Today the unsurprising if still ominous news came down that the theatre critic Peter Marks took a buyout at the Washington Post; his last day is Dec. 31. Congratulations to him on an amazing run. He was and is a great critic and reporter (not to mention a mensch of a guy) who wrote with passion and insight and care for a long time at the Post. D.C. theatre was extremely lucky to have him. But his exit should also be an alarm bell and a moment to take stock, because, folks, when it comes to the theatre press, shit is grim. I know it has always seemed that way, but I don’t think people understand where we are.

I grew up in D.C., and as long as I can recall, there has been a chief theatre critic for the Washington Post: David Richards, Lloyd Rose, others. It’s been an important institution. People took this for granted; I assumed there would always be a theatre critic covering the scene. I don’t anymore. No one has been hired to replace Peter. The Post is struggling right now, and doubling down on covering Woolly Mammoth, for instance, is not going to be the first instinct of owner Jeff Bezos. Sure, there will be freelancers and takes and drips and drabs, and maybe even someone whose job is to cover the scene. But the trend lines are clear.

This is not limited to D.C. at all. If you look around the country, theatre critics are vanishing. Many big cities don’t have full-time theatre critics at papers of consequence. For artists—and I promise you this is not hyperbole—the choice in the near future is no longer between a good review or a bad one, a second take or a single review. It’s between something or nothing. The smart money is on nothing.

The discourse about critics in the theatre has been so mindlessly hostile for so long that most of the time, the sensible thing for people in the press to do is ignore it. The lack of respect for criticism is deeply embedded in too many theatres that were built in part on press attention. While adversarial distance is built into the relationship between critics and artists, the provincialism and entitlement of many theatre people’s attitude toward criticism is not serving them well. How many times have you heard someone say this review singularly killed a show and destroyed jobs, versus how many times you’ve heard someone say this review singularly made the show and created jobs? Neither is ever completely true, of course. But when it’s a success, people other than the critics take credit. When it’s a failure, the critic takes the blame. Okay, it’s part of the game and it’s fun to play. But reality is this: The theatre review as a form is, in my opinion, becoming an endangered species.

There are many reasons for this, but the fundamental one is that readers don’t want theatre reviews as much as they want other stuff—and while we used to not know this in detail, the Internet changed that. After years of observing the theatre and the press, and having once worked as a regular theatre critic and reporter, one thing I firmly believe is that the press understands the theatre a lot more than the theatre understands the press. So let me be clear: Not only is no one entitled to a positive review; no one is entitled to any review. There’s no rule that Arena Stage or the Public or any show on Broadway must be covered. And things change, faster now than ever.

If the Post doesn’t replace Peter, that will be a systemic change, a loss that will matter more to D.C. than ticket sales for any single show. Great plays and musicals will go undiscovered. Some movie or TV stardom will never happen. Actors will not be found by agents, managers, producers. D.C. culture will matter less.

The historical record will also suffer. Losing a theatre critic, in my opinion, matters more than losing a film or book critic, because theatre is ephemeral. My memories of shows I saw in D.C. as a kid have faded; the only thing that keeps them alive is the archive of reviews. Reviews mean that theatre art lives forever and can keep getting rediscovered.

There have been a lot of essays about why the theatre is in crisis and all kinds of explanations, but this is the big one that gets short shrift. This has been what’s been changing over the years: There is less and less press attention, positive and, just as important, negative. And surprise, the theatre is suffering. Maybe we critics did more than just kill jobs.

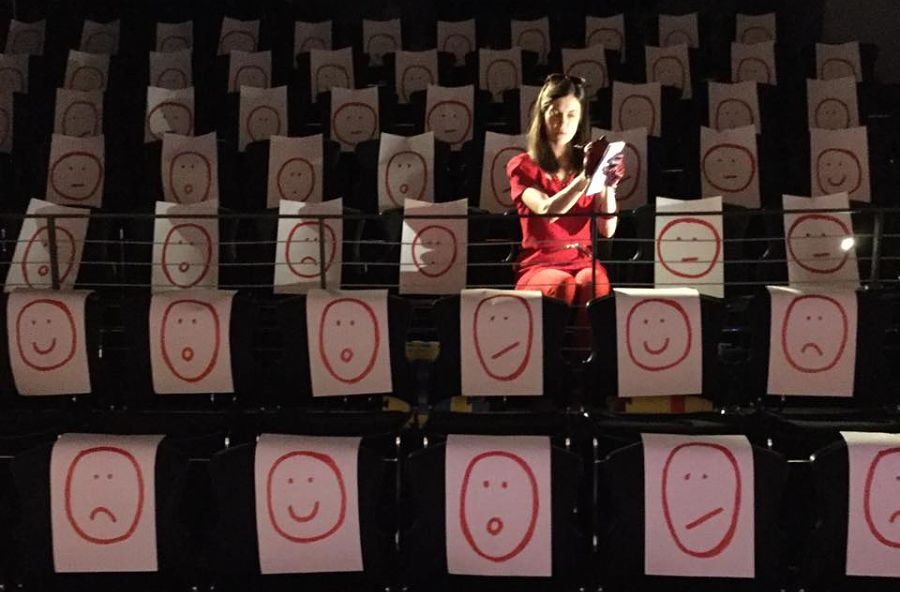

Around a decade ago, back in the days when I used to go on panels and talk about theatre criticism, I remember one where people were leveling some complaints, some legit, some not. And I told them: This is like being in the middle of a zombie apocalypse and fielding complaints about the quality of the dining. People are still complaining about the food, but the zombies have rampaged through another town and people need to wake up to it.

Criticism is vital to the heath of the theatre, and far too many of us—both in the press and the theatre—were too careless about that for too long.

Jason Zinoman is a critic at large for The New York Times.