever alert to the afflictions that perennially plague the lively arts. Consider “Hard Times for High Arts,” a speech she gave in the early 1990s, when recessionary pressures were forcing theatres to close, federal funding was in more or less permanent retreat, audiences were declining, artists were leaving the industry, the religious right was on the march against free expression—sound familiar? But it’s not just her diagnoses but her prescriptions that seem to point the way to our current moment: Rather than retreat into either the elitist or populist postures favored by some of her contemporaries, she full-throatedly advocates diversity and equity as central to theatre’s future (not least for their aesthetic and cultural benefits), and she sees robust arts education as a prerequisite for both a healthy civilization and a responsive audience.

Or look to “Whither (or Wither) Art?,” her spirited 2003 response to a series of provocative essays in this magazine, including Jaan Whitehead’s critique of stultifying “institutional art” and Todd London’s lament about the painful chasm between artists and institutions. Reflecting back on the lessons of Arena’s early years and the fieldwide struggles of the succeeding decades, Fichandler clearly recognizes in these voices a familiar call to create artistic sanctuaries from an extractive job-to-job economy—indeed, it was largely this impulse, in contrast to the “one-shot” Broadway model, around which Arena and like-minded theatres were founded. While she first mounts a partial defense of the regional theatre’s record as a talent incubator and culture creator, and issues her share of cautionary wisdom about windy idealism in the face of material challenges, she is ultimately not defensive. Instead, she ends up conceding the point that, yes, artists should get higher pay and an increased say on theatre boards and staffs, and that more theatres should be run by playwrights.

In fact, when she wrote that, the playwright and director Emily Mann was already leading the McCarter Theatre Center (and would be followed by other playwright-leaders like Chay Yew at Victory Gardens, Kwame Kwei-Armah at Baltimore Center Stage, and Hana Sharif, Arena’s current artistic director). But acknowledgment of her successors wasn’t always Fichandler’s strongest suit, especially if they were women. Indeed, Mann appears in the pages of Robinson’s To Repair the World as one of many women leaders who honor Fichandler’s path-breaking example on the one hand, and lament her failure to lift up the next generation of women on the other. As Mann puts it bluntly, “She was not a friend [to women directors]…She did not want any peers,” though she adds that Fichandler’s praise for Mann’s play Execution of Justice “meant a great deal to me.”

Robinson’s bracingly frank book is full of this kind of complication and texture: praise tempered by criticism, and vice versa. In one paragraph an actor will testify to the life-changing opportunity Zelda gave them, and in the next will starkly, sometimes bitterly, recount their falling out (and sometimes, though not always, weigh an invite to work together again). From a series of alternately harrowing and hilarious backstage tales, triumphs and setbacks, a portrait emerges of a glamorous, inspiring leader with exacting standards and a seemingly innate genius for seizing the reins and setting the agenda: in the rehearsal room, the boardroom, and later the classroom. This was coupled with a closely guarded vulnerability and self-doubt that would sometimes surface in her work as a director and as an essayist, but which Fichandler would not admit as an impediment to her work.

Some of those doubts arose from her role as a woman leader with children, and the impossible bind of the sexist expectation that she would somehow juggle these responsibilities without complaint, which never dogged her male colleagues. While she later confessed to friends that she wished she had spent more time with her family, she had always felt that her work was worth some sacrifice on the home front.

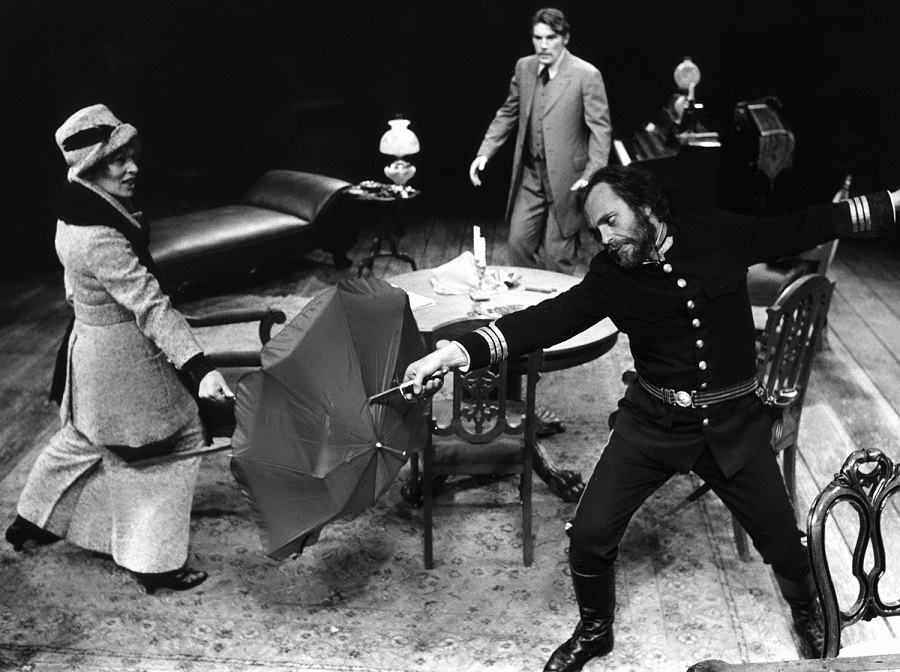

The most dramatic chapters of To Repair the World concern her struggles to hold together another kind of family: the acting company that was Arena Stage’s central attraction for decades, through which passed the likes of James Earl Jones, George Grizzard, Jane Alexander, Robert Prosky, Frances Sternhagen, Melinda Dillon, Roy Scheider, Rene Auberjonois, and Ned Beatty, among many others. Anyone who idealizes the storied early years of the regional theatre, when institutions like Arena or the Guthrie or Trinity Rep employed resident acting companies doing repertory work, should read these passages carefully. Can a standing company achieve a uniquely lived-in ensemble synergy onstage, a la Moscow Art Theatre? Sure—but for every such triumph (1974’s transcendent Death of a Salesman, starring Prosky, shines in most memories as a particular highlight), Robinson’s book recounts dozens of tense meetings, competitive struggles for creative agency, and enduring grudges. It becomes clear that as tough and uncompromising as Zelda could be, and as much as she put actors at the center of her theatre—literally and otherwise—it took an immense toll on her to carry “so many souls that you are attached to,” as she put it to a colleague.

That may explain why, when she became head of NYU’s graduate acting program, she seemed to feel somewhat liberated, since the job of an educator is not attach herself to souls but to equip them to soar to the next aerie. Though she had devoted the lion’s share of her career to building what she called, in the long, breathtaking essay that opens The Long Revolution, “Institution-as-Artwork” (her successor at Arena, Douglas Wager, said she “dramaturged the institution”), Fichandler was finally more at home inspiring than hiring and firing. The testimonies of the actors who thrilled to her annual speeches and blossomed under her tutelage—including Rainn Wilson, Mahershala Ali, Karen Pittman, Danai Gurira, Angel Desai, and Corey Stoll—are nearly universally awestruck and grateful.

At an evening earlier this year at NYU’s African Grove Theatre, celebrating Fichandler’s centennial as well as the release of these two new books, many of the actors whose lives she’d helped to shape, from Jane Alexnder to Randy Danson to Miriam Silverman, read their testimonies and/or speeches by Zelda, and a few acted scenes from plays that were especially meaningful to her (Uncle Vanya, Awake and Sing!). As Maggie Siff puts it:

Zelda was really important…in terms of defining purpose, making yourself believe you had a purpose as an actor. We get a lot of messaging as young actors that what you do isn’t a real art form. It wasn’t until I heard her speak that I could give language to this deep feeling I had inside that what I was doing, what I wanted to do, had a very important role in society.

Even in the NYU chapters, though, Robinson’s oral history pulls no punches, detailing a dust-up in 1992 when Black actors in the program vocally objected to Fichandler’s attempt to give them roles by programming a play about slavery, Carlyle Brown’s Yellow Moon Rising. Victor Williams, on hand for the NYU celebration, recalled clashing with Fichandler on this issue and learning, as he puts it in Robinson’s book:

There is no perfect first time around…[Zelda] was always proactive and assertive in trying to be at the forefront…I think the reality is sometimes she hit the nail on the head, sometimes she didn’t…You’re not always going to be on the same page in terms of how to get there, but you’re still on the same path.

That seems a fair summation. Directionally, Fichandler, like Joseph Papp, was raised with left-wing politics and remained more or less firmly on the side of the angels (“to repair the world” is the common translation of the Talmud’s “tikkun olam”). When it opened in 1949, Arena Stage was the only racially integrated theatre in Washington, D.C. And while she struggled fitfully to diversify her acting company, programming, and audience, in a city she recognized was predominantly Black, one of her final legacies at Arena was to establish the Allen Lee Hughes Fellowship, a career development program for theatre professionals of color, named for the theatre’s Black lighting designer.

By the time she had a stint running the peripatetic troupe the Acting Company, in the early 1990s, multicultural casting was enough the norm that the ensemble was only about half white. As she put it: “The subliminal message of this company was, we can make a world this way. We didn’t preach it. We didn’t say it. But there was a vision of it in front of them.”

Show, don’t tell, is as good a theatre motto as any. As these books demonstrate, though, Zelda Fichandler could tell with the best of them. Her arguments have a persuasive shape and rhythm, but she also had a near-Wildean gift for paradox (“Progress is a snail that jumps,” “We must hang on to our despair. Without despair, everything is hopeless,” “I know too much about it really to know anything”) and a pithy, aphoristic streak. Some favorites:

Success is always an accident, only failure can be counted on.

A mind, once stretched, never returns to its original dimensions.

Imagination is the nose of the public: By this, at any time, it may be quietly led.

A theatre gets the audience it signals to and deserves, and repertory is destiny.

Be a genius. If you aren’t a genius, try harder.

Risk-taking is not a line item in the budget but a style, an attitude toward living.

The basic law of [acting] technique is that something inside of us is always in motion.

Movingly, after ranging across the decades, The Long Revolution closes with her 1959 manifesto for the Arena, written at a time when the theatre she had founded 10 years earlier, somewhat capriciously, with her husband, Thomas Fichandler, had established a track record and a loyal audience, and was poised to move into a new home and become a Ford Foundation-funded nonprofit. It was a pivot point into a heady new era, and Zelda Fichandler boldly staked her claim to “A Permanent Classical Repertory Theater in the Nation’s Capital,” writing:

The art of theatre, whose true function for over two thousand years of human history has been the interpretation of man to man, has dwindled in contemporary America into nothing more significant than a “night on the town,” or a method of achieving prestige by having seen approval-stamped bits…The answer to the dilemma of the art of theatre in this country is simple and readily turned into a practical, living reality: We must create more theatre that, as Brooks Atkinson says, “is not so much show business as a form of culture.”

She also writes, in this prehistoric dawn of the regional theatre scene we now take for granted at our peril, of the intrinsic value of the resident model: “The permanent acting company is the actor’s best friend. It is also the audience’s best friend.” There’s that word again: “permanent.” Zelda lived long enough to witness the brittleness of that notion—not only the inherent fragility and insecurity of nonprofit performing arts but, perhaps more terrible, its zombie durability in a diminished, corporatized, quasi-commercial form. Writing in 1978, with a bit more hard-won wisdom under her belt, she gave a typically clear-eyed assessment of what the field she’d help found had accomplished, but could not, should not rest on:

We set out to create a form for theatre that would enable us to insert meaning and beauty into our culture so that people could reach out and touch it simply and directly. Despite hazards and harassments, we have in our various ways done just that. Our greatest achievement has been to decentralize or make “popular”—that is, part of the lives of people all over the country—the art of the theatre. It is a miracle of sorts. For not only did we have to construct the method to carry our idea, but we had to train an audience to know that they wanted to have what we wanted to give them. And that was not an easy struggle. It still goes on.

Indeed it does. When her successor, Doug Wager, visited Zelda in her final weeks, he said he told her, “We’re so lucky that we had the opportunity to transform the lives of so many thousands of people.” Zelda’s response haunts me, as it rightly should all of us: “No, no! More!”

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is editor-in-chief of American Theatre.