The 1491s stared at the classroom’s blank whiteboards. The Native American sketch comedy troupe had never written a play before, but here they were at Oregon Shakespeare Festival, on a co-commission from Rhiana Yazzie’s New Native Theatre, on the assumption that they had a show in them. It was 2018, and the 1491s were among the first Native artists commissioned through OSF’s American Revolutions program. They needed to come up with something.

“It was a big learning experience for us,” recalled Ryan Redcorn, one of the five members, along with Dallas Goldtooth, Sterlin Harjo, Migizi Pensoneau, and Bobby Wilson. “Nobody in the group has theatre experience. We’re all just YouTube clowns.”

Harjo, who had directed features and documentaries would go on to co-create the acclaimed TV series Reservation Dogs, said that film and TV were the group’s goal, not theatre. “We never thought about a play,” he says. “I never even thought it was possible.”

In fact, inside that classroom at OSF, they spent some time trying to shoot footage for a Kickstarter campaign for a feature film, which proved the most productive part of their work at that early stage. “We would just draw dicks on the dry erase board for half the day, then goof off and try to figure out what we were going to do,” Harjo said.

Soon enough, however, they turned serious—or at least as serious as a bunch of comedians could get. “We were very hungry and inspired, and it felt like this was our shot and we wanted people to hear what we had to say,” Harjo said, “so we started talking about what history we wanted to tell. Then we worked fast.”

Redcorn said that each member brought something different to the mix, creating a unique blend of drama, history, and humor that mixed subtle and absurdist with the low-brow and slapstick.

The result was Between Two Knees—and yes, Harjo confirmed, the title is both a dick joke and an important historical reference, as the play is set between the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890 and the American Indian Movement’s takeover of Wounded Knee in 1973. “That’s a great outline for a play about our history and American history, and it gave us parameters and challenges for the show,” he recalled.

After the premiere at OSF in 2019, the show was staged at Seattle Rep, the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, and Yale Rep in New Haven. Now it’s playing at New York City’s Perelman Performing Arts Center through Feb. 24. (It’s something of a homecoming for the show, as PAC NYC’s artistic director is Bill Rauch, who commissioned the play when he was artistic director at OSF.)

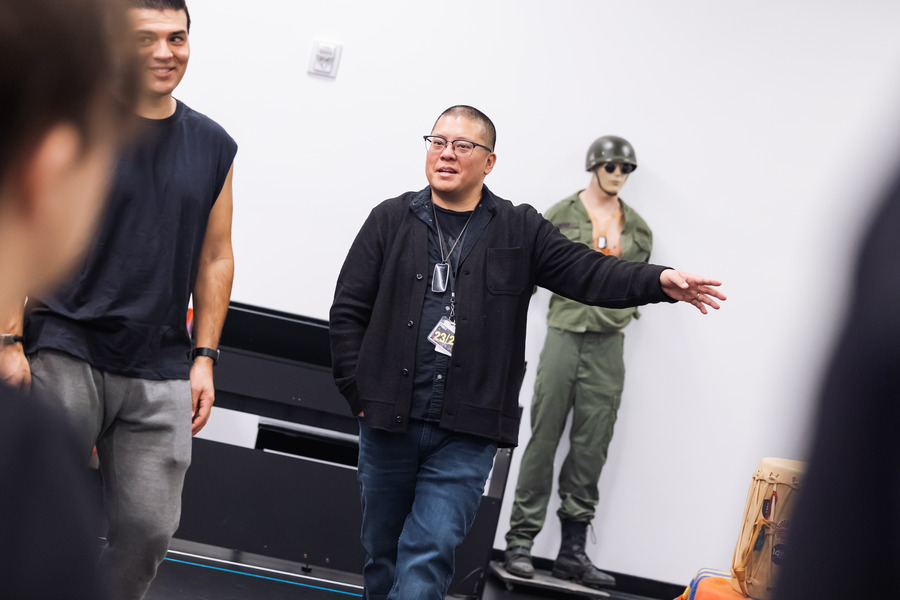

Eric Ting, who has directed all five productions, said that the group’s lack of playwriting experience ultimately proved advantageous.

“The guys write in a way that’s completely liberated from what we think of as traditional theatre,” he says. “And it’s a radically different idea of Native American theatre—no one had seen anything like this.”

Shyla Lefner, a cast member throughout, said that even the first readings, when “we just had a couple of scenes and a lot of bullet points,” were powerful and empowering. “It’s very rare that the Native voice gets to address these moments in our history head on, with humor and without pulling any punches or necessarily taking care of the audience.”

The play includes scenes exposing the Catholic Church’s mistreatment of Natives (which have reportedly sparked walkouts) and of Natives burning down the controversial boarding schools built to “Americanize” them. But there are also heartfelt family scenes and plenty of humor. After all, said cast member Wotko Long, “Humor is what got our people through the Trail of Tears. That’s how we survived.”

Redcorn said that OSF’s support for their work was patient and unending, no matter how strange or boundary-pushing the show became. “Usually, the hardest part for us is convincing people to allow us to do what we do,” he said. “Usually, we get, ‘No, no, don’t do that,’ or we have to explain things and deal with pushback; everybody in the group is highly anti-authoritarian. But OSF was really supportive.”

Ting agreed, adding that OSF could easily have gone with a trunk-show version on its second stage, but instead “broke records for the number of costume changes and wigs for an actor. OSF had a real desire to commit resources and give it what it deserved. This is a very big play that asks a lot of every theatre that produces it.”

Ting was brought on by Rauch back when the group had just 15 pages. The director’s mellow vibe and collaborative approach were crucial, not only because the troupe was new to theatre but also because someone had to pull together the work of what he called “five unique and distinct artistic voices bumping up against each other.”

While Ting is not Indigenous, he understood their work intrinsically, Redcorn said, and was able to deal with a group of men used to directing their own work. “We felt the content was safe with him,” he said. “He’s one of us now.”

(Ting said the group jokingly told him at the start, “There’s one of you and five of us, so we’ll always win.”)

Wilson and Redcorn were at OSF consistently during the show’s development, while the other three were more often away, for everything from Reservation Dogs (Harjo) to activism at Standing Rock (Goldtooth). Still, they remained tightly bound, writing and rewriting by consensus.

The cast, which has largely stuck together throughout the different productions, is a mix of veteran actors like Sheila Tousey—whose credits range from movies like 1992’s Thunderheart to plays like Manahatta, which she appeared in both at OSF and last year at the Public Theatre—and Long, a Muskoke song keeper, who had never done theatre before.

“He’s a cultural guide, inspiration, and friend,” said Harjo, who was initially reluctant to ask Long to audition in case he didn’t get the part or was overwhelmed by the demands. But he filmed multiple takes for Long to nail the audition, then watched as Long became “the heart of the play.”

“He leaves me crying every time,” Harjo said. “It’s one thing to enter these spaces and bring your stories to it, but it’s a whole other thing to bring your community to it.”

Ting confirmed that Long’s role goes beyond his performance. At the daily smudge circles preceding rehearsal he has shared stories about his father’s time in boarding schools where he and other children were whipped, and about being drafted and sent to Vietnam.

“History remembered is really important, and this play is a new way of educating people,” said Long, 72, adding that he views the cast like “my kids and grandkids.” He told them about coming back from the war and being told by the army that he and other Native soldiers couldn’t leave their posts when their unit was sent to Wounded Knee in 1973. “They were right—we would have gone and helped our people.”

Redcorn said that creating a Native comedy was meaningful because most plays, movies, and TV shows featuring Indigenous characters “don’t have our humor and don’t have Indigenous people winning or loving. Our show has love and laughter, where most stories of Indigenous people are just about death, mourning, and lamentation.”

The show’s humor has a sting, but also a generosity of spirit that, Ting said, invites audiences to laugh at themselves. He points to an early scene where the narrator, Larry, breaks the fourth wall and passes a can for donations through the audience (the money raised goes to a local Native organization serving Native youth). At one point he quips, “Don’t be cheap—when it’s all done, you’ll still own everything.”

Harjo and Redcorn emphasized that they write for Native audiences first and foremost, adding that Between Two Knees makes clear early on that it’s designed to laugh at both Natives and whites. “We’re not just there to make fun of white people,” Redcorn said.

Added Harjo, “We always stick to our guns and make something for Native audiences, but the trick has always been to welcome you in while still holding true to what we’re doing.”

Redcorn said they “abhor trying to explain things,” but that telling their own truths creates enough universality for most audiences to find a way in. If, on the other hand, Redcorn said, if they’d “written to a theatre audience, we would’ve sacrificed real estate that often gets sacrificed. That’s the part where the humanity of Indigenous characters gets fully fleshed out.”

That approach has paid off—Between Two Knees was OSF’s highest-grossing play of the year, and it has met with success everywhere it’s played, showing that Indigenous stories can be profitable. But even if critics and audiences had rejected it, the 1491s would have remained unbowed. “It has no bearing on how I will be buried and how I conduct myself here in my community,” Redcorn said. “We are beholden to our community first. If other people like it, great.”

Not everyone has loved it. Harjo said that at OSF the 1491s delighted in standing in the lobby to witness the walkouts. “One lady came out saying, ‘It’s just so offensive, but my husband is still in there—he likes it.’ I love how polarizing it was.”

Online audience reviews likewise had no middle ground. “People said it was the most amazing thing they’d ever seen or they were mad they couldn’t give it zero stars,” said Redcorn. “I got a lot of joy out of reading the hateful comments.”

Since that dick-covered chalkboard in 2018, the 1491s have become stronger writers (all did at least some work on Harjo’s Reservation Dogs) and Ting said they’d introduced subtle tweaks before each production that have improved the play. “They’re more thoughtful and can get to the heart of the matter more easily now,” he said.

Not only the script has changed since then, of course, as Ting noted “the collective trauma of the pandemic and the racial reckonings brought on by George Floyd’s murder.” Native voices are finally being heard in pop culture: on TV with Reservation Dogs, Rutherford Falls, and Dark Winds, and onstage with Mary Kathryn Nagle’s Manahatta and Larissa Fasthorse’s The Thanksgiving Play, which made it to Broadway.

“Between Two Knees was originally a harbinger for all this, but now it’s in conversation with everything that has happened,” Ting said.

Harjo hoped that these social and cultural changes mean audiences may be more open to less traditional theatre. Or, as he put it, “They may finally be ready and willing to see what the fuck we have to say.”

At the Perelman, the show returns to a three-quarter thrust stage, which is how it originated at OSF. “With the thrust, audiences see other audience members across the way, which either makes people really uncomfortable or, when they give themselves permission to be a part of this, really boisterous,” Lefner said.

Everyone agreed that the audience atmosphere is enhanced when Indigenous people are in the audience. While Ting noted that OSF and Seattle Rep are in regions with a greater Native presence and more exposure to Native culture, the Perelman, like earlier productions, will subsidize tickets for Native audiences.

“When there are Native audiences, you feel the energy,” Lefner said. “That gives everyone else in the audience permission to laugh, and then to have confused feelings after laughing.”

Harjo pointed to the finale, “So Long, White People” as the perfect example, with many audience members standing, swaying, and singing along.

“The song lets everyone in on the joke, no matter where you’re from,” he said. “They’re singing as if to say, ‘Can we correct course to fix some of the things that our ancestors did or people who came from Europe did?’”

Redcorn stressed that while the troupe doesn’t feel they need older white audience members’ validation, seeing people “who may be the furthest intellectually and emotionally from where we want them to be in how they vote in terms of laws that cause harm to Indigenous people” on their feet is “the best thing ever.”

Even better, he added, is to “watch Indigenous people in the crowd and the look on their faces as they watch those white people sing that song.”

An earlier version of this piece did not credit Rhiana Yazzie’s New Native Theatre as the co-commissioner, with OSF, of the original production.

Stuart Miller (he/him), a writer based in New York City, is a frequent contributor to this magazine.