Roger Q. Mason is at last receiving wide recognition, and it’s about time.

An award-winning Black and Filipinx playwright, Mason is in the midst of three major productions across the American theatre landscape: the world premiere of The Pride of Lions at San Francisco’s Theatre Rhinoceros, which ran earlier this month; the regional premiere of Lavender Men at Chicago’s About Face Theatre in May, and a regional premiere of The Duat at Philadelphia Theatre Company in June. Each play is a site-specific activation, reckoning and rippling with a rich, historically nuanced dialogue among the past, the present, and the future.

As a playwright, Mason’s work employs the lens of history like a kaleidoscope, challenging cultural biases that divide rather than unite us. When asked in a Zoom interview how they met these histories and turned them into story, Mason set the stage with reflection and sermon.

“It wasn’t always popular for me to be writing in a historicist way, especially not a revisionist historicist way,” they began. “I would often get criticized or encouraged to write about contemporary work, or questioned about the viability of these historically based stories when I was first starting out.”

As Mason shared their reflections, their strong, magnetic presence could be felt through the screen. Their voice rivals the warmth of a hearth. With each pause, beat, and breath, Roger speaks as a storyteller, drawing us in with intentional poise.

To Mason, history is “a survival guide in the present to build the future. It is the past telling us this is where we started.” And, of course, it’s also a source of drama. Outside of honing their craft and exploring their relationship to history at Middlebury and Northwestern, where they received their Master’s in English & Writing for Screen & Stage, Mason’s relationship to history as a creative source started at home.

“I was born in Santa Monica, Calif., and grew up in Koreatown, Los Angeles, but I really was born in a Texas household,” Mason said, describing their upbringing as “a time warp, because my grandmother and two aunts who lived with us in our compound were born between 1892 and 1910 in Del Valle, Texas, outside of Austin.” In this insular space were preserved narratives and cultural impulses from the Reconstruction era, Jim Crow, and the Great Migration, all passed down by the matriarchs who lived to tell the tale.

“I would say that my playwriting began at my grandmother’s yellow formica table,” Mason said. A wash of nostalgia and pride came over them as they recalled hearing her story about meeting Langston Hughes on his first tour of the South, when she was a member of the Gilpin Players; Mason’s grandmother remembered that Hughes complimented her on a scene she performed for him. “These are the types of tales that formed my sense of family and also history and memory,” they confirmed. But when they didn’t at first get into grad school “on the strength of those applications and the plays that supported them,” Mason said, they were “made to feel that the impulse to preserve history was not worthy of the academy and of the business that it was preparing people to enter.”

Undiscouraged, Mason stood firm in their journey as a playwright, holding true to their impulse to write history, as “these were the tools by which we survived in our present plight…You have an obligation to write down your version of how you survive so that the next generation has the same opportunity to survive that we left you.”

Mason describes The Pride of Lions as “a call to arms for us to speak the names of and celebrate the resplendence of trans, gender non-conforming, and gender-expansive people.” It follows five female impersonators imprisoned for indecency after they perform in a 1928 production of Mae West’s The Pleasure Man. Its world premiere in San Francisco meant that Mason and their work found their place in a city with a long and unapologetic history of progressing LGBTQIA+ rights and visibility, and joined its tradition of political resilience.

Lavender Men is a historical fantasia following Taffeta, a queer, fat, multiracial femme with the ability to conjure dead historical figures, including Abraham Lincoln and his young clerk Elmer Ellsworth. Taffeta and company take us through a journey confronting issues of visibility, race, and queer inclusion, as they speak to queer and trans audiences of color who have been erased and ignored for unapologetically being themselves. The About Face staging of Lavender Men is another kind of homecoming, as Roger noted: Chicago isn’t just the place in which they conceived the play and grew into their identity as a queer playwright; it’s also a city strongly associated with Lincoln, a longtime Illinois resident.

The final play in this dynamic trio, The Duat, is a solo performance portraying Cornelius Johnson, an FBI counterintelligence officer, as he fights for his soul in the Egyptian afterlife after a career of informing on Civil Rights activists in the 1960s. Though set chiefly in L.A., the play’s staging in Philadelphia links it to a city with a strong Black history, as it is home to more than 48 African American cultural and heritage sites dating as far back as 1639.

Mason’s use of historical fantasia to challenge narratives that have distanced us from absolute truth arrives at an apt time. All three of these plays roll out in an election year marked by waves of anti-LGBTQIA+ violence, censorship, and repression, as well as the continuing racial reckoning that has continued to rise since 2020. Using theatre as a seeing place, Mason said they define truth as a kind of mythology that we tell ourselves, “an ordering of facts that helps us comprehend and digest the intangible so that we can move forth with some empirical evidence of stability in an otherwise unpredictable world.”

This vision of truth is exactly what draws theatres and collaborators to their work. Mason’s writing is embodied and rhythmic, with a call for active reimagination. Lucky Stiff, who’s directing Lavender Men, said that Mason’s “kind of fantasia allows us to imagine a past that could lead to a parallel future in this world, the one we have to live in, where sometimes trying to make change feels like trying to shove a marshmallow through a keyhole—if failing to do that came with the possibility of disaster or death. It’s an intoxicating possibility.” While Lavender Men’s action plays out “in a cabaret of self,” Stiff said, this is no mere entertainment. Taffeta, they said, “claims her place in the historical narrative as a matter of survival.”

Building on the notion of revisionist history and fantasia, Mason has a keen intuition for the biases we hold. Mason, also a student of Luis Alfaro, writes with the inherited belief in civic patience, which challenges audiences to question, heal, or process what they have witnessed. Civic patience is also a practice for the playwright themself: a form of exercise in waiting for people to catch up. Looking back on this exercise, Mason said, “I proceeded trepidatiously into a career that I knew would not always be popular but was necessary because it moved the people and it gave them the civic medicine that they may have not known that they needed.” As their work premieres across the country, Mason has now reached a space where they no longer have to define and defend themselves as they did before. Instead, this period is an invitation to relax, soften, and collaborate.

Dramaturg Gaven Trinidad brought witness about working with Mason on another play, Waiting for a Wake, commissioned by Leviathan Lab. Said Trinidad, “I had the dear honor of being in the room in which they just take the words out of thin air. It’s just like jazz: beautifully structured chaos. And we thrive in that whirlwind of theatre movement. What excites me about Roger’s work is that they have such great care, and they acknowledge the good, difficult conversations we need to have within the theatre.”

While Mason and Trinidad were in contact as early as 2020, they first collaborated in person in February 2022. In an Airbnb in Crown Heights, the artists engaged in late-night exchanges of ideas and improvisation, music, singing, and channeling the plays through other mediums. Throughout their collaboration together on Waiting for a Wake, Mason and Trinidad explored the story’s impact on their bodies through discussion, reflections on lived experience, and rewrites sparked by questions and new creative impulses that emerged out of this somatic dramaturgy.

Reading Waiting for a Wake, I can testify that Mason’s imagery is evocative: a framed dollar bill passed down through generations, family dynamics that rival a house fire, and words that summon char and smoldering ember.

“I feel like it’s a long time coming for them, and they have such incredible talent, and I could listen to Roger talk for ages too,” said Taibi Magar, director of The Duat and co-artistic director of Philadelphia Theatre Company. Magar—who directed an excerpted version of The Duat in the 2021 Fire This Time Festival—is excited for the June production. Magar said she was drawn to The Duat by its inclusion of a live drummer, dance, and movement, and its invitation for Black discourse surrounding Civil Rights, equity, and justice. Magar said she saw parallels between the histories of Black Panther figure Elaine Brown and the character of Cornelius Johnson, and the intersections they faced that ultimately led to their destruction by the FBI.

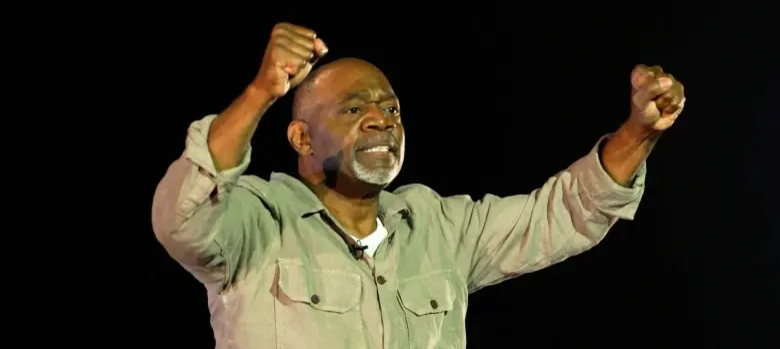

Gregg Daniel in “The Duat,” captured at the Kirk Douglas Theatre and presented as part of the third episode of Not a Moment, But a Movement. (Image courtesy of Center Theatre Group)

After spending some time workshopping the play with Mason back in December, Magar is especially excited to introduce it to her audiences. “Philadelphia has an incredible Black audience—just a riveting, diverse, thrilling audience, which we’ve gotten to experience already with our programming. I’m just thrilled to continue that conversation.” Magar shared that many plans are underway for the June production, including Black Out Nights, work with community partners, and a Juneteenth performance.

Trinidad, who is also the dramaturg for The Duat, also said of the play that it “shows the complexities around talking about race in the United States beyond our current vocabulary, and offers paths to healing through grace.” Through Cornelius’s journey, audiences get a look at the various ways Black people of the time viewed the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, as well as witnessing the colorism and violence within the Black community. Alongside that reckoning, though, is a message of hope and transformation.

At the center of all three plays, Roger Q. Mason is forging theatre that is resonant and which touches the psyche through rich language, intent, and inquiry.

“Whenever I sit down to write a play. I know that I am connecting with spirit,” said Mason. “And I am relaying that to whoever is open-minded and brave, is excited enough to hear the tale that I am giving them.” They hope to offer, they said, “a little taste of the sublime for them to do with it…whatever is necessary for their spiritual and social and cultural growth.”

afrikah selah (they/them) is a Boston-based multihyphenate cultural worker specializing in producorial dramaturgy, new-play development, and arts journalism.