The death of Philip Arnoult at the age of 83 on June 30 sent shock waves around the world. Through his Center for International Theatre Development (CITD), Arnoult embraced the world. A cliché, the kind I usually seek to avoid, suggests that the world was a better place for his having been in it. In regards to Philip, that is no cliché: It is a mere statement of fact. This harsh, suffering world is infinitely better for Philip’s having lived in it. He pushed back at its complacencies, its shortcomings, its injustices, and its frequent cruelty for well over half a century, making dents and leaving marks with almost every shove. Philip’s work enriched, uplifted, enhanced, altered, bolstered, improved, and gave purpose and focus to the work of hundreds of thousands of people, if not even more. Most of those individuals, though not every one, was a theatremaker.

Philip, who many of us foolishly assumed was eternal, died having outlived his beloved wife, Carol Baish, by just 59 days. They married on Dec. 30, 1974. For Carol’s obituary in the Baltimore Sun, Philip said, “Carol was the love of my life. We were married for over 50 years. She wasn’t only my wife, she was my professional partner.”

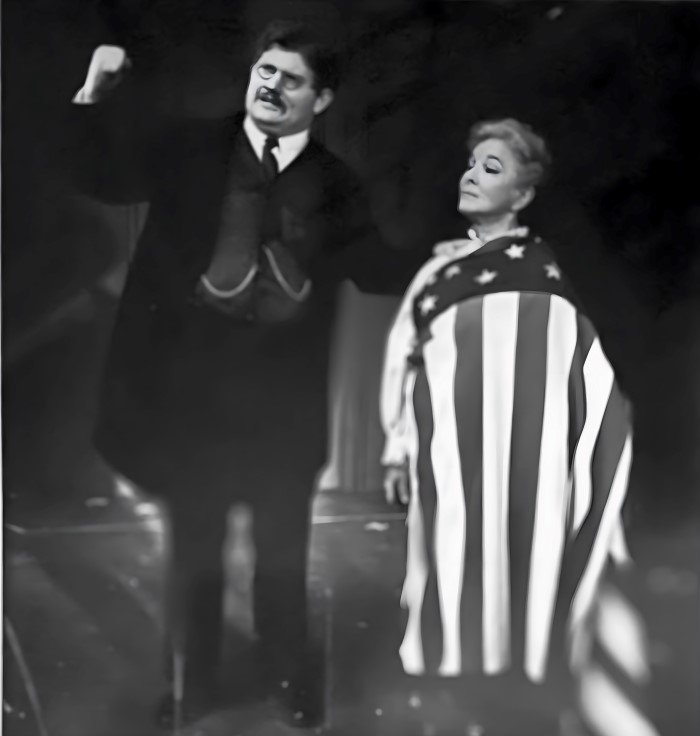

Philip took his first steps in theatre as an actor, a powerful one by all accounts. While still a student at Catholic University in 1964, he played Theodore Roosevelt opposite the legendary Helen Hayes in a short student run of William Cleery’s Good Morning, Miss Dove. Philip created his own theatre, the famed Theater Project in Baltimore (1971-1990), where he directed and became a producer and presenter, curating the influential New Theatre (1976) and Theater of Nations (1986) festivals.

Ultimately, though, he turned a corner to meet his true destiny, for at heart Philip was a people genius. Founding CITD in 1991, he became what Robert Avila called “a bounding impresario and advocate of new theatre” in a 2013 feature for AT. In the same piece, Philip toyed with the French term animateur as a self-description, then settled on “connector.”

Here is the essence of that: Philip saw in people the dreams they have of and for themselves. His dream was to make everyone’s dreams come true. A dreamer, and a man of great inner strength and conviction, he was opinionated and could be stubborn. He had the gift of a visionary, and his spiritual generosity was unbounded. Anne Bogart, in a group letter circulated among CITD alumni, put it this way: “Philip broke the proverbial mold, and because of that he created new venues and modes of communication for artists that never existed beforehand. He insisted that we cooperate and enjoy fruitful exchanges.”

Philip and I worked together on projects small and large, primarily a dozen Russian Case projects during Golden Mask festivals in Moscow, 2002-2014; the Russian Season at Towson University, 2008-2010; the New American Plays for Russia project, 2010-2015; and, most recently, the Ukraine Initiative, which grew out of my own Worldwide Ukrainian Play Readings, 2022-present. In all of these, passion was the common element, the driving notion. If we had passion for it, it was worth our doing. If the artists around were passionate about their art, they were the ones we wanted to work with.

Passion, that great mover of virtually everything human, has its dangers too. Philip could drive me—and not only me—crazy. I am thoroughly amused to see so many of Philip’s best friends admit in their loving testimonials to experiencing something similar. A time or two Philip and I set off on divergent paths. But the important thing, the lasting thing, the real thing, is that we always came back together, no matter what. Our friendship never bore lasting scars from those little detours.

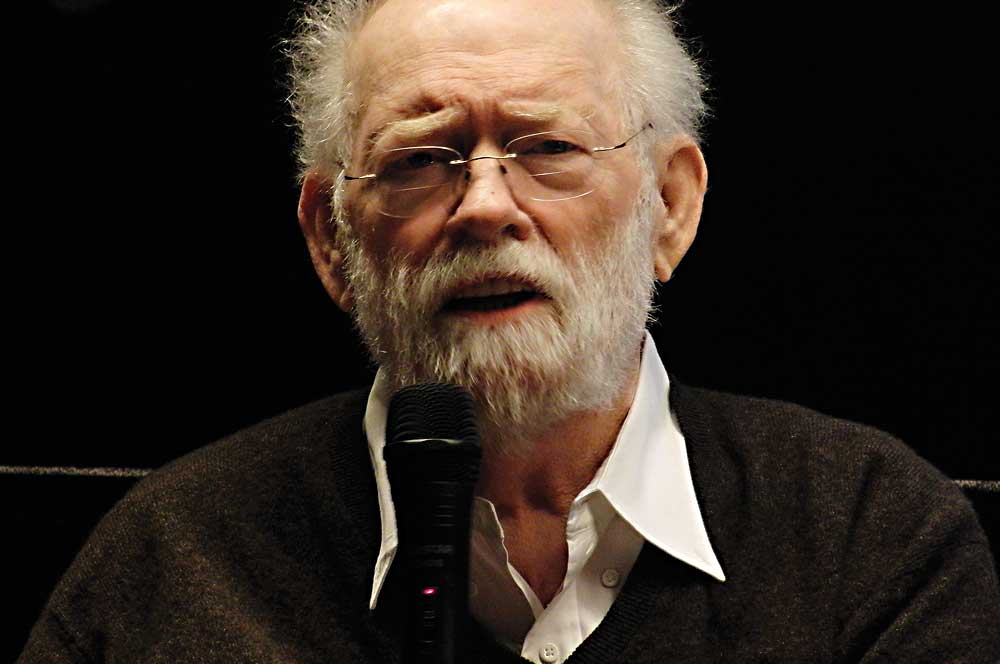

With hundreds, thousands of others, I too can say: Philip Arnoult changed my life. Philip gave my work a context and a mission that it lacked before I encountered him. He sought me out, probably in April 2001, during the Russian Case segment of the Golden Mask festival in Moscow. At that point I had been the theatre critic for The Moscow Times for a decade and had published a handful of books that few people knew, Philip included. He had summoned me, as he had a way of doing with people he was seeking out, and was waiting for me, looking rather regal, in the second-floor foyer of the Russian Theater Union on Tverskoi Boulevard. His omnipresent cap in place on his head, his trademark shoulder briefcase beside him on the floor, and his eternal windbreaker tossed over the arm of a plush easy chair, he shined on me what actress Sarah Olmsted Thomas called in that CITD group letter “his signature 1,000-watt smile.” I was comfortable with him immediately. We bonded as men with beards will do (although that’s not a guarantee).

Aside from his telling that he had seen Elvis Presley zip through Memphis on his motorcycle with Ann-Margret when he was a teenager (more bonding happening at breakneck speed), I don’t remember specifically what we talked about that day. That is so very Philip: The filler is the spice and the pleasure of the making of the deal. There’s a reason why, remembering Philip on Facebook, Jim Nicola recalls sharing “bowls of sour cherry soup,” before adding, “Rest well, and know you changed the course of history.” Because history can wait; hunger cannot. And with partners the caliber of Mr. Nicola, who needed to worry about the work getting done? The variable was the food, the drink, and the repartee you would share. Anyone who worked with Philip knows that the hard business end of the deal was something you relegated to the last 15 minutes of a sprawling, far-ranging, three-hour lunch-running-into-dinner meeting. Philip loved to talk. He loved to listen to people talk. He loved diversions, surprises, and non sequiturs, for he knew well that they are the stuff of life and art. He almost always had a kind of satisfied grin on his face as conversations careened from here to there, as if to say, “Damn, this is good! This is what I want to hear! Now listen to this!”

This is no superfluous retelling of pointless detail. It is a glimpse into the working method of a master at getting the most out of human resources. On Facebook, the American-born British director Noah Birksted-Breen wrote about Philip: “He told me once that his whole philosophy as a theatre producer was (paraphrasing): I just bring two good people together and then sit back and watch the magic happen.” That’s it right there. That 1,000-watt smile is what you would see when the magic was happening. Noah added this salient point: “What he really did was to think, and act, like no other theatre producer (none that I ever met, anyway). Not based on commercial considerations, but because he wanted to see what happens when different cultures meet. Fostering real world experiments. Creative, slightly anarchic. Brilliant.”

The Hungarian actor and director Martin Boross addressed Philip directly in his Facebook remembrance, wondering, “How it is even possible to be a deeply rooted part of so many other people’s lives with only one body and one life? How were you able to become family, friend, and mentor to so many people?”

That was Philip’s own magic. Philip loved every country he ever visited. In Poland he was Polish. In Slovakia he was Slovakian. (He was so impressed with Bratislava the first time we were there that he suggested opening a local CITD office that I would man—one project that didn’t get very far.) In the Netherlands he was Dutch. I was never with him in Africa, but I have no doubt that when he was promoting Russian contemporary dance in Kenya by way of major grants from the Ford Foundation, he was Kenyan. He loved all countries and all people equally, though his love for Hungary and Hungarians was a little more equal. That said, equality was a staple of his vision. As Sandy Timmerman, a founding member of q-Staff Theatre in Albuquerque, put it on social media, “He was a generous soul, he changed my life and he was my friend. In 1996 he took me to Hungary and introduced me to some of the best theatre I’d ever seen in my life. Then in 1997 he took me to Baltimore and introduced me to Double Edge Theatre and changed my life. Then he took me to Bulgaria, then he took me back to Baltimore, then he introduced me to Stereo Akt and changed my life.”

Philip was behind the making of so much theatre, I doubt anyone will ever chronicle it all. Famously, he was the first to bring a Jerzy Grotowski production to the United States. He was a moving force behind the American debuts of major European directors such as Ivo van Hove, János Szász, Kama Ginkas, Włodzimierz Staniewski, Jarosław Fret, and Krystian Lupa. He brought Russian director Yury Urnov, now associate director of CITD and one of the artistic directors of the Tony-winning Wilma Theatre in Philadelphia, to the United States. He facilitated the relationship between Edward Albee and Bulgarian director Javor Gardev, leading to the latter’s stage rendering of The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?, one of the most storied productions in recent decades at the Bulgarian National Theater.

In dramatic fashion, within weeks after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Philip took a fledgling Kyiv theatre under CITD’s wing, providing support to its 20 writers and numerous projects with generous grants, making possible the writing of new texts, the running of festivals, and the production of new plays. The Theater of Playwrights, as it is called, was founded collectively by a group of 20 dramatists, and was headed in its first two seasons by playwright Maksym Kurochkin. Upon receiving the news of Philip’s death, Maksym wrote, “Philip, a friend, is gone. Philip Arnoult came to my, and our, rescue right up to his last breath. He is forever now a part of all the good we will do.”

Forever a part of the good we will do. Doesn’t that sound like something that would apply to Philip Arnoult?

How many students transitioning into the theatre world’s workforce got their first job—or their dream job—thanks to Philip? How many actors, directors, and theatres were eager for Philip to see their new work because they knew he would never gaze upon them with a glazed eye or a cold nose? Brian Joyce, a member of the early U.S./Netherlands Touring & Exchange Project, recalls how, leaving a less-than-successful performance, Philip would say with that generosity of heart so characteristic of him, “Nobody sets out to do a bad piece of theatre.” How many of us, no matter where we are from, encountered people and art we would never have known were it not for Philip Arnoult and CITD?

I’m drawn to a comment made by Stephen R. Stern, who encountered Philip when he wasn’t even Philip yet: “Phil Arnoult was the first key U.S. partner of our Otrabanda Theater Company,” wrote Stern of the Ohio troupe. “[He] gave us a place to perform in the 1971-2 Theater Project early, ultimately weekly…a place to teach and a home base to tour from. He was very much the young hustler—effusive, abrasive; just what we needed for that year to solidify Otrabanad as an endeavor and to become an international company.”

From a young, effusive, abrasive hustler, onward and upward to what theatremaker Linda Chapman called “a unique leader who taught us how to shrink the world and think globally.” Wendy C. Goldberg, the longtime artistic director of the National Playwrights Conference at the Eugene O’Neill Center, put it succinctly: “Genius. Visionary. Into the wild. RIP Philip.”

And allow me to quote some rough-cut but eloquent words that Philip’s old friend Ari Roth, producer, playwright, director, and educator, posted for his own friends: “Passing on this news—heartbreaking on such a bittersweet day. Losing another giant. Rest in peace and inexhaustible curiosity. Travel hungry and with a ravenous appetite for talent, and daring, and challenging, and the new. Dear patron saint and pied piper heretic, such a good and nurturing man: Sir Philip Arnoult, you will be missed and always treasured. Much love.”

For the work Philip and I collaborated on, we were in touch by Zoom once a month over most of the last two years, and we emailed even more frequently. One recurring conversation came up virtually every time we talked, always with the same basic theme, although the words would be in different order. It arose because Philip and I both were devastated, furious, and confused when Vladimir Putin unleashed death and destruction on Ukraine. It disgraced and dishonored so much work we had done in, with, and for Russia. Philip would say, “This work in Ukraine feels more important than anything I’ve ever done.” I would respond each time, saying, perhaps, “It seems like the last 30 years have been preparation for this.” Philip might then say, “I think it’s the most valuable thing I’ve done,” and I would respond, “Yes, I feel that too.” Then Philip would take the conversation out of that loop by saying, “And I will be here to support them as long as it takes. As long as it takes.”

Indeed, the rest of us at CITD are here to carry on Philip’s work. For as long as it takes. For as long as it takes.

John Freedman worked with Philip Arnoult’s CITD (Center for International Theater Development) for nearly a quarter century. In that time he spent far more hours with Philip in restaurants and cafés than he did with his own mother. He is currently the project director for CITD’s Worldwide Ukrainian Play Readings.