We were in tech, and Moisés Kaufman was asking lighting designers Alejandro Fajardo and Ben Stanton for an adjustment. A stream of light was supposed to be seeping through a window in Caracas, Venezuela, and Kaufman wanted it to look just right.

“The light in Caracas in the morning is very beautiful,” Kaufman explained.

Getting the light right was important. It’s a light many of the cast members of Las Aventuras de Juan Planchard know well. And because the play was premiering last fall at Miami New Drama, a company Kaufman co-founded with another Venezuelan American, Michel Hausmann, the audience was likely to know that light well too. More than seven million Venezuelans have fled their country as a result of Hugo Chávez and Nicolás Maduro’s regimes, and the largest concentration of this exodus in the United States, according to the Pew Research Center, is in Florida.

The light Kaufman was tweaking to fit his memory is a sight some cast members in Juan Planchard may never see again. Many of the actors, among them some of the most celebrated performers the nation of Venezuela has produced, have been effectively exiled from their homeland, and the reason for that exile was at the very center of the drama. For Las Aventuras de Juan Planchard—and the process of its making, which included years of prior development with Kaufman’s company Tectonic Theater Project—offers a lesson in how to lose a country, one we can all learn from. “The country that I knew,” said Kaufman, “perished.”

Set in 2011, the play is based on Jonathan Jakubowicz’s novel of the same title, which follows the exploits of its titular antihero, a young operative in the employ of Venezuelan general-turned-dictator Hugo Chávez. Juan accumulates wealth and power through a series of corrupt dealings in direct contradiction to the government’s purported socialist ideals. Jakubowicz’s book became both an emblem and tool of resistance upon its clandestine publication in November 2016, and rose to popularity just as protests against the regime of Chávez’s successor, Maduro, were coming to a head. Jakubowicz recalled that resistance groups used an app called Zello to organize against the government, share his book, and even read Juan Planchard aloud.

“The readings were often interrupted by crucial information about specific groups approaching the protesters,” Jakubowicz said. “It was a way to keep everyone connected and alert, by listening to a book that spoke to them. At some point there were 50,000 people simultaneously listening to the book being read. It was obviously very humbling and special.”

The story follows Juan, whose devotion to the strongman leader is a payday for him, as Chávez systematically follows the playbook of his hero and mentor, Fidel Castro, little by little dismantling his country’s democratic institutions and constitution. Juan is part of a generation of young Chavistas who got filthy rich off the regime’s self-dealing corruption while most of his country starved.

“My name is Juan Planchard, I’m 29 years old, and I have 29 million dollars in my bank account,” is how the play starts. Juan goes on to list his possessions: a private plane, properties around the world, including in New York City and Madrid. Soon he meets an American woman in Las Vegas, a high-end sex worker, though Juan doesn’t know that. This miscalculation, as well as his assorted thefts and moral compromises, lead to a demise of Shakespearean proportions. Kaufman said he sees Juan as a kind of Richard III, addressing the audience in the “winter of his discontent.”

Moral responsibility infuses the piece, starting with its inception. “To me,” said Kaufman of his drive to create the play, “it felt like a moral debt.” Kaufman was born in Venezuela and arrived in the U.S. in 1987 to study and work in the theatre. When Kaufman left home, Venezuela was still among the “oldest and sturdiest democracies in Latin America. Then, in 1999, Chávez came to power. Under the rhetoric of social justice and equality, there was a dictator ready to pounce. Most people that were in the U.S. were terrified,” he said of his fellow Venezuelans.

As years went by, things incrementally got worse. By 2017, the year Kaufman’s father died and the last time he was able to travel to Venezuela, the country was aflame with protests, which were in turn crushed by Maduro’s authoritarian regime. According to Human Rights Watch, the government killed more than 19,000 civilians between 2016 and 2019, largely in acts of democide and extra-judicial murder. Kaufman has not returned since, as he fears the consequences of having been too vocal against the Chávez and Maduro regimes. Many of the show’s actors are in the same position.

All of this history is important context; it’s the reason rehearsals for this piece were so incredibly charged. Of the nine actors, five stated during rehearsals that they “can never return” to Venezuela for fear of death or imprisonment. The stakes of making theatre rise under conditions like this. One actor said he had a hard time memorizing lines for the first time in his life, because there was a “part of my body,” he said, “that doesn’t want to know these lines.”

Elba Escobar, who had a 50-year career in Venezuela as an actress, writer, and artist in TV, radio, and film, had to leave the country in 2014 after her son was kidnapped—twice. To play the role of Juan’s mother, Escobar said, “My process has been one of working through pain. Because it’s a huge responsibility to represent a Venezuelan mother.” As she spoke, her voice cracked like an open wound.

Orlando Urdaneta, who played Juan’s father, was a voice of the resistance in Venezuela at one point. Kaufman likened him to the country’s Johnny Carson. Urdaneta himself said he was a bit like Bill Maher, with a comedy news show which moved from funny to acerbic as the country increasingly fell under Chávez’s claw. His work and voice became extremely political, and the government was literally after his head. He decided to leave after one insider told him, “People like you end up killed or in prison, and it doesn’t look like you’re going to prison.”

Urdaneta told Kaufman that this would have been the moment in his life, after such hard work, when he would have had theatres and streets named after him. Instead, in his late 70s, he’s “matando tigres”—literally, killing tigers, which colloquially translates to hustling, doing anything you can to make ends meet, taking any gig you can to make it work.

“When you fight the way we did, you imagine three ends: victory, death, or prison,” Urdaneta said. “What you don’t imagine is this…” He trailed off for a moment, using his hands to point to the current predicament of exile all around him, and then added, “We are living a kind of hell.”

The actor who played Juan, the spectacularly good Christian McGaffney, was only just beginning to feel exile, due to a movie he recently starred in. Titled Simón, the film by Diego Vicentini tells the story of a young freedom fighter who takes the opposite route from Juan and is tortured as a result. The truths the film depicts are the reasons McGaffney cannot return to Venezuela.

“It’s not just the emotions you go through in rehearsal but the ones you take home,” said McGaffney. After the first tech rehearsal, he said he found himself at home feeling caught between the characters of Simón and Juan, sitting with the reality of his country, “which shouldn’t be like this,” and realizing he couldn’t return. He cried like a baby on his wife’s shoulder.

As you might imagine, with history like this sitting on their skin and living in their bones, the Kleenex box made its rounds from actor to actor throughout the rehearsal process.

This is where the work of Lauren DeLeon, the show’s intimacy coordinator, became unexpectedly important. DeLeon, who got her master’s at NYU during the pandemic, focused her studies on the theoretical decolonizing practice of her work, as she wasn’t sure “if people would ever kiss onstage again” after the pandemic. Theory became practice in this show, though in an unforeseen way. Though the show had some sexually explicit scenes, those weren’t her main focus. Instead, the core of what she did was to try to understand the blurry boundaries between the actors and the characters they were playing.

DeLeon’s job went into overdrive, she recalled, when Kaufman started receiving emails from the cast about the material becoming very heavy for them. It was at this point that DeLeon introduced a unique version of de-roling practice. De-roling is usually designed to allow actors to remove themselves from the work of the role and re-enter their own lives. “In this case, that’s impossible,” explained DeLeon. No matter what, these actors were going to take their work home with them, because the work was so closely intertwined with their own stories.

DeLeon knew she would have to adapt. The last thing she wanted to do was to insist that there was only one “Western” way of making theatre, or only one way to deal with the idea of intimacy, whether psychological or physical. What’s more, these were mostly Latiné actors who were coming at the very idea of intimacy from a different perspective. So instead of creating a moment in which the actors entered, then shed, their characters, DeLeon created what she called a “grounding practice,” which sought to empower the actors through their pain. She led the actors into a very simple tapping-in-and-out ritual that included getting into a circle, making eye contact, taking three breaths in unison together, then clapping at the top and end of each rehearsal.

These actors were, after all, making an active choice to tell a story close to themselves. Their art, according to both Kaufman and DeLeon, was an act of resistance, even revenge. Art is the place, Kaufman asserted, where the individual affects society. This can be particularly powerful when you are expressing the story of a people whose own freedom of expression has been destroyed.

“Since the early 2000s, there’s been a huge effort from the government to shut down freedom of expression, and that meant that TV stations were either shut down or lobotomized by the government,” said Miami New Drama artistic director Michel Hausmann. “The film industry, which was beginning to thrive, became hijacked by the government, so suddenly our ability as Venezuelans to tell our own stories got profoundly restricted.”

Though he’s helped tell many kinds of stories at Miami New Drama, the core freedom to tell any story, including that of his own muzzled people, is one reason Hausmann is now making theatre in the U.S., not Venezuela.

On opening night, the pent-up energy was palpable. In the audience that evening were Venezuelans and citizens of Miami, people who trace their roots back to Cuba, like myself, and to Nicaragua, and so many other places—people whose families have, as Escobar told me, “a wounded heart that joins them.”

Nowhere was that heart more pierced than in a scene near the middle of the play. Juan visits his parents to introduce them to his American girlfriend. The conversation goes like this:

Papa: You are dishonest, son. That’s not what I taught you.

Juan: The country is dishonest, Dad. I’ve only adapted to the rules of the game.

Papa: Listen to me. Get her pregnant and leave this place. This country is fucked.

Juan: Then you guys leave too!

Papa: Me? Never. This is my home. I was born in Caracas and I’ll die in Caracas.

At that moment, on the night I saw the show, the air left the room for a moment, and the silence stung. Many in that audience know what it’s like to have a diehard in the family—the one who will not give up, who won’t abandon the motherland—even as it is necessary and painful for the rest to leave. Many of us know what it means for umbilical cords to be cut by tyranny.

The pain reached across generations in that audience, and when the scene ended, I too felt a cord inside me snap. I cannot imagine what it must have been like for Urdaneta, as the father, to say those words onstage. He, who had to leave his country or else be murdered by the regime, and whose bodyguard, as he recounted to me, was assassinated. Or what it felt like for McGaffney, who cannot return to his country for fear of imprisonment, to deliver the next aside to the audience as Juan: “That’s my dad, Venezuelan to death. So Venezuelan that he believed more in the country than the country believed in him.”

There were moments, after having been privy to the rehearsals and the hearts of the actors onstage, that I longed for the things they told me to actually be onstage. Instead we were watching the adventures of the enemy. This is, of course, part of the art. One has to sit in the audience and come to terms with our unreliable narrator, Juan. Just as with Richard III, there are layers, and here one must unravel the satire and irony, expose the seams, to understand that there is more than what seems to be—to sift below surfaces to find truth.

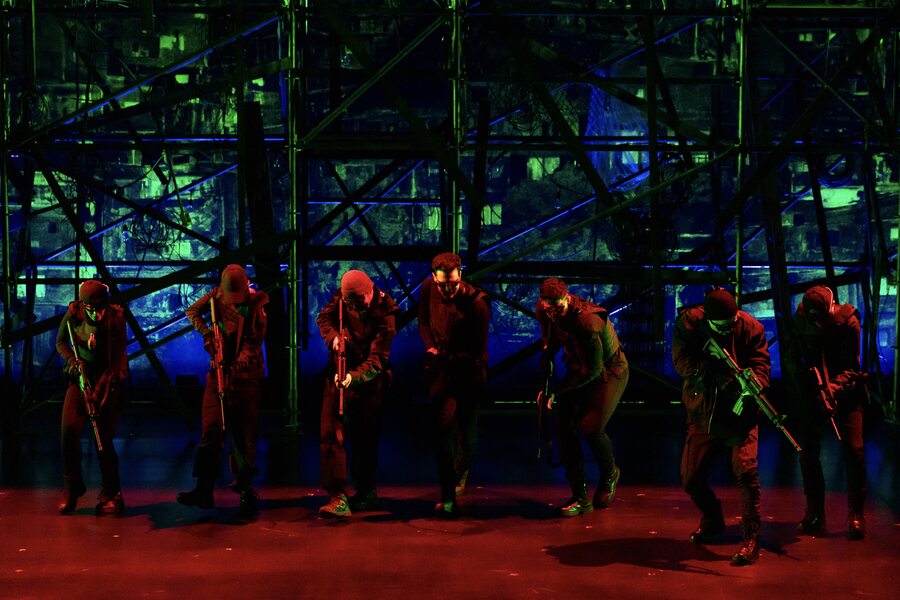

That surface was quite appealing, I might add, which made it difficult to parse the truth from the lies. This was part of the point. With a budget of roughly $1 million (including development), the production had a lot of gloss. Scenic designer Derek McLane put a beautiful high-end New York apartment at the center of the design, but also created within it the space to move locations from Vegas to Caracas, from a private jet to a place called “The Stench”—a horrifying place where the country’s dead lie piled up, one on top of the other, where gangs execute enemies and bodies decompose.

The danger of such a seductive surface, though, lies in the chance that more Anglicized audiences won’t understand the history, the context, and the layers of lies spewed by the enemy onstage, and may instead take some of it, even unconsciously, at face value. That’s a risk Kaufman will have to grapple with if the play has future productions. This is not to say that audiences are unintelligent, or can’t do their own research, but that when dealing with authoritarianism, the truth can be hard to find, as authoritarians are very good at silencing opposition. When dealing with regimes like Chávez’s and Maduro’s, history has to be reconstructed out of the oral histories of those regimes’ silence—like those of the actors in this case.

All the more reason I longed for others to see and hear the stories of repression and exile I’d heard from the actors and Kaufman: the resistance of the rehearsal room.

That said, the very working out of all these complexities was part of the beauty of Las Aventuras de Juan Planchard. And to have a new bilingual piece, launched by a theatre that has been creating space for such pieces to take their place inside the American canon, is a big deal, and long overdue.

As long as there are stages upon which works like this can be staged and processed, we stand in a place very different than Juan, who believes there is no way out of The Stench. As long as there is a place to cast a true vote, a place to speak freely, a place to write and be heard, a place to tell your story, as Shakespeare himself wrote, “Truth will come to light; murder cannot be hid long; a man’s son may, but at the length truth will out.”

That is the work we do. The light, and making sure it looks just right as it shines on the truth—that’s what matters. That light, in the end, is everything.

Vanessa Garcia is an award-winning Cuban American playwright, screenwriter, novelist, and journalist/essayist. www.vanessagarcia.org. Instagram: @vanessgarciawriter