Editor’s Note: In partnership with the Doris Duke Foundation and the Sheri and Les Biller Family Foundation, TCG’s THRIVE! Uplifting Theatres of Color initiative offered $1,140,000, equaling 46 grants in 3 categories, to U.S.-based (including Tribal lands and Territories) Black Theatres, Indigenous Theatres, and Theatres of Color (BITOC). In addition to the funds, 21 BITOC receiving RECOGNIZE category grants also participated in REBUILD, a learning cohort working with BIPOC consultants to strengthen their effectiveness in specific areas. The initiative was created with an advisory committee of 14 BIPOC theatre leaders and artists. To further uplift these companies, American Theatre magazine approached myself (Regina Victor, editor of Rescripted) and fellow cultural critic Jose Solís to curate and edit six articles highlighting the RECOGNIZE companies, with each of us guiding three pieces. It was our work to divide and then re-thread these companies together into articles with common themes, source writers and assign them, and edit their drafts, with American Theatre seeing to the final copy edit. These stories are examined through the lens of this year’s critically focused Rising Leaders of Color cohort (Amanda L. Andrei, Citlali Pizarro, and afrikah selah), as well as three Chicago-based writers (Dillon Chitto, Madie Doppelt, and Tina El Gamal). This six-part essay series showcases 21 examples of people doing the work, championing their culture, and finding creative solutions to generational problems. Thank you to Jose for being a wonderful thought partner in this project, and to Emilya Cachapero and Raksak Kongseng for their invitation and support.

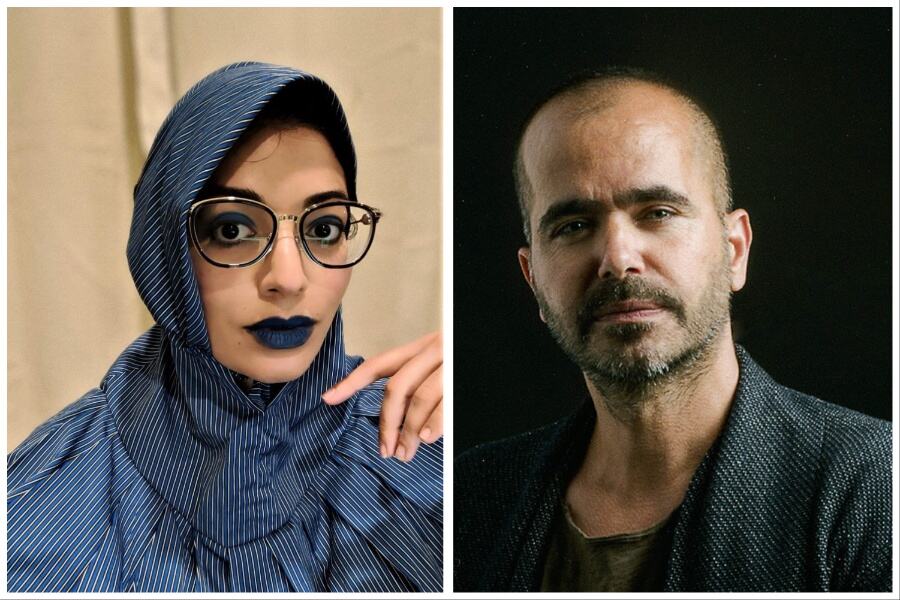

Wafaa Bilal’s medium of choice is his body. Tasneem Mandviwala’s is a paintbrush. They both love theatre.

A performance artist most well known for his interactive online works about international and interpersonal politics, Bilal focuses specifically on the tensions between the U.S., where he currently lives, and Iraq, where he was born and where, as he puts it, his “consciousness” resides. He is also an artist in residence with Golden Thread Productions, the first American theatre company devoted to plays from the Middle East.

Mandviwala is an abstract painter, cultural and developmental psychologist, and intersectional feminist. She also works for Silk Road Rising, a community-centered arts-making organization that focuses on highlighting Pan-Asian, North African, and Muslim stories through theatrical performance. She’s the advisory council coordinator for Silk Road’s Polycultural Institute, a think tank aimed at teaching the public about polyculturalism.

“In brief, it’s the idea that no culture exists in a vacuum—that we all affect one another,” Mandviwala says. “That very much speaks to how I relate to theatre as a visual artist. I don’t think any art exists in a vacuum. I think various art forms affect one another in quite beautiful ways.”

This is exactly what I—a theatre artist, journalist, and lover of art in all its forms—have gathered Mandviwala and Bilal on Zoom to discuss: their perspectives as performance and visual artists working with theatre companies. As artists who work across disciplines, from painting to installation art to video games, I anticipate that they’ll have brilliant insights on this topic. They do. But in conversing with them, it becomes clear almost immediately that I’ve been too literal and simplistic in my thinking. Instead of starting in on the practical differences between putting paint to canvas and bodies onstage, they want to talk about childishness.

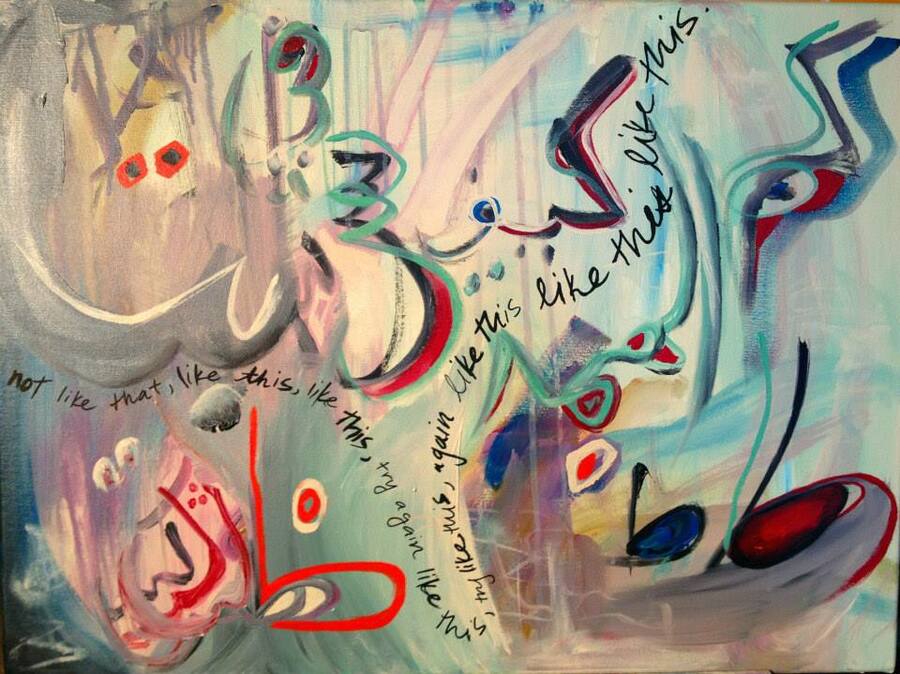

Most of Mandviwala’s paintings, upon first glance, seem a little “off” to the viewer. The subject of her painting “Desert” is in its name, but it’s not quite what the viewer expects of a landscape. It’s rendered by broad swirls of deep purple and the electric pink of grapefruit flesh. Dots and squiggles prevail—there are no harsh, perpendicular lines, just wobbly strokes and whimsical colors.

She likes it that way. She starts our conversation by telling me and Bilal about the importance of “play” in her work. Her paintings are intended to transport viewers to a state of childlike wonder and openness, which she believes is fertile ground on which to contemplate serious topics. Playfulness comes through in all of her paintings, especially those tackling subject matter like Islamophobia and American imperialism. It also comes through in the easeful vulnerability with which speaks about her work, and in her striking magenta eyeshadow.

It’s the same for Bilal, who centers the idea of “release” in his work, which explores political themes, like the devastation brought about by the U.S. war on Iraq. Bilal sees his lived experiences as proof that in moments of strife, people need release. After using his art as a form of political dissent against the regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, he escaped to a refugee camp in Saudi Arabia.

“Back home, during the war with Iran and then later on during the Gulf War, when Iraq was bombed and [I was] in the [refugee] camp, we used humor as a stress release mechanism,” he tells me. “We joked; we teased each other. And I think that stress release mechanism worked a lot. Because it reminded us we are human, above all.”

Humor is present in the art he makes today, in what he calls the “comfort zone” of the U.S. Less of a coping mechanism now, his art is something he uses strategically, he says, as a way to provoke U.S. audiences to think about the atrocities committed in Iraq “in their name.”

“It is really tough to engage them in political and social issues, specifically in political issues that are far away,” he tells me. “This has a lot to do with geographical distance, let alone the layer of isolation that is imposed by many other entities—the media, politics, the state. I find humor a great way.”

To these artists, then, the pursuit of play is serious. It’s both a human need and a tool for political engagement. It can also be an accessible, anti-oppressive approach to art-making.

“My work indirectly is anti-capitalist, anti-colonialist, and feminist as it strives to nudge viewers towards a more compassionate, inclusive, and less violent and aggressive way of looking at the world,” Mandviwala says. “Instead of trying to dominate the world around us, what if we instead accepted it lovingly?”

No painting of Mandviwala seems exactly as it “should,” such that a kind of unpredictable mischief threads through her work.

Our conversation ping-pongs from playfulness to political dissent and back again. We go from discussing the harsh material realities of our world to the soft ways we cope with them. We cover subject, tone, form. Mandviwala talks about paintings and Bilal talks about online, interactive art. And yet their insights build on and inform one another effortlessly.

With Mandviwala, as with her paintings, there are no real edges or harsh lines. All things connect, bleed into one another, harmonize. When she talks about her paintings, she transitions seamlessly from impassioned manifestos about childhood, to cultural psychoanalysis, to intersectional takedowns of the heteropatriarchy. It’s no wonder, she says, that she “struggles with self-descriptions in terms of labels.”

Bilal bristles at labels too. Don’t dare call him a political artist, for instance.

“What does that mean?” he asks me. “It really has no meaning to me.” His work is interpersonal and political, playful and serious. It is entirely driven by the social and political context in which it’s created as he works in installation, video games, online, and in-person. His works aren’t paintings, plays, or sculptures—they too refuse categorization.

So our conversation becomes sort of meta. I set out wanting to talk about the concept of interdisciplinary art. But I’m not discussing it, I’m witnessing it. “Interdisciplinary” is such a part of the DNA of each of these artists that they do not deliberately practice it as much as they embody it. They themselves defy discipline and categorization.

When we begin to talk about medium, Bilal and Mandviwala both agree that it shouldn’t be the primary consideration of the artistic process. They break it down for me: A work of art starts as a formless idea. The idea then dictates the form. For Bilal, the two most important questions are 1) who is the audience? And 2) what is the objective?

“If I want to reach a large amount of people, I cannot use a medium that has limitations in its approach. And if it is a personal, meditative project, let me use the right medium to meditate,” he says. “There is really no medium, to me, when it comes to an art project. The project determines that.”

Mandviwala agrees: “It’s really about the underlying idea, and in many ways, the medium becomes almost secondary to me.”

It’s secondary, but still important. It’s relevant insofar as different mediums—painting, performance art, and theatre are the ones we touch on most heavily—serve audiences and objectives in different ways.

Our conversation becomes sort of meta. I set out wanting to talk about the concept of interdisciplinary art. But I’m not discussing it, I’m witnessing it.

Bilal’s medium of choice is most often his own body. He describes his performances as “unmediated interactions between bodies.” This, he feels, is the most powerful way to elicit emotion in audiences. In Domestic Tension, his most famous work, which he also refers to as “Shoot an Iraqi,” viewers could shoot him with a paintball gun via internet livestream with the click of a button. The objective was to “raise awareness about the life of the Iraqi people and the home confinement they face due to both the violent and the virtual war they face on a daily basis.” And, of course, a kind of play was involved. He depicted the suffering of war “through engaging people in the sort of playful interactive video game with which they are familiar.”

He found it to be wildly effective. “When you put the body in front of other bodies, there are no barriers to deliver that message,” he says.

One key difference between his performance art and traditional theatre is that Bilal has never repeated the same performance twice. While in the theatre industry, repeating the same performance as many as eight times a week, sometimes for years, is commonplace, Bilal’s works are unique to the singular context in which they are performed: one time, one place, with all the social and political implications that each carries. In this way, his performance art is truly interactive. He’s after the kind of “raw emotion and reaction” between performer and audience that is compromised by attempts at replication.

Another difference between Bilal’s performance art and other forms, like visual art and theatre, is that his works have no end state. An actor bows after performing a written, revised, and rewritten final scene. A painter walks away from her masterpiece after the last stroke is put to canvas, her vision realized. Bilal, on the other hand, never claims, “I know how this project is going to end. If I say that, it means I leave no room for the people who are going to interact with it to interact freely. Then people are not going to be part of writing the script for the project,” he tells me.

His role as the performance artist, then, is not prescriptive. In a sense, he’s a facilitator. Rather than decide exactly how a work will unfold or impact an audience, he strives to maintain the integrity of a work by sustaining its interactive element and protecting its objective, rather than controlling it.

Visual art, on the other hand, like Tasneem’s paintings, is more contemplative, ripe for activating the “struggle within.” While the artist encodes an object, like a canvas, with meaning, the viewer decodes it based on their personal knowledge and references. It engages their inner life. And unlike theatre or performance art, it’s not time bound. Bilal and Mandviwala both note the transformative experience of standing in front of a painting for hours and losing yourself in it. And they agree that performance art and theatre can’t do that.

Still, we’re cautious of overlooking the interactive elements of visual art. Mandviwala’s eight young nieces and nephews can often be seen gently handling her paintings, getting a feel for the texture of dry acrylic paint. She encourages it. To her, paintings shouldn’t be untouchable relics hidden behind glass and security tape. “If a painting becomes something that is so distanced from an embodied experience, it loses some of its humanity,” she tells me.

It follows that embodied artistic experiences, like theatre, necessarily hold space for a fuller expression of humanity. Mandviwala and Bilal’s appreciation for the power of the art form is in part what led them to working with theatre companies like Silk Road Rising and Golden Thread Productions. This appreciation makes its way into their work, and that’s part of what led these companies to work with them.

“Listening to Wafaa speak and engaging with his creations undeniably brings about a transformation. I think his work tells stories in a very powerful way,” Sahar Assaf, executive artistic director of Golden Thread, writes me in an email.

If the power of painting is in its meditative impact, and the power of performance art in its interactive possibilities, then the power of theatre, to Bilal in particular, is in its ability to mobilize.

“I’ve always thought of theatre as really the medium that mobilizes people,” he tells me. “It is the medium that galvanizes issues and brings people together. It’s the medium of emotion.”

It’s also a medium of play. In her work with Silk Road Rising, Mandviwala draws on the similarities she observes between abstract painting and theatrical performance. For her, it all comes back to playfulness. “No matter how good the actor is, the performance will never be the same,” she marvels. “To me, that harkens back to the authenticity of the child.”

Mandviwala’s insights bring us back to the similarities among the art forms. As she speaks, I consider that there’s an authenticity in Mandviwala’s style that is almost theatrical. No painting of hers seems exactly as it “should,” such that a kind of unpredictable mischief threads through her work. Each abstract cityscape has its unique quirks: too-loud color schemes, unsteady strokes, kaleidoscopic proportions. It’s like a musical.

Her colleagues at Silk Road Rising agree. In addition to working on their Polycultural Institute, her paintings are also heavily featured on the organization’s website.

“[Mandviwala’s paintings] align so beautifully with our mission and aesthetic—they are theatrical and conscientious,” Jamil Khoury, founding co-executive artistic director of Silk Road Rising writes me in an email. “Tasneem’s art exudes connectivity and relationship, poetry and possibility.” Malik Gillani, Silk Road’s other founding co-executive artistic director, agrees. “Tasneem’s art is deeply spiritual, profoundly Muslim, and quintessentially Silk Road,” he writes. “It evokes prayer, wonder, and ecstatic joy.”

So we end the conversation where we began: with joy, ecstasy, play. It occurs to me that the act of theatre is play. No matter the subject matter or tone, putting on a piece of theatre is, in a sense, playing dress-up. Mandviwala and Bilal agree, and this is part of why they appreciate the art form; it’s a game of pretend that it happens, as Bilal puts it, in a “pretend zone,” where the rules of reality don’t necessarily apply. People have permission to engage with ideas without fear of social judgment. It opens up possibilities that don’t exist outside of the theatre. At its best, it can help people rethink the way they engage with the world around them, creating new systems of relation.

“In that childlike play, you’re no longer in reality, so you have to take the time to come up with a different system to make sense of what you’re seeing,” Mandviwala notes.

Ultimately, these two artists are so thoughtful and knowledgeable about art across various forms and disciplines because, in their artistic ethos, the ideas take precedent. They submit to an idea and follow it wherever it leads them: to the easel, the blank page, the stage. The values undergirding their ideas are what stays with me long after we end the Zoom call.

“I’m motivated by larger themes of humanity and ways that we are all connected, and ways that we might change, suffer, and experience joy,” Mandviwala says.

It’s similar for Bilal. After spending years engaging with conflict and tension in his work, he’s started looking to restoration and transformation with projects like 168:01, an installation and performance piece aimed at restoring the University of Baghdad’s library, where over 70,000 books were destroyed in the war.

“Iraqis on the ground need something different, other than alerting or engaging people about the atrocities committed against them,” he told me. “During the sounds of the guns, the only thing we cared about was how to protect ourselves. What happens when the guns fall silent?”

Citlali Pizarro (she/her) is a writer, producer, and theatre artist based in New York City. She currently works in producing at the Public Theater.

Want to learn more about the THRIVE! grant recipients? Check out this new video featuring them here.