When journalist DT Max told Stephen Sondheim that he was both “never much of a Hitchcock guy” and was unfamiliar with the Master of Suspense’s gem Shadow of a Doubt, the composer/lyricist seemingly could only muster the following: “Oh man, oh man, oh man.”

Everyone knows Stephen Sondheim loved puzzles. But his second greatest love seemed to be the movies. So deep was his love of cinema that in the same conversation, which appears in Max’s thin book Finale, Sondheim quizzed the writer on what title opened the very first New York Film Festival, the popular and prestigious site of both international and domestic offerings of cinema that occurs annually at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and which began in 1963, founded by Richard Roud and Amos Vogel. The answer: Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel, an acerbic satire about a group of wealthy people who are inexplicably unable to leave a room, and one of the source texts (the other is Buñuel’s later The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie) for Sondheim’s final “completed” musical Here We Are, with a book by David Ives, which opened at The Shed on Oct. 20 (and runs through Jan. 21).

In its current state, Here We Are feels like a final parlor trick from Sondheim, in that it begins as one thing and slowly transforms into another. While a group of insufferable and extremely wealthy friends arrive at the doorstep waiting for brunch to be served to no avail, the gang of tracksuit wearing entrepreneur Leo (Bobby Cannavale), talent agent Claudia (Amber Gray), vapid Marianne (Rachel Bay Jones), doctor Paul (Jeremy Shamos), lothario Raffael (Steven Pasquale), and aspiring revolutionary Fritz (Micaela Diamond) are left to sate their appetites elsewhere. From one aggressively cool and slick restaurant to the next, their hopes for food are constantly derailed because the place is out of food or the owner has died or the food is fake. When they finally arrive to dine at Rafael’s embassy digs, they discover they are unable to leave the room, and are thus forced to confront the material nature of their lives and what it would be like to live without all of it. All of the splendor and chic and glamor, stuck with each other and their own well of thoughts. Trapped with their own sense of being.

Watching Here We Are at The Shed has much the same tickling irony of watching the Thomas Adès and Tom Cairn opera adaptation of The Exterminating Angel at the Met, as both are ostensibly satires of their own audience and their own venue; both the Met and The Shed are built upon a fraught, unequal class divide. But while The Exterminating Angel all but defanged Buñuel’s vicious critique of upper-class hypocrisy, Ives and Sondheim keep it intact for the most part, though it ultimately comes into conflict with their boomer sensibility. Fritz, a real nepo baby if ever you saw one, can rail against the elite, but Here We Are is quick to note that they are nonetheless the benefactor of all its resources.

Yet the fact that Sondheim’s final piece is a satire, and thus must start with archetypes and caricatures, presents an entertaining challenge to the audience, both for lovers of the composer/lyricist and for the unininitiated: Can you care about such callous people, who are, at the start, meant to be one-dimensional jagoffs? It’s not unlike the task he and James Lapine set for themselves in Into the Woods, where fairy tale characters have to confront the complexity of reality outside of the storybook. Buñuel’s goals in The Discreet Charm and The Exterminating Angel had less to do with humanizing his characters; they were instead meant as absurdist funhouse reflections of a society he deemed to be on the brink of collapse, with the sounds of war threatening to break through the theatre. Now that both collapse and war are increasingly our reality, this bitter satire arrives with fresh relevance, albeit reframed by one of the great humanist theatremakers of our time—an artist whose struggle to understand people pushed him to view them through intricate games and puzzles of form, technique, and content.

For the most part, Here We Are succeeds at this gambit. A somewhat flawed show where the missing pieces are obvious, it nonetheless engages seriously and thoughtfully with characters that most audiences, no matter how self-aware, might try to write off. And the score feels a bit like a hodgepodge of Sondheim’s greatest hits, with elements of Company, Follies, Merrily We Roll Along, and Passion thrown in for good measure. Here We Are is a final sendoff with a wry smile and a wink, even amid oncoming apocalypse.

But what does Here We Are say about Sondheim’s lifelong cinephilia? A reading of his work, as well as his biography, shows that its roots run deep. According to biographer Meryle Secrest, Sondheim and Oscar Hammerstein’s son, James, went to the movies in Doylestown, where the young Stephen was informally under Oscar’s tutelage. Of those visits, and trips with his father to see films at Radio City Music Hall, Sondheim told Secrest, “During my formative years, movies really molded my entire view of the world.”

It would be at the movies, for instance, that he would hear the foreboding and morbid thrums of Bernard Herrmann’s score for Hangover Square, a 1945 noir whose music would later inform much of the composer’s career, in particular the intensity and cynicism of Sweeney Todd. And before young Sondheim set about writing songs, he took a stab at filmmaking, crafting little home horror pictures on a Bolex. After collaborating with Leonard Bernstein on West Side Story, Sondheim roped Bernstein and his wife, Felicia Montealegre, into making short films on his 16mm Ciné Kodak camera, remaking boxing movie Golden Boy and the Joan Crawford-starring Humoresque. He would eventually make a 10-minute version of Puccini’s Tosca in 1961. It’s easy to understand the affinity between filmmaking, with its intricate, puzzle-piecing together of different components, and that of music and lyric, character, and situation that would become his life’s work.

Sondheim the filmmaker was not to be, in part because, as he wrote to his friend Ford Schumann in a letter recounting his visit to the set of John Huston’s film Beat the Devil, starring Humphrey Bogart, there was too much “waiting.” But his time playing poker with producer David O. Selznick and learning about filmmaking on the set of the Huston film stayed with him. For one, he still had enough interest in film to write the screenplay for the 1973 film The Last of Sheila with Anthony Perkins. This wicked murder mystery satire, set among a group of callous Hollywood types, was inspired by the games and scavenger hunts he and Perkins would throw in New York with friends.

Cinema kept seeping into Sondheim’s work, even as he put it to the side: in his unfinished novel Bequest, which he said was the product of “watching too many Bette Davis movies,” and in a musical version of Vincente Minnelli’s The Clock he once tried to pitch, to little avail, as well as an adaptation of Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House. You can see the fingerprints that the movies had on Sondheim’s work as early as Saturday Night, the flop 1955 musical; the song “In the Movies” lovingly mocked the dissonance between movie stardom and real life, and the follies of those who seek fame.

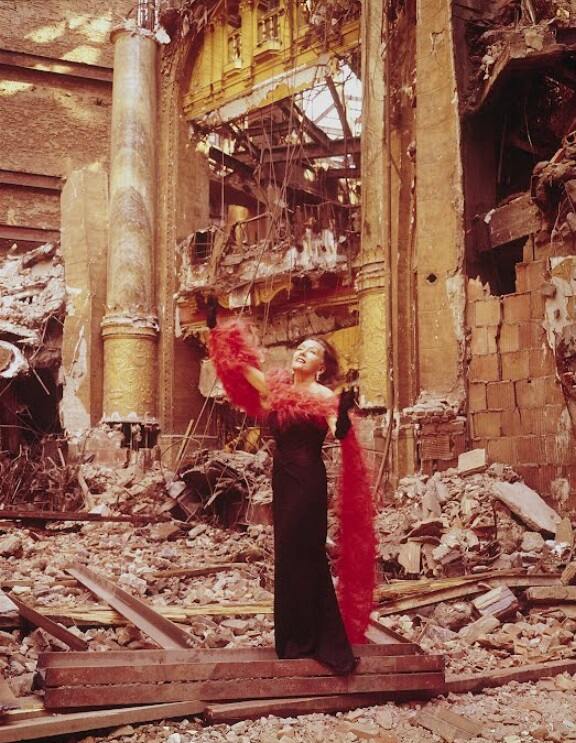

A Little Night Music was based on Ingmar Bergman’s Smiles of a Summer Night; Passion was based on Ettore Scola’s Passione d’Amore. And, though it was based on a stage play, George Furth’s adaptation of Merrily We Roll Along has at its center a composer-turned-movie producer. Even Follies, that quintessential valentine to the stage, was originally inspired by a photograph of Gloria Swanson in the rubble of the Roxy Theatre, a motion picture palace. And the furious transformation of Mama Rose at the end of Gypsy was supposed to, according to Sondheim, have the “effect, we hope, equivalent to a horror movie.”

Sondheim composed the score for French New Wave filmmaker Alain Renais’s Stavisky in 1974. It was the only instrumental score he would do solo (and, according to Secrest, without the aid of pot!), though he would later contribute to the score for Warren Beatty’s Reds and win his only Oscar for “Sooner or Later,” written for Beatty’s Dick Tracy. After his heart attack in 1979, Secrest writes that Sondheim “bought himself a stationary bicycle and, to relieve the boredom, pedaled his way through dozens of old movies.” In 2003, Sondheim served as the guest director of the Telluride Film Festival, programming movies like French director Julien Duvivier’s La Belle Équipe and The More the Merrier, as well as Krzysztof Zanussi’s The Contract. In The New York TImes, Elvis Mitchell noted, as did other biographers, that Sondheim’s passion was primarily for older movies and “the old-school presentational movie acting of the 1940s and 1950s, while being attracted to the theatre for the new realism that was coming to the stage via the Method.”

This long filmographic résumé, though, says little about the cinematic qualities of Sondheim’s work (which, lest it be forgotten, was also aided by directors like Hal Prince, James Lapine, and, now Joe Mantello). Company’s sardonic view of middle-class life precedes The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie by a few years, but its scrambled vignette structure and light absurdism nevertheless has traces of Buñuel in it. If the crux of The Discreet Charm is the notion that pleasure, especially for the wealthy, is deferred ad infinitum, Buñuel’s DNA can be found in the way that Company’s cocktail of marrieds, singles, and everyone in between seem to be resting their notion of pleasure and fulfillment on someone else, and are therefore unable to achieve it. Think of Bobby meandering from scene to scene, unsure where he stands with any number of his friends, and those same friends predicating their own happiness on whether Bobby is married or not.

And Follies was built upon the crumbling edifice of classic Hollywood as much as it was on the vestiges of Ziegfeld, with “I’m Still Here” influenced by the life of Joan Crawford and sung by Yvonne de Carlo. In fact, there was talk of making it a movie which, as opposed to taking place at a reunion of Weissmann Follies dancers at the theatre where they performed, would take place on the last night of MGM, documenting in meta-textual real time what had happened to the old studio system. In that version, the idea was to play old movie clips alongside the big names they were trying to get for the roles (including Crawford, Swanson, Davis, and Elizabeth Taylor), but these offers all fell through. The resulting show feels at times like a Robert Altman movie, with our attention drifting from one conversation with a former dancer to the other, and only the unhappy two couples to anchor us. Added Sondheim, “I was much influenced in those days by the movies of Alain Resnais, and I think Follies was probably more influenced by Last Year at Marienbad than anything else. It had to do with time.”

Time, and cinema’s unique ability to manipulate it, is the element that appears to have most impacted Sondheim as an artist. Though Merrily We Roll Along’s first life, as a play by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart, featured the show’s reverse chronology, one could argue that this conceit was perfected in film, with Oldřich Lipský’s 1966 Czech comedy Happy End giving Sondheim, Furth, and Prince a roadmap. Into the Woods can be clearly read as a riposte to the Disney-fication of fairy tales. But more importantly, the temporal dissonance between the stories we grow up with as children and the realities of our adult lives, when we must confront complexity, feels deeply embedded in the show.

Here We Are has an elastic relationship to time and space, with the elaborately spare scenic design by David Zinn and lighting design by Natasha Katz sliding in or descending from the heavens with acid glow neon. In the first act, references are made to what time of day it is, as the group traipses from one restaurant to the next, but the lighting evades exactitude to give the impression that it could be any time and any day, and certainly past brunchtime. When all the characters find themselves trapped in a glamorous room of black and gold surfaces, Here We Are, with fewer songs and less music than its first act, takes on a quasi-durational theatre approach, accentuating the way these people are truly caged for hours and hours, possibly days or weeks. They switch positions in a few (flawed) throwbacks to “Tick Tock” from Company to show the passage of time, but the second act’s true approximation of the tedium of waiting invites the audience to consider what it’s like to wait for something to happen on the stage while everything is falling apart outside. Though Sondheim is more of a sentimentalist than Buñuel, their aim—to transform the space in which audiences experience art—is similar.

Cinema’s great power to Sondheim was its ability to remake the world in the artist’s image, and to turn the place where it’s viewed into a safe haven, an escape, a memory, a nightmare, a painting, or a journey. In the shimmering light from the screen, Sondheim saw how movies could reflect, refract, and deconstruct our lives and desires and anxieties. That it was done by assembling disparate and random elements, all pieced together to create something extraordinary and astonishing, taught Sondheim that theatre could do the same thing, albeit with different tools.

After his death, his list of 40 favorite movies (originally culled by The Sondheim Review) began to circulate on the internet. It boasts a wide array of works, ranging from The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes to the Soviet-produced adaptation of War and Peace. Apart from affirming his omni-voracious tastes, the list pointed to the way in which his favorites—from the horror of Gus Van Sant’s Elephant to the humanity of Robert Bresson’s Au Hazard Balthazar—form another set of puzzle pieces, through which he sought to better see and understand the world and ourselves. Sondheim’s great achievement, on display right up through his last work, was to adapt the tools and effects of both theatre and cinema, placing them in dialogue with one another, so that every show is opening doors, singing, “Here we are.”

Kyle Turner (he/him) is a freelance writer based in Brooklyn. His writing has been featured in Slate, GQ, W Magazine, The New York Times, and he is the author of The Queer Film Guide: 100 great movies that tell LGBTQIA+ stories, published by Smith Street Books and Rizzoli.