Mike Nussbaum, who rose to prominence as an actor in early plays by David Mamet and appeared in countless roles in Chicago theatres up until nearly the end of his life, died on Dec. 23, 2023. He was 99.

Most epitaphs are formulaic and lugubrious; and many, of course, are necessarily factitious, as there’s a deal of decency in “nil nisi bonum.”

Among the greatest epitaphs are those of the warriors at Thermopylae: “Go tell the Spartans, stranger passing by, that here, obedient to their laws, lie,” and that of Mel Blanc, who voiced all of the Warner Brothers’ cartoon characters: “That’s all, folks.”

A Civil War cemetery near my house in Vermont had several monuments proclaiming, “Mom, She Made Home Happy.”

As a friend and colleague of Mike Nussbaum for 50 years, I can suggest no more fitting nor respectful epitaph than that Kipling wrote for actors:

We counterfeited once for your disport

Men’s joy and sorrow: but our day has passed.

We pray you pardon all where we fell short—

Seeing we were your servants to this last.

Mike Nussbaum, rest in peace.

—David Mamet

Be Like Mike

Mike Nussbaum was my artistic father. I looked to him for support, guidance, and a deep and loyal friendship. I know he felt the same about me. In a film assembled for my anniversary at Northlight, he said, “I think of B.J. as my best friend in the theatre.”

In the past few weeks I have received so many phone calls, texts, and emails offering condolences on his passing. But in response to all of them, I’ve told friends that I was happy for him, because in the last year when I stopped by to spend time with him, he’d tell me he was ready to go. He told his dear friend Barbara Gaines, founder and former artistic director of Chicago Shakespeare, the same thing.

He directed me, I directed him, we acted together. Over a dozen plays at Northlight were graced with his gifts, beginning with our first production in 1975, Jumpers, directed by Frank Galati. Mike was then Northlight’s artistic director, and one of its founders, along with Galati and Greg Kandel, an MFA graduate at Northwestern. But he only stayed in that job for a year, because Mike was an actor, and that is what he wanted to do.

He was a consummate professional. He jogged when he still could, and famously did his daily 50 push-ups. He showed up off-book for first read-through, sending us all scrambling home to learn our words.

More importantly, it was his loyalty to the Chicago theatre community that inspired me. In 1983 while he was appearing on Broadway in Glengarry Glen Ross, I called him to ask if he would appear in my production of Quartermaine’s Terms at Northlight. He asked Annette, his wife, what she thought, and Annette said, “Yes! I’m tired of New York.” Coming back to the phone, he told me he was on. Imagine leaving Broadway to appear at a regional theatre in a converted grade school, where, as Mike Maggio, one of my predecessors, said, “The rent was high and the urinals were low.”

Because it was never about Broadway or Hollywood for Mike. For Mike it was about “the hang,” the work, and Chicago’s actors and audiences. He loved sitting in the green room laughing, dishing, being adrenalized by the next generation of actors, racing to beat John Mahoney to finish the Times crossword on Sundays. And always, always, telling the truth onstage.

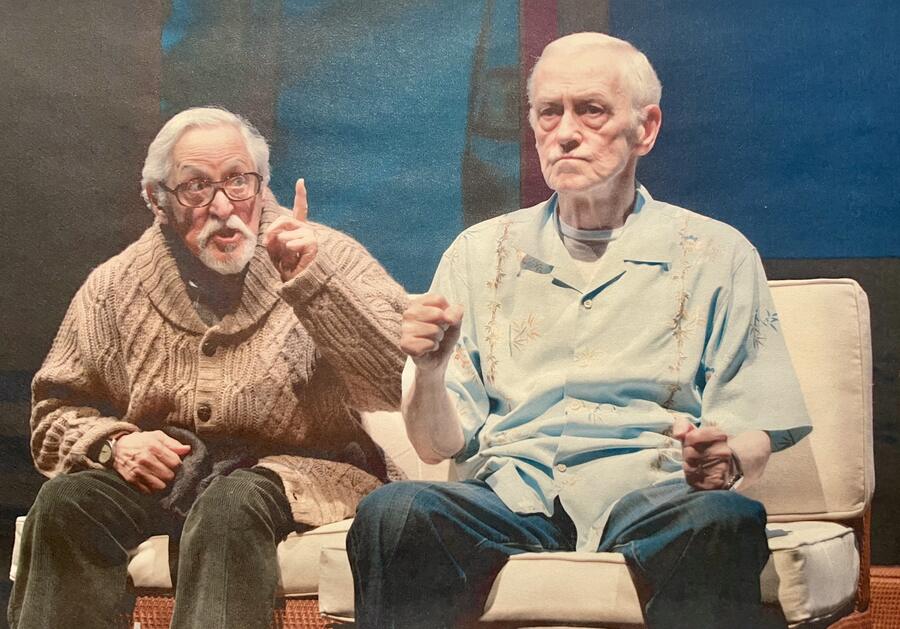

A dozen or so years ago, I realized I might not get to act with Mike again. So I reached out to David Mamet, whose plays had made Mike nationally recognized, and asked if he’d write a curtain raiser for Mike and me to read at events. He replied that he would “put on his velvet thinking cap,” and in two weeks I had a 15-minute skit called Pilot’s Lounge. I called Mike and asked what he thought. He said, “I don’t get it.” But when we finally got to read it, Mike got laughs! As usual, it was Mike’s chemistry, which Mamet knew so well, that sold the piece.

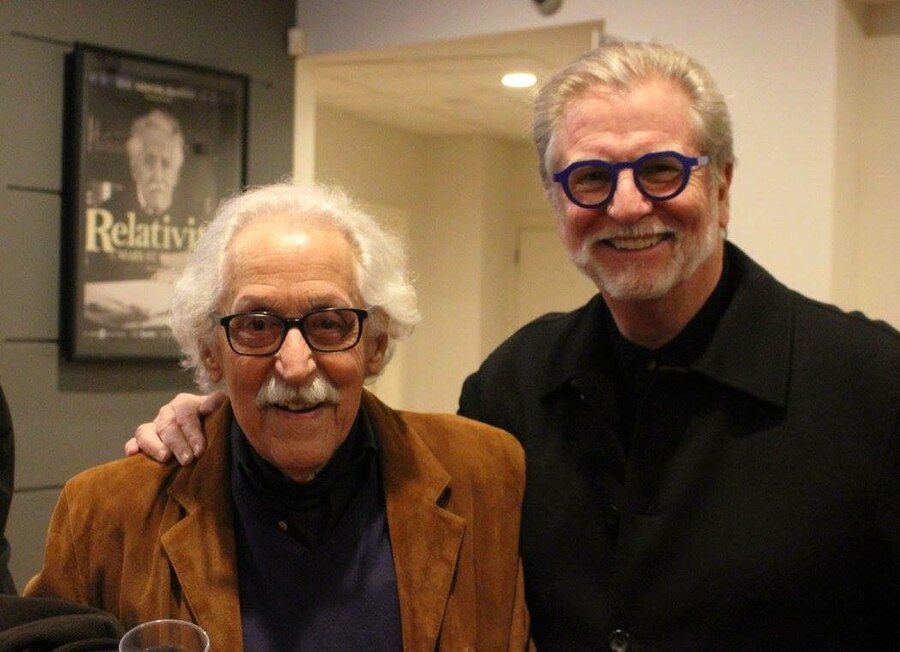

Mamet included a story about a leather bomber jacket Mike owned from World War II. The story was that Annette had the jacket cleaned, and in Mike’s view, the cleaning ruined it. Mamet wove that story into the play. It was a story Mike told David 40 years before in rehearsal, and David remembered it! Mike was so touched. In the last few years, I picked Mike up and drove him to a number of gatherings where we read the play, and people would ask for his autograph or he’d pose for a picture and it buoyed his spirits. It’s fitting that his last performances were in a Mamet work.

Once, in a production of Willy Holtzman’s play Hearts, Mike and I had a little disagreement over a moment in the play. Because I was the director, he accepted my suggestion. As I recall, one of the reviews lauded that moment, and the next morning, Mike called to thank me for insisting he play it that way. I had forgotten about it, but in his pure sense of fairness and justice, he wanted to set the record straight. That was Mike.

He and Annette raised their children Jack, Karen, and Susan that way: progressive, with an unerring sense of social justice, and with the determination to improve our world.

At nearly 100, Mike had come to the end. I brought him corned beef sandwiches and we would watch his beloved Cubs, but for the last visit he told me not to bring him anything. Regardless, I brought a script with a great role in it for him, just to keep him hungry about the work.

But he wanted to go; he said he was bored. If he couldn’t act, what was the point? In the end, he offered another lesson: to leave with dignity, with blunt honesty, and on his own terms. For Mike it was about the work, and his fellow artists. It was time.

He never missed an entrance, and he knew how to make an exit.

But his ghost light will always burn brightly for me.

B.J. Jones is the artistic director of Northlight Theatre in Skokie, Ill.