Joan Holden, for many years the chief playwright of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, died on Jan. 19. She was 85.

It was an annual occasion I looked forward to during my quarter-century as a San Franciscan. On a summer day, I would head with friends to the grassy slopes of Delores Park, or to Washington Square Park in the heart of North Beach, to join a genial crowd gathered before a portable stage. A truck nearby was emblazoned “The San Francisco Mime Troupe.”

A jazzy combo would swing into an upbeat mini-overture. And then the play would kick in: always topical, always political, but wooing you with gags and songs and broadly engaging acting, whether the subject was Ronald Reagan’s presidency, U.S. military involvement in Vietnam or Central America, cultural amnesia or working-class angst. Whatever the subject, the production bristled with the witty dialogue, theatrical savvy, and political fervor of Joan Holden, the troupe’s chief playwright for much of its heyday.

The Mime Troupe has been an inspiring model for many other politically minded theatres and teatros in the U.S.. (It is also the first, and so far only, political theatre outfit to win a Regional Theatre Tony Award, in 1987.) And the company is still regaling audiences in Bay Area parks, under the leadership of a new generation of leaders, including manager Ellen Callas and playwright-in-residence Michael Gene Sullivan.

But for several decades, Holden was the chief writer and ingenious instigator of touring productions that boasted her signature blend of keen satire, au courant news flashes, power-to-the-people messaging and populist entertainment. In her time with the troupe she wrote or co-wrote more than 30 plays. She was, noted playwright Steve Most, the co-author with Holden and Jael Weisman of the Dell’Arte Players show The Loon’s Rage, a “great collaborator.”

When I met Joan in the early 1980s, I was a little intimidated. I was a young wannabe critic and a longtime Mime Troupe fan. She was so keenly intelligent, so feisty, so indefatigable. She didn’t mince words in an interview or in conversation, and had the rare gift of saying exactly what she meant. She was also disarmingly funny—and fiercely political.

The Mime Troupe was founded in 1959 as a “guerrilla theatre” by R.G. Davis, who melded his leftist principles and fascination with Italian commedia dell’arte into radical park shows that snagged international attention, particularly the controversial anti-racist play A Minstrel Show or Civil Rights in a Cracker Barrel. (By the way, “mime” for this troupe never meant silent.)

In the late 1960s, Joan happily joined the group. “Something clicked: the amount of energy on the stage, the fun that people seemed to be having,” she told San Francisco Chronicle theatre critic Lily Janiak in a final interview. But an artistic and political schism developed, and Davis moved on. The Mime Troupe became a theatrical collective that paid everyone the same wages, eschewed star billing, and crafted shows by sometimes hard-fought consensus.

Once Joan enlisted, the troupe quickly had national success with several sharply relevant Holden scripts. One was the feminist melodrama The Independent Female; another, The Dragon Lady’s Revenge, an exceedingly clever adaptation (and subversion) of misogynistic, Asia-demonizing Hollywood films, and an exposé of the CIA’s involvement in the Indo-Chinese drug trade. Dragon Lady traveled to New York and received the first of the company’s three Obie Awards.

The Mime Troupe continued as a collective. So much so that, when I observed a rehearsal at their funky Mission District warehouse headquarters, I was struck by how everyone—from the actors and musicians to the publicist and business manager—voiced their opinions and ideas about how the show should develop.

That was just fine with Joan. For all her militant anti-capitalism, and her energetic sparring with those who debated with her, I also came to know Joan as genuinely warm and inclusive, not a snob or lefty elitist. (She was also the loving mother of three daughters with her longtime partner and Mime Troupe cohort, Dan Chumley.)

Back when it was hopelessly uncool, Joan told me she subscribed to People magazine to keep her fingers on the pulse of mass “lowbrow” culture. She loved to appropriate genres and found inspiration for plays in comic books, classic movies, and popular TV shows, as well as news accounts and investigative reporting. She always took joint credit with her collaborators, just as such longtime Mime Troupe actors Sharon Lockwood, Joan Mankin, and others who fully animated Joan’s eclectic tales never got top billing.

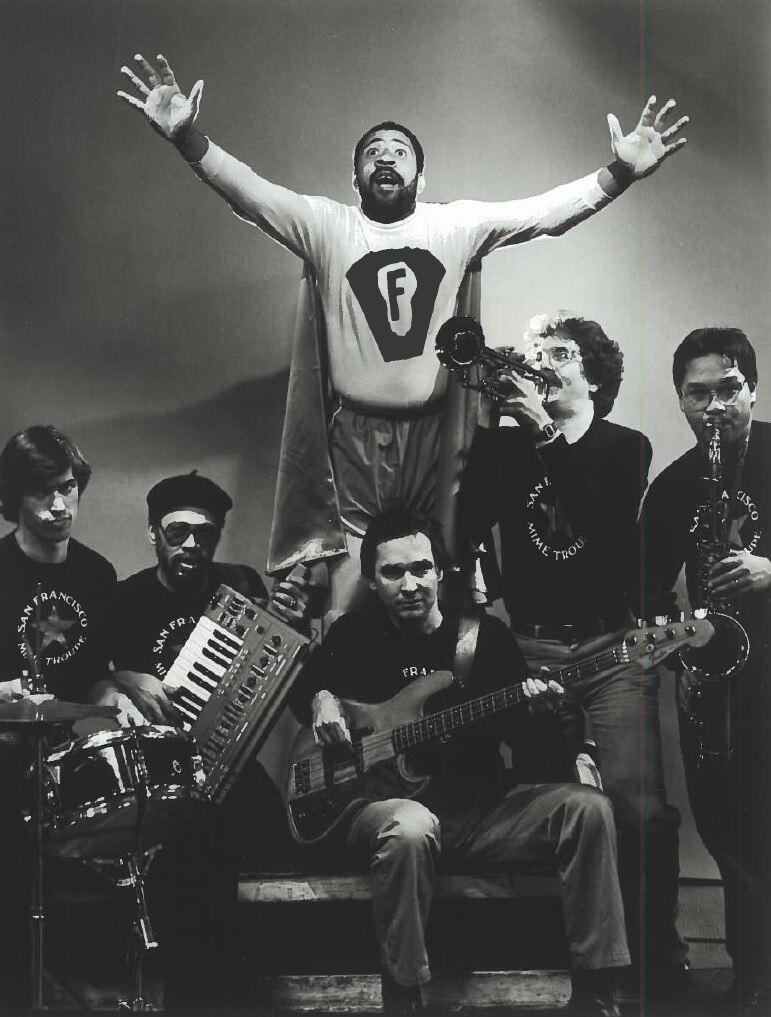

Many Holden-led plays turned commonplace people into superheroes. A favorite of mine was Factwino Meets the Moral Majority, which featured Barry “Shabaka” Henley as a homeless alcoholic who transforms into a Superman-like character. Instead of physically vanquishing adversaries, he pops up to correct the lies of right-wing politicians with proven facts. (Man, do we need him now!) The show was outrageous, hilarious, and right on target.

Another hit that was among her best was Ripped van Winkle, with a nod to the famous Washington Irving story, in which a ’60s-era San Francisco hippie takes an acid trip that magically zonks him out until the late ’80s. He wakes up to find himself hilariously at odds with a city and society steeped in greed and yuppie materialism—and there’s no more counter to that culture. He longs to “come down” off this bummer psychedelic time travel escapade, but there’s no turning back from the America he finds.

Joan retired from the Mime Troupe in 2000 but continued to write plays. A notable one was an adaptation of Barbara Ehrenreich’s best-selling book Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, a firsthand study of the lives of low-paid workers. It debuted in 2002 at Seattle’s Intiman Theatre and has since had numerous productions around the country. A more recent musical play, FSM, looked back to an era Holden knew well to explore the influential Free Speech Movement at University of California in Berkeley during the ’60s. Produced by the senior theatre company Stagebridge, with Daniel Savio (son of FSM leader Mario Savio) as co-composer, it premiered in 2014 at San Francisco’s Brava Theater Center.

No matter how dark her view of American mainstream politics and society, Joan’s plays always rallied against apathy and held out hope for more awareness and more activism toward a more just country. When I asked once if she was just “preaching to the choir,” she responded, “The choir still needs preaching.”

She held on to that belief into her 80s. In that last interview with Janiak, she extolled the purpose of theatre as “consciousness raising, exposing difficult truths, explaining the world.” Joan did all those things, and then some, for generations of fortunate theatregoers.

Misha Berson (she/her) is the former theatre critic of The Seattle Times and the author of several books on theatre, including Something’s Coming, Something Good: West Side Story and the American Imagination. She is currently a freelance writer and teacher, and a frequent contributor to American Theatre.