Samm-Art Williams, a prolific playwright, actor, and producer best known for the play Home (currently having its first Broadway revival), as well as for roles as an actor and writer-producer on several popular TV shows, died on May 13. He was 78. Erich McMillan-McCall helped us create this tribute by Samm-Art’s colleagues and friends.

On May 13, the world bid farewell to Samuel Arthur Williams, better known as Samm-Art. A producer, writer, actor, and mentor whose legacy will continue to inspire future generations. As I reflect on my personal journey and the profound impact Samm-Art had on my life and career, it is clear that his contributions to the arts extend far beyond the stage and screen. I honor his memory and celebrate the indelible impression he left on all those fortunate enough to know him.

In 1978, I arrived in New York City from Chicago, a wide-eyed and eager newcomer. I had the extreme good fortune to be invited to join the acting company of the famed Negro Ensemble Company, which was both an exhilarating and daunting experience. I didn’t know anyone but was warmly embraced by the entire NEC family. Among them, Samm-Art stood out with his warmth and generosity, quickly becoming a friend and big brother figure to me.

Samm-Art was a gentle giant, a big man with a big heart. His physical presence was imposing, but it was his kindness and humility that truly defined him. He often referred to himself as “just a country boy.” He was raised in Burgaw, N.C., a small town that deeply influenced his life and work. His rural upbringing was a constant source of inspiration and permeated his trailblazing writing.

Samm was a formidable presence both on stage and off-. As an actor and playwright, he possessed an innate ability to capture the essence of the human experience. One of my fondest memories was acting alongside him in Gus Edwards’s play Old Phantoms, where we portrayed brother and sister. Samm was a very still, focused actor onstage, but full of fun and mischief in our offstage moments. We had a ball, and his joyous laughter remains etched in my memory.

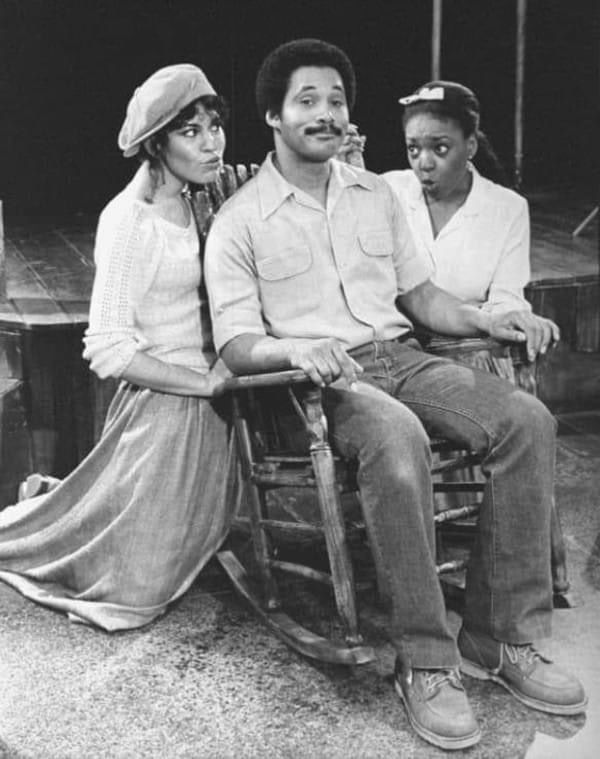

Of course, Samm’s most celebrated work, Home, holds a special place in my heart and career. I had the honor of reading it when it was still just poems and musings, later workshopping it along with Dean Irby, Charlie Brown, and Hattie Winston, and ultimately making my Broadway debut as Woman One/Patty Mae, along with Charlie Brown and Michele Shay (Woman Two), with Douglas Turner Ward directing.

Home is a powerful narrative about a young man’s journey from the rural South to urban America, exploring themes of identity and a search for belonging. Cephus Miles, the protagonist of Home, was imbued, not unlike Samm, with a Will Rogers-like storytelling charm, spinning his side-splitting tall tales, and along with Woman One and Woman Two (creating ALL the other characters in his life), wove a joyous world of love, laughter, and tears. Audiences and critics alike dubbed it a “cultural phenomenon.”

Performing in Home was the privilege of a lifetime, a labor of love beyond my wildest dreams. The play’s triumphant success, including Tony Award nominations, was a testament to Samm-Art’s extraordinary talent and vision.

After conquering the world of theatre, Samm-Art Williams expanded his horizons to Hollywood, where he made significant contributions as a producer, writer, and actor. Despite his success there, Samm’s heart remained tied to his roots. He was at heart a loner who found solace in solitude. Not surprisingly, he left the Hollywood glitz behind and returned to North Carolina to live, bringing his amazing journey full circle.

Remembering our times together, I am filled with gratitude and pride. Beyond his professional achievements, Samm was a beacon of light and mentor to many of us. He could always be counted on for guidance and words of wisdom. Once, when I was nursing a broken heart, he offered words that resonated deeply: “A broken heart is like a broken bone; it will heal stronger in the place where it was fractured.” Those words not only helped me through that tough time but became a guiding principle in both my life and art.

The passing of Samm-Art Williams is a profound loss, but his spirit rests with the ancestors, living on in the countless lives he touched and the rich body of work he leaves behind. His timeless plays will continue to be performed, studied, and cherished for generations to come. Indeed, the celebration of his extraordinary legacy continues with the Roundabout Theatre’s Broadway revival of Home, directed by Kenny Leon.

As God, finally back from Miami, would say, “Well done, my good and faithful servant.”

L. Scott Caldwell

Samm-Art Williams, a coon-chasing, possum-eating man from the backwoods of Burgaw, N.C., whose sense of humor came naturally, made you laugh in a heartbeat. This send-off is for you.

Samm and I met in New York at the Negro Ensemble Company. He was friends with one of the great loves of my life, Charlie Brown, who starred on Broadway as Cephus in Samm’s iconic play Home. He visited us often in our prewar apartment on 105th Street and talked regularly about his love for Burgaw, as well as his mother, friends, and the animals that haunted the back woods surrounding our bordering communities.

During those early days in New York, our commonality became overwhelmingly apparent: Burgaw is less than six miles from where I grew up, in Wallace, N.C. Samm-Art and I had both left the South to make names for ourselves in the Big City. A giant of a man with a teddy bear heart, Samm was shy and unassuming.

During the rehearsals for Home, his signature play, produced on Broadway by the Negro Ensemble Company and Liz McCann and Nell Nugent, I got to know him even better. Nightly, waiting for the show to start, we’d spend time backstage, him telling stories, me an avid listener and his captive audience. “Possum stew and fried coon” was our running joke. I don’t know if he ever ate either one, but he talked about them until I was on the floor rolling with laughter.

Home on Broadway was Samm’s story. He was and will always be Cephus. Always a down-home, easygoing person, Samm-Art would show up anywhere, any time, and any place as himself. What I loved about Samm is that he didn’t know or care to be anything but himself.

When we both found ourselves in California, I invited Samm to my birthday party, packed with celebrities, at the home of Lynn Whitfield. For our Mardi Gras-style celebration, guests were instructed to dress formally and bring a bottle of Moët & Chandon. Samm showed up in shorts, T-shirt, and tennis shoes with a bottle of MD 20/20, and was the life of the party. That was Samm.

When he got ready to return home to take care of his mother is the one and only time I have seen Samm serious. He said California was too big for him. He missed Burgaw, where he could just be Samm.

Once home, he jokingly claimed he couldn’t even go to the post office in Burgaw because all the “single ladies and widows had their sights set on him.” Said he ran so fast, he lost his shoes. Shared that he’d rather sit on the front porch, drinking moonshine and telling tall tales. I don’t even think Samm drank anything, much less moonshine.

He did, however, bring his Rolls-Royce home to Burgaw. Even though he had to drive over 50 miles for an oil change. He said that car was the only thing he had left from his Hollywood days.

Samm-Art Williams was always just a “country boy” at heart who had lived all his dreams and was now back home where he belonged. Rest in Peace, Samm. Hope you took some moonshine, possum stew, and fried coon with you for your trip. Please share some with St. Peter. He’ll be proud to let you into the Pearly Gates.

Lorey Hayes

My first job in New York City was with the Negro Ensemble Company, and I was hired to understudy Samuel L. Jackson on the Southern tour of the play Home by Samm-Art Williams after the play’s Broadway run. On that tour we had the opportunity to visit at Samm’s home in Burgaw, N.C. We met his family and broke bread at his home, but the true honor was sharing his storytelling with the rest of the world.

My roots are in rural Texas; I used to jokingly say to Samm that Burgaw “ain’t nothing but a suburb of Texas.” We were just two country boys telling stories—telling our stories with our specifics and trying to make art to change the world. That led to a number of opportunities with the Negro Ensemble Company in New York that also included stepping into his play Eyes of the American, when Glynn Turman, who originated the role, had to step away. I got to reprise that role in a Los Angeles production not long after that.

Samm was a mentor, but first he was a friend and a brother. His generosity and giving spirit and storytelling impacted the things I put on a page as a writer, and how I put them on a page—with confidence, truth, and clarity—and even more importantly why I put them on the page. His documentation of the human condition in all its strengths and weaknesses and challenges and successes inspired me to tell my stories and create work that would change the world.

What joy we found when we had the privilege of sharing the prowess of his storytelling with audiences in Southeast Asia on tour with the Negro Ensemble Company. Audiences in Bangkok, Hong Kong, and three cities in the Philippines, Malaysia, and Singapore got up off their feet and identified with Cephus Miles in his challenge-filled journey to the city and his return to himself back home.

Not long after that, in Los Angeles, when Samm was executive producer of television shows, he produced a new play of his titled Woman From the Town and asked me to create the role of Buddy alongside Roxie Roker, Denise Nicholas, and Loretta Devine. He mounted it at the Inner City Cultural Center in Los Angeles, and that year at the NAACP Awards I was honored with Best Actor, Roxy was honored, Loretta was honored, and the play won Best Play!

Time went along, and not long after that I was producing my first play, East Texas Hot Links, in Los Angeles. “Big Samm” came by a tech rehearsal and sat in. I noticed him writing something in the audience and thought he was going to give me some notes, but he walked up to me and said, “I don’t know what you need, but I hope this helps,” and he handed me a check—a personal check for $500. He didn’t just talk the talk; he walked the walk.

I shared every play I’ve written with him, and he never failed to call with notes and encouragement. The man was a mentor and friend and I am blessed and grateful and I will miss him forever.

Eugene Lee

Samm-Art Williams was without a doubt the best 6’6”, 300-pound playwright, screenwriter, actor, producer, director, and boxer to come out of Burgaw, N.C. He filled his massive frame with a talent that was boundless. I met Samm in the mid-’70s at the Negro Ensemble Company. He was an actor-playwright; I was an actor-director. NEC was a hotbed of activity at that time, with major productions on the mainstage; workshop and showcase productions in the tiny studio space on the third floor; classes in acting, dance, and playwriting throughout the building; and a scenic shop on the fourth floor. St. Marks Place and Second Avenue became the center of our universe.

It was there where we began to nurture our identities in the theatrical landscape. One of the first plays I was assigned to direct by Douglas Turner Ward (artistic director) and Steve Carter (writing workshop coordinator) was Samm’s Pathetique, an homage to his brief boxing career with the powerful Gil Lewis in the lead. Shortly after that we were linked together again with a workshop production of Welcome To Black River, set in his familiar countryside of North Carolina. With this show, Samm and I became close collaborators and created a production company, Black River Productions, with the goal of producing that play ourselves. The venture failed, but the experience cemented our relationship as a creative team.

In 1978 we came together to work on Samm’s signature opus, Home. This brilliant piece of theatre pulled together all of his literary gifts: his poetry, his art of storytelling, and his down-home articulation of Americana. What a joy to bring Home to life with Charlie Brown, Michele Shay, and L. Scott Caldwell in the original Off-Broadway production. I was not afforded the opportunity to move with the show to Broadway, but having participated in the structuring and staging of Home was a personal highlight of my career. It was a bittersweet ride, but I’m eternally grateful to have taken the trip.

Samm’s skills flourished when he moved to L.A. His well-documented stellar career was the result of the strong foundation built in the trenches of New York theatre, primarily NEC. We didn’t have much contact after his move, and I feel a hole in my heart that he left this plane with unresolved issues between him and me.

A couple of days before Samm’s transition, I ran into Kenny Leon in a restaurant. It was a few weeks before the opening of his production of Home at the Roundabout Theatre. We talked about Samm and he asked me about my approach to the play. I waxed about its musicality, lyricism, and other things that were surely obvious to him.

A couple of days later, on the evening of May 12, I had a long conversation about him with his dear friend Barbara Montgomery. She informed me he had just been placed in a nursing home. I was floored. I had no idea he was that ill. The next morning he was gone. It seems so remarkable that, after not being on my speed dial for so long, Samm was the subject of these two deep conversations about him. It was like a message was being sent. Like the frantic flurry of birds before a storm.

Samm-Art Williams was/is a force of nature, as evidenced by seeing this mountain of a man, dripping in sweat, jogging up Ninth Avenue, cars getting out of his way.

I will miss my friend and brother, but I’ve already missed him for a long time. All of life’s foibles fade away in the wake of true friendship. I hear you talking to me, Big Samm.

Welcome home, “Philadelphia Smoothie.”

A. Dean Irby

As a theatre producer, I am privileged to bring stories to the stage that unveil the tribulations and triumphs of Black life in America. As the founder of the Atlanta Black Theatre Festival, I have facilitated the production or staged readings of original works for more than 160 playwrights. It can be overwhelming to see how much work is worthy of production and how few reach the forefront of the American theatre.

The brilliant Samm-Art Williams stands out among these playwrights who have risen to the occasion. Born in Burgaw, N.C., in 1946, he grew into a statuesque (6’6”) but gentle man who loved poetry and words. With this physical stature, he could have easily become an athlete, and even tried his hand at basketball. It was also said he sparred with Muhammad Ali. But Williams followed his dreams and pursued a career in acting, producing, and writing. He struggled as a playwright initially and worked as an actor to help pay the bills.

Williams was known to write stories inspired by the characters he developed. He advised playwrights to focus on evolving characters before creating the story. Many of his stories were inspired by his own experience or members of his family, layered with authenticity and realistic complexities. His writing was profound, eloquent, and masterful. One common theme in his writing was the migration of Blacks from the desperation of Southern living toward the pursuit of civil liberties and economic opportunities in the North.

Though he wrote about the Black experience, he often touted his ability to write plays about any ethnic group because of his focus on his characters’ humanity rather than their racial identity. As an intuitive writer, he reflected a complete understanding of human nature. He expressed the importance of fleshing out the characters first and the story that would arise from those characters.

His most famous play, Home, was written in 1976 while he was riding a Greyhound bus to North Carolina. The ride inspired the characters, leading to this iconic work. Home was first produced on the stages of New York City’s Negro Ensemble Company in 1979 and made it to Broadway in 1980, garnering a Tony nomination. Home is a master class in playwriting, delicately weaving the rhythms and stories of life in New York City with a vibe that transcends generations. Though written in the ’70s, it speaks a language that penetrates beyond the surface, firmly rooted in realism. The setting of the story brilliantly reflects the flavors and textures of New York, with each character layered with their own story and one prevailing theme: their perceptions of home as an object of belonging.

The story is as relevant today as it was when it was written. Today’s generation is also grappling with themes of discovering and exploring a sense of community. In a world where globalization and digital connectivity bring us closer yet sometimes make us feel more isolated, searching for a place to call home resonates deeply. The play’s exploration of migration, identity, and the quest for personal freedom strikes a chord with contemporary audiences navigating their own journeys of self-discovery and belonging.

The show’s current Broadway revival, directed by Kenny Leon, began performances the same week as Samm’s passing, poignantly reminding us of the timeless and fragile nature of the human experience and our enduring quest for a place where one truly belongs. One might consider the revival of this iconic work a poetic, metaphorical message. As many in the Black community would say, “God has called our beloved Samm-Art Williams home.”

Toni Simmons Henson

Samm-Art Williams was an extraordinary man. Maya Angelou reminds us that people will forget what you said and what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel. Anyone who knew Samm didn’t forget what he said or did; we all knew how he made us feel.

I met Samm while a young student in the advance acting class at the Negro Ensemble Company, taught by Anderson Johnson. Samm was performing in Steve Carter’s Eden at NEC’s St. Mark’s Playhouse. Between Steve and Anderson, we were introduced. Samm was an imposing figure physically, but a gentle soul. As we shook hands, something brought a smile upon his face. In fact, he always had a laughing smile when we saw each other. Samm, along with the other seasoned artists, taught me by example to be supportive of those still learning. I recognized them as good people because they knew how to make young artists feel good in an intense industry.

In New York City in the ’70s and ’80s there was a supportive Black theatre community. Mentorship and a sense of family was evident. As a young actor, I was welcomed by Samm to pick his brain about the craft and business. I was delighted when Samm cast me in the New Federal Theatre production of Liberty Call which Samm directed and starred in.

As my focus turned toward directing, Samm’s advice was to always go with the intelligent actor—the one who had a clear thought process with landing actions and objectives. His advice has served me well to the present. Samm was a talented actor and brilliant playwright who always shared his experience and time with everyone. I appreciate his example of listening as an artist. His mentorship is one of my early treasures.

May he be remembered for what he said, what he did, and how he made us feel. Indeed, he was good people.

Prof. Dale Ricardo Shields

Archivist and theatre historian

There are people you don’t even know you’re looking for until you find them. Then you say to yourself, What took you so long? I found Samm-Art Williams at the theatre, the Cort Theatre, now renamed to honor James Earl Jones. Home was my first Broadway show. I had missed it at the Negro Ensemble Company the year before, and I was happy that director and NEC founder Douglas Turner Ward had found a way to move his production to Broadway. I had been longing to see it and now, at last, here I was, full of nervous apologies and great anticipation as I stepped carefully over people’s feet and settled in.

It was 1980 and I think it would be more than fair to say that at this point, my life was a hot mess, full of desperate longings and doomed love affairs, but that’s what your 30s are for, and besides, that’s not this story. This story is about a moment when suddenly none of that messiness mattered anymore. A moment when Samm-Art Williams showed me not simply what it meant to be a playwright, but what it meant to be a certain kind of playwright who always leads with great love.

It was the second most clarifying, satisfying blast of cultural possibilities that I had ever had—the first being my realization at age 12, after seeing the NEC touring company perform Raisin in the Sun in front of a sold-out Detroit crowd, that I wanted to be a playwright. I announced this revelation to my family on the ride home. “Then that’s what you should do,” my mother said, though she denied it later when I headed to Howard University to see if they could teach me how, and they did. But for me that time was all about wishin’, and hopin’, and thinkin’, and prayin’, like a sepia-toned Dusty Springfield. That extended Howard perfect moment was all about dreaming. But this New York City, Broadway moment was about doing.

When the lights went down in the beautiful Cort Theatre and young Cephus Miles, the central character in Home, stepped into the light at centerstage to share his story with us, I was transformed. I sat there listening, feeling, laughing, and crying right along with the other 1,049 people in that audience who were leaning forward in their seats just like I was, trying to get closer to what Samm-Art Williams was offering us. Trying to accept this gift. This isn’t just what I want to do, I thought. This is how I want to do it!

That was the magic that Samm-Art Williams’ Home created for all of us that night. That was the gift he offered me, as a young writer still feeling my way. The gift of a complex tale about complicated people who sounded as familiar as a barbershop story or a Motown melody. With just three actors, Williams created a whole world. He showed us not only how strong these characters were, but how fragile. Sure, they were courageous and resourceful in the face of everything their lives threw at them. Sure, they survived heartbreaks and betrayals, discoveries and rediscoveries. But the feeling I remember most clearly from that night is the fierce urgency of their joy. It was beautiful in its simplicity and undeniable in its truth.

By the time I rose to my feet with the rest of the audience for an ecstatic standing ovation, I didn’t just want to be a playwright any more. I wanted to be a passionate, unstoppable truth teller. And I wanted those truths to be so powerfully human, so real and full of love and hope and beauty that they could fill seats in little theatres and big theatres and, if the ancestors wanted it, Broadway theatres, too, because Samm-Art Williams had shown me that there was nobody’s gaze more powerful than his own. Nobody’s people more beautiful in the lights than his own.

He did a lot more wonderful writing after Home, a lot of acting and producing, creating and collaborating, and I’m always happy to see him in a film. He had the blessing of a long life, full of accolades and adventures, but I remain most grateful for that moment at my first Broadway show when the house lights went down and the stage lights came up and the genius of Samm-Art Williams brought me Home.

Pearl Cleage

Distinguished Artist in Residence

The Alliance Theatre

Home was on my summer reading list. I was steeped in research on Kenny Leon, the director at the helm of the play’s new Roundabout Theatre revival, for a project I am working on for the August Wilson Society. I knew of Samm-Art Williams’s work as a screenwriter, actor, and producer. His name was on the rolling credits for many of the popular television shows I watched when I was younger. I remember watching Motown Returns to the Apollo with my parents, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, episodes of 227 and Amen with my aunt and grandmother, Frank’s Place, and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air and Martin as a college student. I also knew that we both majored in psychology, that at one point we thought we would become lawyers, and that living in New York City was too isolating for both of us.

But at the time of Williams’s transition, Home was in previews and I had still not read the play. Before I wrote this tribute, I knew that reading Williams’s most seminal work had to be the first act of remembrance to honor the life and contributions of a humble and humorous man who believed that everyone in the county of his hometown of Burgaw, N.C., had a story to tell.

Come home. Come home.

The land sadly cries.

Come home from where you’ve all gone.

Children of the land. Babies of the soil.

As I read Home, I quickly came to understand not only the importance of the play in the Black theatre tradition, but also why the work has continued to engage audiences all over the world for the past 45 years. Within the lyrically expressed “sorrow and ecstasy” of Cephus’s experience and longing for the familiarity of his hometown are Africanist signatures and aesthetic values: the crossroads, the land as a sacred and transformative space for ritual, the structure of recalling and re-membering through migratory movement, the itinerant bluesman, the shapeshifting trickster figure, and the wise choral community. Williams’s elevation and reverence of the concept of home as seen in the play’s dedication, recalls an oft-repeated adage in Yoruba belief: “Heaven is home, but earth is the marketplace.” Burgaw—the crossroads at the center of Home—was Williams’s true heaven. It was a source of empowerment, treasured stories, and Southern values of hardiness, geniality, and gentleness. This was the world that Williams was always striving to return to as he navigated New York, Los Angeles, and the spaces in between.

The Yoruba also believe that “a river that forgets its source is destined to dry up, but a river that remembers its source will always flow with joy and abundance.” Williams’s reverence for the river that sustained him was evident in his life and work. However, like Cephus, as he noted in a 2010 Chicago Times interview, Williams felt he couldn’t go home until he achieved something. Thus, every career move and success between 1968, when he left for Morgan State College and 1998, when he returned to North Carolina, “was to get back home.” Upon his return, he moved into the guesthouse next door to his mother. A high school English teacher and drama director who cast him in shows she directed, Valdosia Williams played a key role in shaping the man whose pen, keystrokes, acting, and producing spun the tales that have moved us deeply. The formative and visionary presence of a mother is a bond that Williams not only shares with Leon, who says, “Everything that I know I can trace back to my mother, my grandmother, and August Wilson,” but also with Wilson himself.

As I dove deeper into the biography and work of Williams, I noticed several similarities between the dramaturgy of Wilson and Williams. Both writers were well-read poets, whose plays at times contain language full of melodious metaphors. Plot was secondary to both writers; characters are the driving force behind their plays. Characters spoke to Wilson, and Williams once said that “if you’re in search of a play, you’ll never find it”; all one has to do is listen. Both Wilson and Williams, born one year apart, traveled away from their homes, and in doing so, eventually wrote a body of work that showcased the beauty of the rivers and the people that nourished them. Though Williams was interested in and did explore stories beyond Black experiences (such as “Eve of the Trial” in Orchards), the works produced by these men were testaments to the validity and worthiness of Black humanity. Like Wilson, who wrote for an audience of one, Williams didn’t write to make statements. He wrote about what mattered to him: goodness, God, land, redemption, self-authenticity, and hope. While Williams’s body of work includes historical figures (Denmark Vessey, Charlotte Forten, John Henry, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson), he was as concerned as his contemporary with illuminating the responses, plights, and causes of the unsung heroes and heroines impacted by history.

Williams once said, “All Black characters don’t have to be heroes.” While this is true, I think many would agree that, without even trying to be, he was a hero to many, especially to the people of his hometown in Burgaw. Williams earned many notable distinctions for his achievements in theatre, television, and film. But when his home state recognized him with a Governor’s Award and inducted him into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame, those two awards, given his sentiments about home, were undoubtedly close, if not the closest to his heart.

Fare you well, Samm-Art Williams. As you wrote in Home, I hope you are traveling along the banks of the White Stocking River so you can oversee the Saturday night fish fry. And may we, like you, reap the joy and abundance that comes from remembering the rivers that birthed us.

Omiyẹmi (Artisia) Green

Professor of Theatre & Africana Studies

William & Mary

The world recently lost the multi-hyphenate actor, playwright, director, and producer Samm-Art Williams just as his poetic, acclaimed play Home is receiving its first Broadway revival courtesy of the Roundabout Theatre Company. Willliams began his New York career as a member of the Negro Ensemble Company (NEC) and was an integral part of that company’s rise to national prominence in the 1970s. As an actor at NEC, Williams appeared in several key productions, including Steve Carter’s plays Eden and Nevis Mountain Dew, Charles Fuller’s Brownsville Raid, and Leslie Lee’s The First Breeze of Summer, which opened on Broadway in 1975. At NEC, Williams’ shared the stage with many NEC stalwarts and future luminaries: Adolph Caesar, Charles Brown, Barbara Montgomery, Arthur French, Ethel Ayler, NEC co-founder Douglas Turner Ward, and a teenaged Laurence Fishburne, to name a few.

Williams may be best known for Home, was first presented by the NEC Off-Broadway at the St. Mark’s Playhouse in 1979. The play transferred to Broadway in 1980 and later toured nationally and internationally. In the decades that followed, Home has received numerous regional productions. The same year that Home debuted on Broadway, Williams participated in one of American Theatre Wing’s “Working in the Theater” panel discussions, during which he revealed that “Home” was his 10th play.

Indeed, Williams was a prodigious dramatist whose output includes dozens of works, among them Welcome to Black River, The Sixteenth Round, Friends, Eyes of the American, Brass Birds Don’t Sing, and The Waiting Room. The plays of Samm-Art Williams are woefully under-examined and underappreciated. Aside from Home, only two of Williams’s full-length works have been published (Eyes of the American and Woman From the Town). A cache of his plays are scattered across different research library archives. A trove of Williams’s works written in the 1970s and ’80s are in manuscript form in the Negro Ensemble Company records, an archival collection at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Woodie King Jr.’s New Federal Theater (NFT) records archival collection, also held at the Schomburg Center, contains a manuscript copy of one of Williams’s last plays, the comedy The Dance on Widow’s Row, produced by NFT for its 1999-2000 season. Other plays of Williams are contained in the Douglas Turner Ward papers collection at Emory University Libraries.

Williams is one of the writers that the Black theatre collective Classix, of which I’m a member, believes has long been excluded from the American theatre canon. Williams, along with many other unheralded and unsung Black dramatists, rightfully deserves a place in it. The work of Classix s to raise awareness about these artists, whose plays have been neglected, by celebrating their legacies and shining a light on where different generations can gain access to their extraordinary work. Founded in 2017 by Awoye Timpo, the mission of Classix is to explode the classical canon through an exploration of Black performance history and dramatic works by Black writers. Our definition of a classic is a play that speaks profoundly to the times it was written and resonates with our own. One of Classix’s initiatives is a freely accessible catalog with information about Black playwrights. Each entry includes a short biography of the playwright, play titles and synopsis, production details and resources on how to find the plays at public and research libraries and archives. Williams is featured in the catalog. New entries are being added this summer and when complete this iteration of the catalog will contain over 50 playwrights.

Our goal at Classix is to bring plays by Williams and other overlooked Black playwrights back into circulation on the theatre conservatory level, embed them into the curriculum in theatre courses taught in higher education, and for these plays to be produced by professional theatre companies. Classix and organizations like the New York City-based Project1Voice and New Federal Theatre have been doing the necessary memory and cultural work by paying homage to these artists and advocating for their plays to be programmed in theatre seasons.

Theatres and conservatories must move beyond the model in which they are only staging the 10 most-produced plays of recent seasons and instead excavate the Black theatre archive for works that are vital, urgent, relevant, and timeless. Similar projects to amplify plays from the Black theatre canon have also sprung up in the United Kingdom with the Black Plays Archive and Staging the Archive, which is currently in development. It is imperative that works by Williams, as well as by his NEC peers—Judi Ann Mason, Joseph A. Walker, Gus Edwards, Lonnie Elder III, Paul Carter Harrison, Douglas Turner Ward, Leslie Lee, Steve Carter, Derek Walcott, Charles Fuller, and countless other Black dramatists of the 20th century—are studied and revived so that audiences can truly experience the expansiveness, richness and complexity of American theatre.

Through his stories, Samm-Art Williams wrote about the resilience of marginalized people like Cephus Miles in Home, Jesse Taft in The Sixteenth Round, or Polish Holocaust survivor sisters Anna and Janet in Brass Birds Don’t Sing. Williams was described by former Amsterdam News critic Lionel Mitchell as a “powerful writer behind all that brawn, a sensitive man outraged by corruption, a serious philosopher tussling with truth and reality—a wounded innocent capable of getting mad about our complacency, our indifference to corruption, our cynical attitude.”

During this bittersweet moment, in which new audiences will be discovering Home for the first time or revisiting the play, I thank Samm-Art Williams for his artistry and exploring the Black American and American experience through his storytelling on the stage and the screen. We give you a standing ovation, as you have now joined the ancestral realm and have been at last called home!

A.J. Muhammad

Samm-Art. Just saying your name makes me smile. Huge talent. Huge personality. And at 6’6”, huge guy! Thanks for giving me the chance to live in your words onstage. Kind. Funny. Brilliant. Never take off those jogging sneakers…! I love you, Big Guy!

Seret Scott

He was one of the nicest, most gentle, most interesting people I have ever met. I had the honor of working with him in the play Black Body Blues by Gus Edwards at the Negro Ensemble Company, directed by Douglas Turner Ward.

Samm had a fantastic sense of humor and was very aware of current circumstances of the time. I was able to take part in the repartee backstage before and after. He had a fantastic sense of humor and the swift comeback of a genius.That’s what he was! He was one the smartest people I’ve ever met.

I am at a disadvantage, because that was the limit of my association with Samm backstage at the Negro Ensemble Company. I of course knew about his endeavors writing for television. And did hear that he had gone to North Carolina to teach. His students are the most informed students; because of him they know their art. I never had the opportunity to sit down and talk one-on-one with him—that is my loss! Condolences from my family to his.

Norman Bush

Original Negro Ensemble Company member, 1967

When someone passes, we become more aware of our own mortality: how quickly time passes and how short life really is. The countless lives they’ve touched is the proof that they lived, loved, and were here. We find comfort in knowing that the brilliance and creativity of those earthly voices that have now been silenced can still be heard in the unforgettable body of work they left behind.

In honor of the legacy and passing of our beloved Samm-Art Williams, I asked creatives from around the country to share their remembrances. Samm-Art is truly deserving of every accolade we can send his way and more. This is mine:

On May 13, 2024, the industry lost one of its most revered and influential writers, actors, and producers of the latter half of the 20th century, Samm-Art Williams. He was 78 years old.

Samm-Art Williams has been called a titan of the entertainment industry, a cultural anthropologist, and a polymath. But my personal favorite is gentle giant. He is among our ancestors’ wildest and most prolific dreams.

Although I am fully aware of his impressive work as a playwright, screenwriter, and actor, I am in awe of his legacy on network television shows like Hangin’ With Mr. Cooper Martin, and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. Samm-Art’s powerful pen and brilliant producing skills helped make each show must-see TV for at least five seasons. He also wrote episodes for other notable shows like Cagney & Lacey, Miami Vice, The New Mike Hammer, the short-lived Good News, and the acclaimed, ahead-of-its-time dramedy Frank’s Place, which earned Samm-Art one of his two Emmy nominations.

The African proverb “Until the lion learns how to write, every story will glorify the hunter” best describes the literary genius and impressive curriculum vitae of Mr. Samm-Art Williams.

He is more than Black excellence.

He is Black greatness!

Erich McMillan-McCall

Founder/CEO Project1VOICE