Theatre director and educator Bill Bushnell died on Jan. 31. He was 86.

A feisty visionary who could charm his way into or out of any situation—except one—Bill Bushnell got his backstage pass to the universe on the last day of January 2024. Bush, as he was known, had been the artistic producing director of the Los Angeles Theatre Center, a six-year experiment in creating a multicultural theatre that focused on new work and generated a volume of production that seems impossible in today’s much more constrained environment.

LATC burned brightly but briefly. It was a large-scale start-up that ultimately went bankrupt, a singular event in the 20th-century nonprofit theatre movement, one that I think too few people know about. Operating from 1985 to 1991 in a renovated 1916 bank building that had purpose-built theatres, shops, offices, and rehearsal rooms added to it to create an 80,000-square-foot theatre factory, LATC at its peak had more than 25,000 subscribers attending as many as 18 full productions a year, plus a new-play festival, poetry readings, dance performances, a quarterly journal, and labs focused on developing new work, primarily from non-white and marginalized communities.

In my early 20s I was Bushnell’s executive assistant. This was during the middle period of LATC, after the chaotic and thrilling beginning and before the terrible end. I consider what I learned during those two and a half years to be the equivalent of a combined MBA and MFA, with exposure to extraordinary artists, technicians, thinkers, craftspeople, and management wizards, many who remain dear friends to this day. We forged bonds under intense pressure, fighting to accomplish the impossible, surviving a hundred varieties of institutional dysfunction and human frailty. Oh my, we had fun.

No one fought harder to make LATC a “going concern” as an educational, cultural, and social force than Bushnell himself. I watched him work six and often seven 14-hour days a week, giving notes to playwrights and directors following a preview performance, then poring over accounting printouts to decide which vendors to pay. The art-making was more audacious than the deal-making, but it was this hellish cash flow, and a debt-based capital financing package that had originally been hailed for its innovation, that ultimately ended the enterprise.

While the outside of the building still has the original vintage 1980s logo, LATC is now home to the Latino Theater Company, led by the people who powered LATC’s Latino Theatre Lab, José Luis Valenzuela and Evelina Fernandez. “We only exist because of him,” Valenzuela told me without hesitation. “Bush was a visionary who believed in diversity in the 1980s; it was where he thought the country was going. The art was revolutionary. He wanted to show the possibilities of the American theatre. And he gave so many opportunities to eager young people, creators who were hungry to speak with their own voices.”

LATC was not Bushnell’s first theatrical adventure, given his time at the beginnings of both Baltimore Center Stage and American Conservatory Theatre, and he directed several films as well. It was while he was filming On the Nickel, about 5th Street, downtown L.A.’s home to the homeless, that the idea for a theatre complex at 5th and Spring took shape. It met the ambitions of Mayor Tom Bradley and the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency to be the anchor for revitalizing the east side of downtown L.A. But the rest of the anticipated revitalization was glacial in its pace, and fancy Westside patrons didn’t renew their subscriptions after venturing downtown only to step over homeless people. Staff who finished work after dark were required to have a security escort to our cars in the lot across Main Street; I was grateful for the armed guard the night I found someone chopping up crack cocaine on the hood of my car.

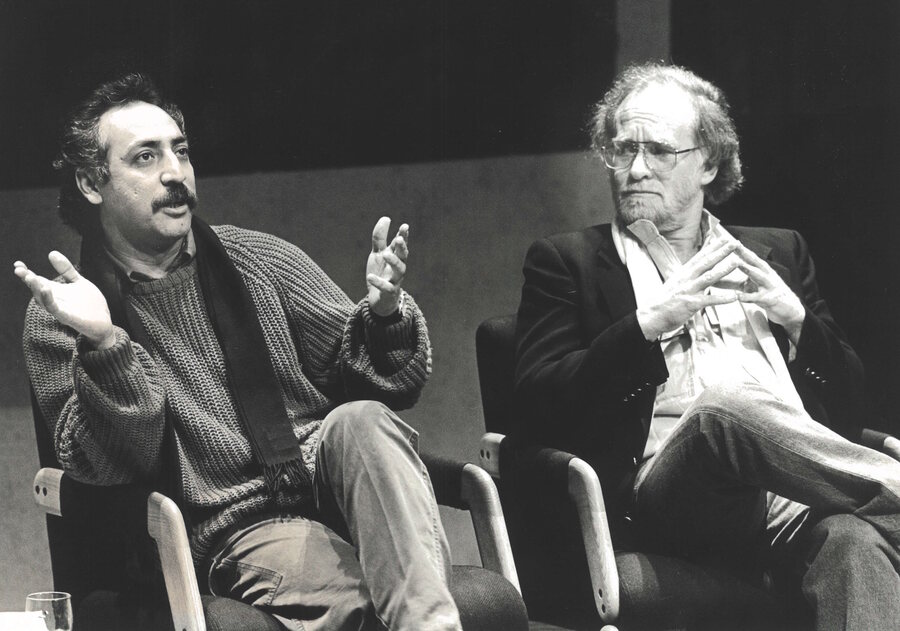

There are stories of LATC that have lived longer than the organization could, and while to today’s ears they sound, at the very least, inappropriate, they were symbolic of the energy inside the theatre. This was a time in the theatre world when yelling and throwing things was not unusual. The standout story has to be the one about Bush and Charles Marowitz tumbling down the vomitorium of the Tom Bradley Theatre (the complex’s largest, at 503 seats) in a fistfight over the volume of the gunshot at the end of Marowitz’s production of The Seagull. As Bush himself retold the story at the 25th anniversary gathering of LATC “alumni,” the fight was precipitated by Marowitz telling Bushnell he was “a phrase that began with a p and ended with whipped” for agreeing with LATC’s producer, Diane White, instead of Marowitz as director.

Bushnell’s relationship with White was essential to the story of LATC, since the two of them had met, and become romantic as well as artistic partners, at the predecessor to LATC, the Los Angeles Actors Theatre. Diane, who died in 2020, had a keen eye for talent—she became a fervent supporter of Reza Abdoh after LATC’s consulting director, Alan Mandell, brought Abdoh to LATC. There he made three original productions—Minamata, The Hip Hop Waltz of Eurydice, and Bogeyman—that were wild experiences of auteur-driven performance.

Working side by side until very near the end of LATC, long after they had stopped being a couple, Bush and Diane challenged one another and everyone who came into their orbit to be more original, more fierce, and to support more artists in the realization of their wildest imaginings. They fought each other viciously, and often publicly, yet each completed the other somehow, enabling LATC to reach beyond its grasp over and over again.

In many ways, Bushnell was far ahead of his time. For one thing, he was 20 years too early to see the revival of Downtown L.A. that has now begun, though it is still not complete 40 years later. Similarly, he recognized that demographics of LATC’s artistry needed to reflect Los Angeles, long before demographics were the driving force they have been for the last 20 years. Works by Culture Clash, Latins Anonymous, Eduardo Machado, José Rivera, Luis Valdez, August Wilson, David Henry Hwang, Philip Kan Gotanda, Josefina López, and more were central to the programming. Bush, and all the rest of us, created a ferociously creative space where ideas about how we might live as a society were both imagined and enacted. Contrast that with where we are now: The demographic changes that LATC modeled are now lightning rods in a new round of culture wars.

He was a strong supporter of women writers, as well: Anna Deavere Smith, Marlane Meyer, Constance Foreman, Jo Carson, Paula Vogel, Milcha Sanchez-Scott, Darrah Cloud, and others. He put women in charge of new-play development for most of LATC’s existence, including Morgan Jenness, Roberta Levitow, and Mame Hunt. And yet he was a classic patriarch, and quite a ladies’ man. Fitting for a man who had the Whitman quote framed in his office: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself. I am vast. I contain multitudes.”

He relished the acting pool of Los Angeles for its depth of talent and ability to sell tickets; I often heard him say, “We don’t discriminate against movie stars, we’ll pay them $425 a week like everyone else.” Pay them that $425 we did: Philip Baker Hall, Bill Pullman, Carole Kane, Tom Waits, Amy Madigan, Buck Henry, Bud Cort, Anthony Geary, Helen Slater, and many, many more. He and Diane maintained strong relationships with directors whose aesthetic was courageous and challenging, most notably David Schweizer, who directed one of the productions that opened LATC and others along the way, and was brought in by the board to lead the theatre as its collapse became inevitable.

In the end, all the creative fervor and national awards and high-powered board, and the heroic efforts of the staff, could not keep the theatre afloat. The bonds came due, and that was the one thing Bushnell couldn’t charm his way out of. A last-ditch deal with the City of Los Angeles to take over ownership of the building—without responsibility for facility costs—was truly the end of the road. A few staff members remained to operate the building and rent its world-class facilities to a variety of L.A. companies, until the city created a process to award it to the Latino Theater Company and the new LATC began.

After LATC offered life-changing opportunities to so many of us, myself at the top of that list, Bushnell reinvented himself a few more times. He worked for a time at Cal State Long Beach, then left Los Angeles with a sailboat in sight. I know he interviewed for other leadership positions in the theatre world, but I believe he was marked “untouchable” by LATC’s demise, and by the many bridges he had burned throughout his career. He met Leita Hulmes while working for FEMA, doing public relations following disasters, and they retired together to Cuenca, Ecuador. She was by his side when he breathed his last, in a sudden collapse that left no time for long goodbyes. He died, as he lived, on his own terms.

This article was greatly improved by the editorial advice of LATC’s former co-literary managers, Stephen Weeks and Peter Sagal, and by the former prop master, Cat Dragon, who serves as the company’s unofficial historian.

As the director of Artistic Logistics, Lisa Mount works as a consultant with arts organizations focusing on strategic thinking, organizational advancement, and equitable practices. Current and recent clients include the Exploratorium, Cleveland Public Theatre, the New Harmony Project, Mixed Blood Theatre, Dance/USA, the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies, the Goodman Theatre, and the Fountain Theatre. She produced the acclaimed Headwaters community story plays at the Sautee Nacoochee Cultural Center, and continues to create and perform there. She has served on the board of Alternate ROOTS since 1991.