I awaken on a foggy grey Saturday morning in New York City, an early spring day on which I have planned a double-header of Broadway shows. This kind of marathon would normally be an exciting indulgence for any theatre nerd. But as I prepare my coffee and stretch out my body, a nervous swell percolates in the pit of my chest. I’ve been working in theatre professionally as an actor, musician, and composer for over 25 years, and I have never attempted a two-show day quite like this one.

I’m furiously whirling a neon green fidget spinner around my calloused, nail-bitten fingers as the C train tunnels from Brooklyn into Manhattan en route to the midtown theatre district. In addition to being the only one on this subway car not looking down at their smartphone, I am a middle-aged man shamelessly fondling a toy made for coping with stress… you do what you gotta do.

I lean my body in the opposite direction of the train as it brakes to a stop. The momentary feeling of weightlessness caused by the momentum shift is a brief but therapeutic reprieve for my anxiety. I toggle forward as the C rolls into 42nd Street, and I think about how today, I will be attending previews of two separate theatre pieces I had a hand in developing, just before the pandemic; both of which opened on Broadway this season on the same weekend without me.

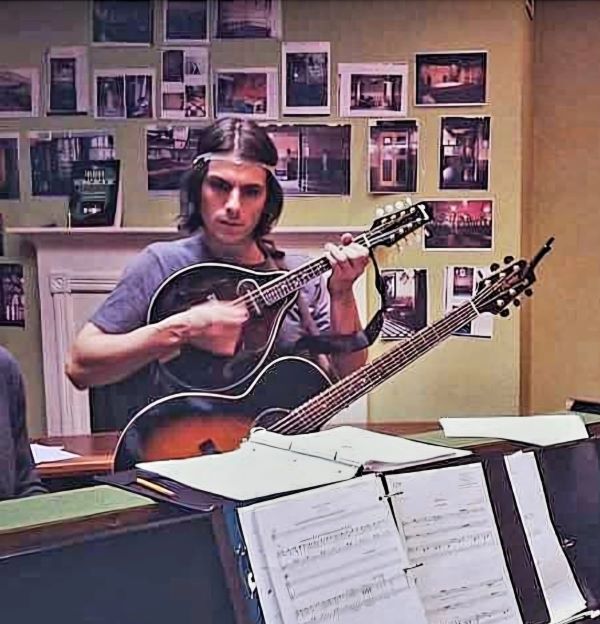

The Play With Music and The Jukebox Musical basically sit on opposite ends of the stylistic spectrum. Each had been in development for several years prior to my involvement as a performer. The Jukebox Musical is a fun, campy, traditional musical romp, with flashy choreography and trashy bits. I was cast as an actor-musician in its first full regional production in the fall of 2018, then participated in an extensive developmental workshop of the piece the following spring. Later that same year, in the fall of 2019, I was cast in an extensive developmental workshop of The Play With Music, an epic, intense, slice-of-life drama with a documentary-like feel and slow, moody musical jams. This workshop was to be its final stage of development before having an inaugural regional production the following year.

Extensive developmental workshops are the bittersweet fruit of acting jobs. You are essentially getting paid to help work on a new script and then present it to industry professionals, with virtually no guarantee of your own future involvement. Regardless of what stage of development they’re at or how well you fit in, as a participant in this kind of workshop you have to approach the process like you would any audition (albeit one that lasts anywhere from one to five weeks): Prepare your ass off, do your best, then let it go.

That’s often easier said than done. My track in The Jukebox Musical was fun and pretty low-stakes. I enjoyed being a part of it, but it was not as up my alley as The Play With Music, which as a performer I was practically custom-built for, in a way I am rarely built for any play. And this wasn’t just any play—this one was already causing quite a buzz in the new-play development circles. So the pressure was on, and the stakes were high, for me to do good work, and to prove myself worthy of eventually originating a juicy role in this great new theatrical event.

As far as I could tell, in early 2020, I would likely be moving on to the next phase of both projects—at least, I was never formally notified that I would not be moving forward with them, as other former fellow castmates in both projects had been. When the Covid shutdown happened, everything suddenly felt terrifyingly up-in-the-air, with a shroud of existential doom cast over the present and future state of the entertainment industry. Having these two potential opportunities sitting there in the ether gave me a sense of something to look forward to, especially at that time. If and when things went back to normal, I had some hope that I’d be able to pick up where I left off.

❦

The line is around the block for the matinee of The Play With Music, which takes place at the theatre next door to one where I worked for three years on my second Broadway production, a Best Musical Tony winner I helped originate back in the early 2010s. I see several familiar faces from that time still out there crushing it, eight shows a week—backstage, in the house, up in the booth—keeping the commercial theatre machine up and running. A check-in with these folks is comforting, in light of what I am about to put myself through: a firm reminder that, yes, I have played these stages and signed the Playbills, and have deftly dodged tourists on these crowded streets on the weekends to make it back in time for half-hour call to do it all over again, because It’s Saturday night on Brooaadwaaaaay!

There is a timeless and infectious feeling I get when I am participating in that system—a freight train I am drawn to hop and to stay on board at any cost. It is tempting to fall into the trap of seeing myself as a failure when I am not along for this ride and gainfully employed, which theoretically would mean I’m a failure more often than not. I learned pretty early on in my adult life that I was not built emotionally to withstand the lack of structure and security, or the constant ego-assault, of a career in the performing arts. But I was good at my craft, and I enjoyed the work when it came—which always seemed to happen just as I was about to walk away.

If you’re fortunate enough on this career path, you may get the opportunity to experience levels of rejection you had never dreamed possible.

All I ever wanted was to be a part, any part, of helping bring interesting dramatic and comedic narratives to life onstage or on screen—that is why I got into the business. I am fortunate to have played supporting roles in multiple projects that for me would earnestly constitute the phrase “living the dream.” But over time, I learned that the things that made me a desirable actor to work with in a professional capacity (grace, humility, selflessness) were often in competition with the things that made me successful in sustaining a professional acting career (ego, savvy, ambition). It remains tricky to find the right balance between those things, all while navigating the challenging and unpredictable waters that everyone is constantly trying to stay afloat in.

You hear the clichés about why dealing with rejection is a hard but necessary lesson of this life: about resilience, perseverance, backup plans, and thick skin. But if you’re fortunate enough on this career path, you may get the opportunity to experience levels of rejection you had never dreamed possible. In processing that rejection, when you can’t get answers, you try to rationalize it by looking in the mirror. I have all the stories I tell myself about why I am not cool enough, or attractive enough, or gifted enough—I dig myself into these deep, dark holes, traumatizing and denigrating my sense of self-worth, all to achieve some illusion of control so that I am numb to the haters’ hate when the outside enemy forces come for me.

The term “throwing toys out of the pram” is British vernacular for the times a baby or toddler throws their toys out of their carriage—i.e., an angry protest in the face of a relatively minor problem, essentially implying that the protester is acting like a baby. There were numerous situations and complicated emotions I encountered at the peak of my career that I would never in my wildest dreams have imagined I would come up against while I was “living the dream.” In the face of those challenges, I can recall multiple moments of throwing my toys out of frustration. I would lose patience with myself or with others, and engage in problem behaviors I am ashamed to divulge. In the process, my ability to be a good hang, and my reputation as a selfless, valuable ensemble member, kind of suffered. I was reprimanded. People close to me with whom I was working expressed their concern. I sought help, and I grew from the experience. At that point, I was seriously considering just getting out of the game, because I wasn’t having fun playing anymore.

I have settled into my seat in the lower mezzanine, and The Play With Music begins.

❦

The lights come up for intermission, and I head out onto the street, sneaking over to a back alley for some private reflection. I notice right away that I have a different sort of feeling in my body—a lightness I have not felt in months. It turns out that coming to see this show was…actually a good thing?!

For the past year, since the day I finally received confirmation that yes, The Play With Music was going to be produced, and no, I was not going to be involved, the feeling of rejection rented a room in my brain and caused a daily ruckus. I could not accept that I had come so close-but-no-cigar to something so great, that I was so right for. How the hell could I possibly bounce back from missing this opportunity? Each phase of the process taunted me, from hearing about those auditions and a whole new cast to the buzz-worthy Off-Broadway run, the rave reviews, the move to Broadway—my social media feed was making me crazy over this. I would hide Facebook ads and mute Instagram stories from friends, but it kept following me everywhere, even coming up in casual conversations with non-industry folks. I couldn’t get away!

Meanwhile the same thing was happening with The Jukebox Musical, whose most recent workshop I found out about from a former fellow cast member who texted me on the first day of rehearsal, wondering why I wasn’t in the room. That these two shows were unfolding this way in parallel with one another, all the way to opening on Broadway the same weekend—it felt like a sign. Maybe they were canceling each other out, and I was theoretically breaking even…I mean, even in the best-case scenario, I would have ultimately had to choose between them. But both shows? Two roles I am actually right for? I just couldn’t find a way to sit comfortably in my denial and avoid reality, no matter how hard I tried.

So I decided the only course of action to maintain my sanity would be to practice radical acceptance of the situation: by literally facing the music and going to experience both productions in one fell swoop.

It’s not hard to see how the approach to putting the right cast together for any project is akin to having the right puzzle pieces of a band come together.

I’m no casting director, but it’s not hard to see how the approach to putting the right cast together for any project is akin to having the right puzzle pieces of a band come together. It’s all about synergy, the different elements interacting and feeding off of one another, and the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. The Play With Music is literally about a rock band in the studio, recording an album; the cast is playing an actual band. And sometimes, even if you’ve got the killer chops or the right look or the flashy gear, your vibe just might not be the right element for the chemistry needed to make the music sound the way the composer intended. It all comes down to what is best for the song.

That seems so obvious when I spell it out, but it wouldn’t register in my brain in this context until I experienced it in the flesh. The chemistry among the cast of The Play With Music is undeniable up on that stage. They make a very good band. And as much as it stung to not be up there myself, I could recognize that the FOMO I was experiencing was more about me missing a great opportunity to be employed as a featured cog in a well-oiled machine, rather than me thinking I should have been a part of this particular cast. I honestly don’t know if I would have fit right. The actor playing the role I had done previously was excellent; I enjoyed their performance very much. (In fairness, I later learned that they too had participated in a developmental workshop of The Play With Music several years before me.)

Out on the sidewalk, I am spotted by a creative team member from down the street. I was trying to lay low, but they notice me right away, smile, and head toward me to say hello. I wrestle my ego down and am able to keep it securely bound and gagged as I genuinely compliment them on how good the music sounds and how successful the show is in creating a convincing portrait of a famous rock band, with performers who were mostly initially inexperienced playing musical instruments. It’s a testament to the audacity and the level of commitment of these talented actors, and to the power of theatre at its most collaborative.

As I head in for the second act, I think about certain moments during the developmental workshop of The Play With Music when I responded defensively to criticism or took a note as a sign of micro-managing mistrust. I think about times I may have seemed frustrated or perturbed in my problem-solving, or let the anxiety of deeply needing to be a part of the future of this project affect me, thus behaving in a way which would make it seem like I didn’t actually want to be a part of it. I try to consider what would be worse to find out: whether they moved on from me (or felt like I wouldn’t fit the chemistry) because I had a tendency to throw my toys…or because my work just wasn’t quite up to snuff.

But I realize that it might not be that black and white. Most things are not. And maybe that is the point.

❦

I head down the street to my old Saturday two-show-day hole-in-the-wall Mexican restaurant, by now overrun with the post-matinee swell, because apparently the food still checks all three boxes of being served fast, cheap, and delicious. I keep going around the block and climb into a booth at the trusty diner on Ninth Avenue. I feel proud for making it through the matinee clear-headed, and for gaining some perspective. I celebrate with a cheeseburger deluxe and a fine pilsner before heading back across Eighth Avenue for the second half of my marathon of rejection.

As I noted earlier, The Jukebox Musical couldn’t have been more different from The Play With Music. It is built around the songs of a legendary artist who was one of my formative musical influences from the early days of MTV, with an iconic voice and a slew of commercial radio hits. My personal function in The Jukebox Musical was more of a “special teams” kind of role: I sang and danced a little bit, but mainly I was on hand to induce a few laughs, shred some guitar, and get the hell out of there—and I was good with that. In the early stages of the 2018 production, upon first hearing me play guitar and belt a verse from one of his most famous songs, this legendary artist said (and I quote): “Oh, man, looks like we got a cat in the cast! And he sings just like me!” That moment was probably one of the low-key highlights of my career.

But I can also look back at my process in The Jukebox Musical and recall similar frustrations in response to criticism I’d had working on The Play With Music. I can attest to one specific display of throwing toys, in response to some working conditions I couldn’t believe were not union violations. I was proud to use my big mouth to speak up, to be the one from my cast to “represent,” but I could surely have done so more effectively. I later apologized and repented for my outburst. It was a public display I regretted, and behavior which belies the truth: that I do want to effectively solve problems, and I do want to be seen as someone who people want to work with.

As a veteran Local One stagehand once told me, after giving me the space to vent to them (in the same office underneath the stage their grandfather had once occupied): “Bro, nevah mind alla that. Ya go out there, do ya jawb, sing ya sawngs, go home. Ya got a great gig goin’ here! Ya wanna be out in Times Square playin’ ya guitar in ya friggin undawear like the Naked Cowboy?! C’mon, bro. Chill out, do ya jawb, fugghedaboutit.”

❦

As soon as the lights go down for this preview of The Jukebox Musical, I understand why I am no longer a part of this show: I may have aged out of my role, which is now being played by a performer of a completely different type than me. Also, the actors playing characters in a rock band are fake-playing their instruments. Perhaps the creative team actually did me a favor by correctly assuming that would have been a deal-breaker for me, even with a Broadway paycheck.

The FOMO of not being on board for the ride lingers, but I am able to enjoy The Jukebox Musical as the fun, silly romp of a show that it is and that its audience knows they’re coming for. It’s not trying to be “highbrow brilliant,” whereas The Play With Music just is. There has to be a place on Broadway for both kinds of shows, and the fact that I was able to span this spectrum while developing these two theatre pieces gives me a reason to fondly reflect upon the unique career I’ve had. After the curtain comes down, I head out onto the street and reconnect with several former fellow cast members, as well as a creative team member of The Jukebox Musical, who is elated to see me and grateful I came to show my support.

It’s so revealing what can emerge when we actively confront the thing that makes us crazy with suffering when it lives in our heads. It is easy for me to feel like a victim in these kinds of showbiz scenarios, or to beat myself up. But I chose this path, and it’s a hard road. When I’m able to leave my ego at the door, all I really want is to see audiences moved or entertained or having just experienced something close to magic, after spending their evening watching me and a bunch of other thespian freaks speak the speech and strum the tunes and bring a good story to life.

❦

I’m standing on the downtown-bound subway platform en route back home to Brooklyn. It’s almost past midnight, so there are no more express trains. Three consecutive useless E trains roll into the station before a packed C local finally makes its way down the tracks. Everyone is still on their phones, and my neon green fidget spinner is still whirling around in my hands, but perhaps a bit more slowly and steadily now.

I imagine myself trudging through the open desert, parched and sunburnt under the blanketing heat of a vast, inhospitable landscape, then suddenly receiving some assurance that there is a body of water up ahead. This undoubtedly helps motivate me along the rest of my journey; having an upcoming gig penciled in your calendar well in advance is the key to a sense of structure in the life of a performing artist. Sometimes I fantasize about what I would trade to ensure that there is always a body of water somewhere off in the distance. But in the end, what really matters is when you’re there at the water—when you’re riding the peak-hour train to get to rehearsal in the morning, or back home late at night after a two-show day. You uproot your life and move to another city for several months to get in a room with a group of people you mostly don’t know, who may have a whole different approach to their work, or a complete opposite temperament from you, and you’re now tasked with coming together and making a thing that ultimately only exists in a set place for a brief moment in time, and then…poof.

Don’t get me wrong: Usually it all works out for the best, and you have a powerful connection with a new group of artists who remain your show family for life, the bond being maintained through an epic text message thread that starts during rehearsal and continues long after the run ends. In some far-off dimension, the show goes on forever in your memory, and the people you made it with stay forever in your heart.

During the run of that Tony-winning musical I was a part of, I once had a realization, in relation to a specific onstage conflict I was having with another cast member. Rather than focusing on my own feelings of frustration, I needed instead to really consider the other person—to think about where they might be at, and what they might need—and to practice opposite action by taking steps in attempting to connect with them. It worked! It was effective not only in bridging the conflict, but in strengthening our connection onstage and off-. The show was better for it, as was my experience working on it.

I still have a way to go in terms of climbing my way out of the deep holes I’ve dug. I still find myself triggered by things that I thought I had gotten over. But if I ever make it back to the Great White Way (or any theatre space, for that matter), I vow here and now to place my toys gently on the ground, take a deep breath, and think of my show family and what is best for us as a whole—then go induce some laughs, shred some guitar, do my jawb, and get the hell out of there.

Lucas Papaelias (he/him) is an actor, musician, writer, composer, and experimental filmmaker. He has appeared on Broadway, developed and performed in many new (and old) plays Off-Broadway and regionally, composed musicals and theatrical rock operas, acted in feature films, independent films, television shows, web series, and played guitar in numerous rock and funk bands along the way. @lpfunkspix