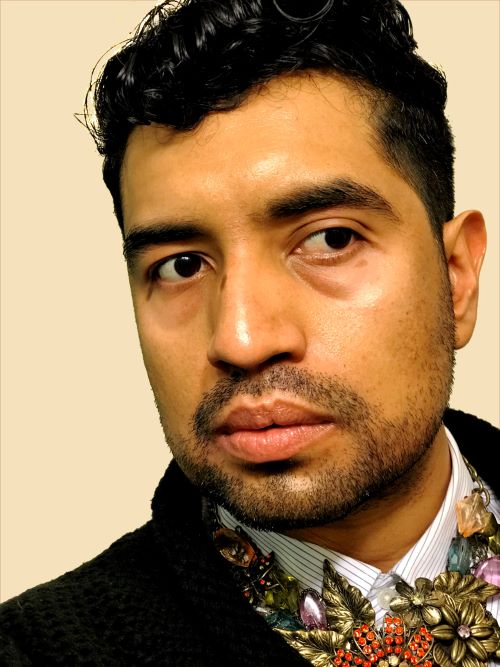

Late last year, playwright Victor I. Cazares made headlines when they presented an ultimatum to New York Theatre Workshop (NYTW): They would forgo their HIV medication unless and until the theatre called for a ceasefire in Gaza. Cazares was, until just prior to their strike, a resident playwright at NYTW through the Tow Foundation, and a teaching artist. Their announcement, bolstered by their frequent social media updates and performance art pieces about their medication, gathered widespread attention in the theatre community and a major profile in New York magazine.

Some artists, fans, and NYTW patrons supported Cazares, calling them brave; others saw their actions as narcissistic and criticized them for wasting the medication. (The Pulitzer-winning writer-composer Michael R. Jackson took to Twitter to call Cazares “nothing noble,” among other choice words.)

“I’m not asking for New York Theatre Workshop’s call for a ceasefire to be effective, right?” Cazares told me in February, when they were still on strike and their HIV had become detectable again. “That would be narcissistic.”

It felt impossible to get the questions of the moment out of my head when I first spoke with Cazares: Was there something else they could do with the medication instead of burning it or throwing it out? Did they think that a statement from NYTW would trigger a domino effect, encouraging other theatres to speak out? And what would Cazares say to people accusing them of centering their own suffering over that of Palestinians?

That last accusation is often hurled at protesters, including participants in recent uprisings and occupations on college campuses: that these events somehow steal focus from the atrocities they’re trying to highlight. But that, of course, is one of the points of a protest: to raise awareness and spark debate. That so many theatregoers and artists were debating the merits of Cazares’s direct action meant it was, on some level, a success. The whole point of protest is to redirect our attention, to make us think, indeed to make us mad. The premise that there is an approved way to protest is antithetical to its purpose.

“People say that my protest doesn’t make sense,” Cazares said. “But that statement doesn’t make sense—that feeling of, there’s a right way to protest and a wrong way to protest.”

Cazares hoped their medication strike would convince NYTW to call for a ceasefire because of their prior working relationship with the theatre and its staff. The theatre’s artistic director, Patricia McGregor—who started at the job in 2022, and who has repeatedly called for a ceasefire on her personal social media accounts—published a statement on NYTW’s website about the importance of making “embodied statements through the artists we support, the work we produce, and the audiences we invite.” That the statement did not mention Cazares or their protest was further proof to the playwright that their relationship with the theatre was perhaps irreparable.

“I don’t like to think about the fact that I was family to New York Theatre Workshop, and not a single one of them has messaged me or checked in on me, treated me like a human,” Cazares told me in February.

McGregor did reach out to Cazares in the intervening months. And some NYTW employees feel that the mistreatment went both ways, and that Cazares targeted workers and artists with whom they previously collaborated. McGregor and board president Jaye Chen said they never told staff not to speak to Cazares, but that many stopped reaching out regardless. Amid tensions at work, they said, many staffers were concerned that Cazares would broadcast personal text conversations on social media, as the playwright did in the first days of their strike.

This was even the case with some of NYTW’s community partners, including the National Queer Theater, who had their conversations with Cazares aired on social media. The National Queer Theater was among a handful of New York theatres to have publicly called for a ceasefire; in February, they put out a call to action for Gaza in partnership with Theatre of the Oppressed NYC, and have since offered support to local college students arrested for protesting and constructing campus encampments. But Cazares believes that NQT’s continuing ties to NYTW and to PEN America—a literary organization that has attracted widespread controversy for its response to the war and its handling of free speech claims by its Middle Eastern members—invalidate its call for a ceasefire. Cazares previously taught playwriting through PEN America’s DREAMing Out Loud, a free program run in partnership with NYTW and the National Queer Theater for undocumented and other immigrant playwrights. Cazares has claimed they were fired from teaching, a claim that both NYTW and NQT have disputed.

“I know there have been a variety of artists and community members that Victor has called out by name, and that the harm to members of our community has not been negligible,” McGregor told me. “We are trying to support and care for the artists and the community that surrounds us, and to do it in a way where we can listen to multiple perspectives in hard conversations, but without causing each other harm.”

McGregor pointed to NYTW’s offstage actions in support of Palestinian artists, as well as broader dialogue initiatives for both staff and the public. Online statements are only one part of the “toolkit” that institutions use to respond to a cultural moment, she said of NYTW’s workplace culture. “We often talk about the toolkit for response to the world.”

Some audience members and theatre workers may value an online statement as much or more than an offstage initiative, and McGregor said she respects this. She noted that in 2020, online statements about racism and police brutality were sometimes the only safe option for people who feared being infected with Covid or assaulted by police at large protests. Now, however, McGregor wants to use the stage to showcase NYTW’s values.

When I spoke to McGregor and Chen, NYTW had not yet announced their 2024-25 season, but they have since unveiled the lineup. Two of the three mainstage shows announced are by Middle Eastern artists: We Live in Cairo, about Egyptian student activists during the Arab Spring, by the Lazour brothers, and A Knock on the Roof by Khawla Ibraheem, a native of the Golan Heights whose credits include work with The Freedom Theatre in the West Bank.

NYTW has had a longstanding relationship with The Freedom Theatre (though some activists, including Cazares, believe there is a disparity between NYTW’s support for the Palestinian theatre and their refusal to call for a ceasefire). When multiple TFT members, including artistic director Ahmed Tobasi, were arrested by Israeli security forces conducting a raid on Jenin, the West Bank city and refugee camp where the theatre is based. Mustafa Sheta, Freedom Theatre’s general manager, remains in detention without charges. NYTW has been organizing for Sheta’s release, and McGregor noted that the theatre co-sponsored a March fundraiser for TFT in partnership with Noor Theatre, a MENA/SWANA company in residence at NYTW. Shortly after the arrests of Tobasi, Sheta, and TFT Performing Arts School graduate Jamal Abu Joas, McGregor spoke at a rally calling for their release.

“When the night falls, we sit in the dark. We don’t even have candles. We didn’t prepare for this,” Tobasi wrote in an email last month after the Israeli military raided Jenin and its refugee camp, killing 12 Palestinians, according to the Associated Press and Israeli news media. The Freedom Theatre regularly updates its website and social media with insights from artists and students, providing a living document of life in the West Bank. The theatre’s real-time archive may make the infighting in the New York theatre scene look quaint and irrelevant; others, however, may see The Freedom Theatre’s precarity as all the more reason to speak.

Despite challenges from some activists, then, NYTW has done a variety of “specific and actionable things,” including through season programming, to be “meaningful to the people who are most impacted,” according to McGregor. Still, I wondered: Why not make a statement calling for a ceasefire, after all this? The day we spoke, representatives from Hamas and the Israeli government were participating in ceasefire negotiations mediated by Egypt and Qatar; those talks later broke down concurrent with Israel’s intensified invasion of Rafah, a city on the border of Gaza and Egypt to which many Gazans have fled since October. A statement from NYTW at this moment would be far from radical.

Cazares ended their medication strike in April, on day 125. In an April 4 video on Instagram announcing the end of the strike, Cazares called out NYTW’s season programming and said it was “immoral to continue to work there” and “immoral to continue to be a subscriber.” NYTW is currently ending their season with Here There Are Blueberries, a Pulitzer Prize finalist from Tectonic Theater Project about the discovery of a photo album of SS officers and their families at Auschwitz. Though mostly rooted in the specific moment of the Holocaust, the piece ends with a generalized call to action against all genocide, noting that it “starts with words.”

In the beginning of my reporting process, I wondered if some people would dismiss the idea of looking to cultural institutions for statements on world issues, atrocious or otherwise. Some people may have read about Cazares’s strike and wondered why it mattered whether a theatre spoke about global politics. Is there anyone, let alone any government, who stands to change their politics based on a theatre’s public statement?

Perhaps this is the wrong framing. Che’Li, an actor and activist who has helped organize the grassroots Theater Workers for a Ceasefire and who recently staged a protest at a Florida theatre, does not necessarily call on the institutions they work for or associate with to take a particular stance. Instead they call on themselves and their colleagues to do so, whether the theatres they work with agree or not.

“That tension is where a lot of protest theatre lives,” Che’Li told me. “It’s the institutions that have the power and resources to put on stories, but ultimately it is the theatre workers within those institutions who are materially producing that work. [The theatres] are responsible for the means of production, but they do not own it.”

In February, Che’Li ended their performance as the lead actor in Lloyd Suh’s The Chinese Lady at American Stage in St. Petersburg, Fla., by revealing a keffiyeh underneath their costume. The scarf or headpiece, which has been associated with many Arab peoples and is a symbol of Palestinian resistance and liberation, was not part of the show’s costume design for the character Afong Moy. In the script, however, Moy, the first known Chinese woman or girl to emigrate to the U.S., perhaps by coercion, brings the audience up to the present.

“In the last scene, Afong Moy says, ‘I hope I have conveyed the relevance,’” Che’Li said. “She says this after she chronicles something like 50 to 100 years of anti-Chinese sentiment and violence, basically giving a history lesson. There was one performance in particular where I could not get through the last scene without sobbing. The images of all the atrocities happening in Gaza could not leave my mind.”

Che’Li and director Gregory Keng Strasser also decided to write “Free Palestine” on the actor’s chest; Che’Li included this phrase in their program bio, which American Stage producing artistic director Helen R. Murray asked them to change. In a statement to American Theatre, American Stage called the phrase “a slogan that has been appropriated from the Hamas mantra” (though the phrase predates the founding of Hamas).

“I just felt like I didn’t want to freeze this play in time,” Che’Li said of their action. In response, American Stage replaced them with an understudy for the remaining performances and issued a statement apologizing that their “stage was used to make a personal political statement beyond the scope of the art.” Che’Li said that their dismissal happened immediately, without mediation, while American Stage claimed that they held a conference call with everyone involved, though without a third party to serve as a mediator. Regardless, Che’Li, who stands by their actions, said they received widespread support from other artists and activists in the wake of the protest. Turning to colleagues with Theater Workers for a Ceasefire allowed them to channel their frustration into further action.

With the next theatre season looming, the violence and uncertainty of war remains the status quo. Much remains unknown, but we do know that tens of thousands of Palestinians are dead, bombed and burnt. We know that some Israeli hostages, perhaps long presumed dead, still cling to life. We know that despite endless horrific headlines, Palestinian and Israeli peace activists are putting their lives on the line to demand a ceasefire and a secure future.

What do we owe each other in moments like this? What do theatres owe artists, audiences, workers? It’s one thing to pose broad questions about breaking out of capitalist theatremaking models that rely on adherence to a given institution’s politics. We have asked these questions before. We have staged protest theatre and used the art form as a vehicle for change. When the musical Hair opened at the Public Theater in 1967, complete with characters burning their draft cards onstage, New York audiences welcomed the tribe with open arms; six months earlier, 300,00-400,000 of them had marched to the United Nations building with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to protest U.S. involvement in the war in Vietnam. Perhaps today, theatres are waiting for such a massive groundswell for Gaza, for peace, for dignity for all.

Or perhaps, as we wait, the violence and death becomes all too familiar. Despite a nagging voice, we become onlookers to a conflagration. Maybe you went to a ceasefire rally one day and began tech on a production the next, your energy now devoted to cast and crew. Maybe life got in the way of activism, a child got sick, a parent needed help, a friend you hadn’t seen in a year had something to tell you. Maybe your workplace isn’t as supportive of your politics as you thought it would be and you’re afraid of being unemployed in New York City as your rent and student loans weigh on you. Maybe the detractors are right and you genuinely don’t care.

Probably not. Maybe the reason doesn’t matter. Theatres in the U.S. may not be on the front lines of any war, but even dramatized conflicts onstage remind us that theatre is an embodied medium operating in a world at war.

As Cazares put it, “Theatre makes us confront these moments as real. It’s not theoretical.”

And what is protest, after all, if not a form of theatre?

Amelia Merrill (she/her) is a journalist, dramaturg, and playwright who is a contributing editor at this magazine. Her work can be read in 3Views, New York Theatre Guide, TheaterMania, and many more outlets. @ameliamerr_