A baby and a theatre festival: Over a decade ago, a beloved Chicago couple discovered they were pregnant with both. Their kids now run about wild, creative, free. The annual Physical Theater Festival Chicago proved a popular tween this year, boasting eight different shows, five workshops, and three virtual events across the month of July, and attracting over 2,000 audience participants. But you may be surprised to learn that this landmark celebration of storytelling was conceived on an unassuming flight of fancy.

Co-founders and artistic directors Alice da Cunha and Marc Frost first met doing physical theatre in the U.K., and they continue to draw lifelong inspiration from sweeping curations like the London Mime Festival. “When we came to Chicago, Marc and I always said that when we retired, we would start a physical theatre festival,” said da Cunha. They didn’t have to wait that long, receiving a curatorial grant of $3,000 from Links Hall just two years into their Chicago residence—and three trimesters into the gestation of their firstborn, Benjamin.

If anyone can tackle such a massive undertaking, it’s these two brilliant creative leaders. Da Cunha and Frost have become local theatre celebrities, known for their warm effervescence and sharp critical eye for movement. Audiences crowd around them at each show for a conversation or a Carioca “hello” (two kisses on the cheek) as the two bustle about festival tasks. Their whole lives seem to have prepared them for these moments, as they switch seamlessly between community building and company management, diplomacy and art, heart and mind, one language and another. They extend many bridges.

Each year it’s moving to see how they form a border-defying family. Da Cunha’s roots in Portugal and Brazil and Frost’s upbringing in Chicago help them create Windy City spaces that feel like home to artists from all over the world. This year’s lineup featured much-anticipated spectacles which had garnered high renown in their home countries and accolades across international festivals. These included Clayton Nascimento’s grounded and transformative Macacos, from my native Brazil: Chula the Clown’s hilarious and heartbreaking Perhaps, Perhaps… Quizás from México; and an array of multigenerational offerings like cinematic The Man Who Thought He Knew Too Much from Voloz Collective (France/U.K.). From Chicago artists there was Scratch Night, featuring works-in-process; Theatre Y’s soul-stirring Little Carl; and an outdoor Millennium Park extravaganza with circus and magician performers.

All the pieces this year delved into some element of play, metatheatricality, and silent imagery. Many were one-person shows; some were completely nonverbal. All fit da Cunha and Frost’s expansive definition of physical theatre: “If you close your eyes, you wouldn’t get at least 50-90 percent of the storytelling.” Bodies in space morph into anything and everything: A child’s struggle to put on a jacket transforms them into a rhinoceros in the delightful Don’t Make Me Get Dressed (by Boston’s The Gottabees). In Macacos, a Black Brazilian man realizes the stage is a space to dream and resolves to become a jazz diva, until history bursts at the seams and floods in more sobering anecdotes. And in The Man Who Thought…, bodies turn into walls, bullets, horses, and spilled coffee, in the style of French movement artist Jacques Lecoq.

American performing arts often feel siloed. Genres like theatre, standup, circus, and clown self-segregate, and it’s not often you see a company deeply integrate those approaches and communities. This festival proves the value of intertwining international performance pedagogies. I felt the air shift with possibility each moment a performer broke the fourth wall, shifted genre midway through a show, ventured into self-referential territory, or pulled up audience members. Speaking with patrons, I learned that many look forward to the Physical Theater Festival each year because of this risk-taking innovation, which has become increasingly rare in a risk-averse American theatre landscape. People’s excitement around the international shows should be a lesson to Chicago, and more broadly the U.S., to continue branching out from conventional Western storytelling.

Take Perhaps, Perhaps…Quizás, for instance. This nonverbal one-woman show, which depends on audience participation, contains a degree of fourth-wall-breaking and engagement that is still all too rare in American theatre, and was executed impeccably in festival performances.

Dressed in a wedding gown, Chula the Clown starts out seated, penning love notes and romantic dreams on sheets of paper—then crumples them up. Her “mask”—a painted white face with arched brow—locates itself between the traditional 18th-century clown look and the 2010s boy brow makeup obsession. Hair sprouts from her head like an untamed wedding bouquet, moving with her as she jolts her head to notice the audience. She searches for a groom in the audience. Purses her heart-shaped lips and heaves a wordless sigh. Muchacha’s unimpressed.

Gaby Muñoz, the person behind the clown, has taken this particular piece around the world for 14 years, and has several other shows under her belt as Chula, who she describes as an extension of herself. Perhaps, Perhaps… Quizás has a heartwrenching ending you don’t see coming: As audience participants return to their seats, the protagonist realizes the extent of her loneliness, and, as Muñoz put it, her “absence of self-love.” Muñoz based this devastation on her own experience of separation from a longtime partner with whom she lived in London and Montreal. When she returned to Mexico City heartbroken, she didn’t know many people and decided the audience would become her playmates. “People are surprised with how much they can participate,” Muñoz said. “Audiences who don’t normally do theatre become a part of it. It’s vulnerable for me like it is for them, because I don’t know what will happen—I am not totally in control.”

She said she’s seen it all: At one performance a while back, a woman protested when Muñoz selected her boyfriend as the groom. But the ending is always the same, she said: We see the beloved protagonist restart the cycle of searching for love from the outside, never from within.

“The piece aims to lighten the theme, but it’s surreal how resonant it remains—trying to find your strength with someone else, when actually you must find it within yourself,” said Muñoz. “It’s been a form of therapy to me. I am a mirror to so many other stories like mine. I find community. I know I can feel deeply in silence, and still people can understand my pain.”

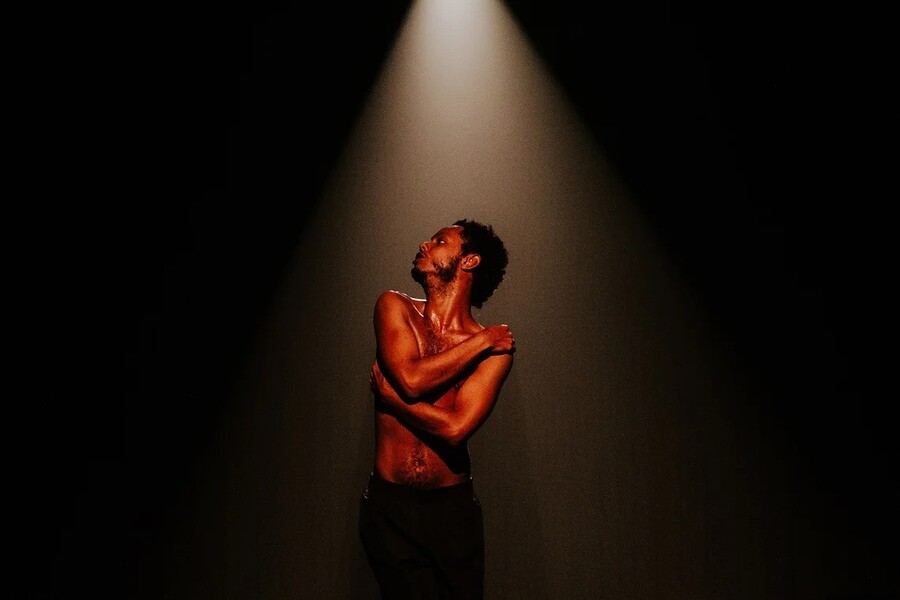

That balancing act between joy and pain also triumphed in Clayton Nascimento’s powerful Macacos. I’d long awaited this international sensation; several family friends in Rio de Janeiro had already seen the show, which has even impacted Brazilian justice and education. Nascimento’s central conceit, he said, is that “theatre is a space to dream,” and he makes full use of its possibilities, taking us through an embodied history crash course in Brazilian racism, recent murders of Black boys, and his own joyous dreams for more expansive and free living.

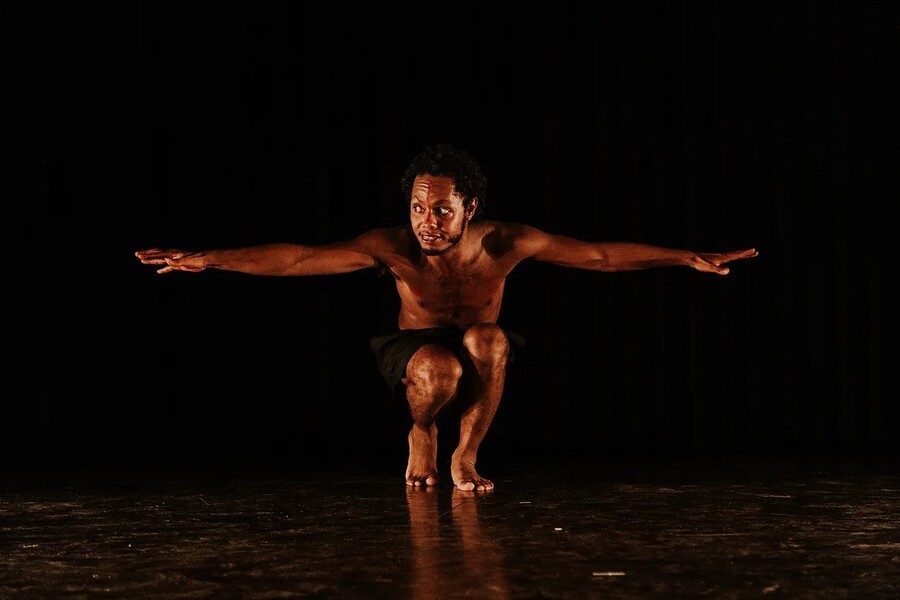

He begins the show in Brazilian Portuguese, with subtitles projected, contorting his body to depict white people hurling racist slurs, morphing into a Black child playing with a toy car, and relishing in the “Single Ladies” dance to emphasize Black joy. His body feels as poetic as his language, and watching him, I felt I was experiencing the genre of choreopoem afresh. Several minutes in, he stopped to address us in English, asking audiences members to share Chicago’s history of anti-Blackness.

At each place he tours, Nascimento modifies the show to suit that city, throwing in references and asking the audience to share their city’s realities. In Chicago the play ran 90 minutes, but in Brazil it often hits a sweeping three-hour mark, full of local references and a brave grappling together. This version for the U.S. aims to bridge the specificity of Black Brazilian experience with what international audiences may comprehend, offering more recognizable cultural touchstones, like novelist Machado de Assis, plus context about the U.S.’s own complicity in Brazilian oppression.

Beyond Nascimento’s tireless physical prowess and agile command of form, seamlessly moving us through different theatrical approaches, Macacos delivers its message and then some. Normally you can’t measure theatre’s impact on society, the way it shapes hearts and minds in mysterious and intangible ways. But Macacos has brought forth real-world justice: After one show in Rio, a lawyer approached him to reopen the case that is central to the show, in which police murdered 10-year-old Eduardo de Jesus Ferreira by his home. Now public schools in São Paulo plan to teach his script, aiming to fill a gap in education regarding Brazil’s history of colonial violence.

As the one-man show tours the world, Nascimento often brings along Eduardo’s mother, Terezinha. “The people have opened their arms to her,” he said. “Look at what the theatre was capable of.” She wasn’t able to come to Chicago for the Physical Theater Festival, but did provide a letter, addressed to her son, whom Nascimento embodied.

A spotlight of mourning focuses Nascimento, whose eyes fill with the tears of saudade. He speaks her words: “Clayton told me the stage was a space to dream. So I’m going to dream with you, my son.”

Macacos will next travel to Russia. I become misty-eyed thinking of all the places the Physical Theater Festival artists see, all the lessons they carry, all the stories they exchange, all the people they touch. Nascimento expressed his excitement about breaking the fourth wall, yearning to dream together with people from all over. Brazil poses its own tremendous challenges in conversations about race, and if Nascimento’s play could impact people’s lives there, well—I cannot deny that anything is possible. Hearing stories like Nascimento’s puts the world in context: Theatre has treaded upon dreamlike surfaces. It is only logical to expect more transformation to come from cultural exchanges, more than we could dare imagine now.

Said Nascimento, “Terezinha’s voice in the play stands in for many mothers who lost their children to violence. She becomes like all the mothers in the world. And every time this play happens, this mother can speak with her child. I have seen Terezinha along the years. And with each performance the play has allowed her heart to find more hope and see the world. The message I want to give people is: Dream.”

Even at workshops it was clear that dreaming at the Physical Theatre Festival means a great deal to Chicago residents beyond your average theatre artist. In a workshop called “The Clown and the Silence,” led by Gaby Muñoz, one participant said she didn’t have a background in theatre at all. What brought her there? “A retired lawyer needs a lot of clown,” she said with a laughing sigh.

As Muñoz put it, opportunities to play allow you to “viajar sin viajar.” Work across the festival transcends borders and ignites the human spirit, sometimes without language, always physically clear, and ever genre-bending. “I think a lot of people don’t know of the option to make theatre that way,” said Alice da Cunha.

She and Frost know they’ve done it again when they sit at the back of a theatre and listen to the audience. “That’s the most important part,” said Frost. “Listening to the audience.”

So I let the laughter and cries wash over me. The chatter in the lobbies invited me into a kind of family. Attendees who’ve been with the festival from day one mixed with those who had just fallen in love that day. Kids laughed with grandparents. Strangers speaking different languages felt familiar to one another because they’d experienced emotions through plays together, in their bodies. This sticky Chicago July, the globe seemed to move just a bit closer together.

Gabriela Furtado Coutinho (she/her) is American Theatre’s Chicago associate editor.