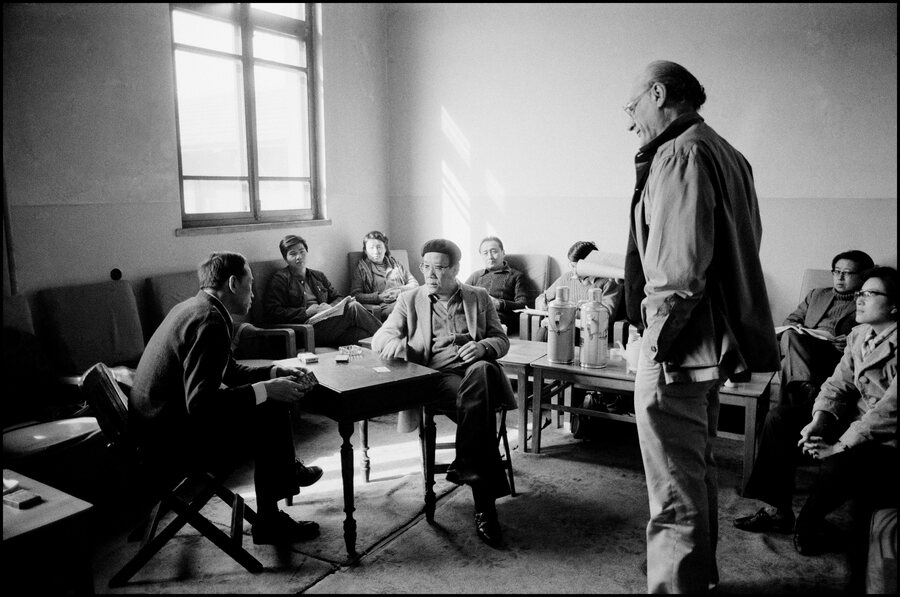

In Jeremy Tiang’s Salesman之死, the main character is the one whose role is to disappear. Shen HuiHui, played by Jo Mei, is a 27-year-old Peking University professor tasked with working as Arthur Miller’s translator during the rehearsal process for his 1983 production of Death of a Salesman at Renyi Theater Company. Tiang’s behind-the-scenes play, now in a Yangtze Repertory Theatre production at New York City’s Connelly Theater (through Oct. 28), follows Miss Shen through the winding roads of communication and translation, as she completes cartwheels of mental dexterity and linguistic skill to bridge the gap between the American playwright and his company of Chinese actors. (Chinese actor Ying Ruocheng translated the play itself, but as he was also playing Willy Loman, he was not able to handle the translating needed throughout the process—a job that fell to Miss Shen.)

The play is thus inherently bilingual, with projections of subtitles switching between Mandarin and English. But it’s not just English and Mandarin—it’s Brooklyn 1940s English and Beijing 1980s Mandarin. Idioms, metaphors, and turns of phrase are constantly being turned around and reexamined, taken literally, and redirected.

The audience spends 100 minutes with Shen, the actors, Miller, and the designers and crew of Renyi, watching them untangle and decipher this classic together. Note that “together” in this context does not necessarily mean “harmony.” There is instead a cacophony of argument and discussion, with so many layers of conversation that even the screen hosting the subtitles gets overwhelmed and saturated with a surplus of text. You might not understand all of what they are saying, but you can gather what’s being said.

When Shen Huihui explains in the play how she was able to become both fluent in English and knowledgeable on Arthur Miller’s plays, she describes it as “a stroke of luck,” meaning the accumulation of happenstance that led to her involvement in the Renyi production. Indeed, every theatre performance requires a bit of serendipity. For every cast member, cue, and audience member to meet in a singular space at the same time and share a collective experience is nothing if not the culmination of both luck and hard work. So it’s interesting to think about how Shen, who worked so hard to perform miracles of translation throughout this historic process, has largely been forgotten until now.

Jo Mei, who plays Shen, put it aptly. “I think it’s a testament to how well she must have done her job, that it seemed like everything happened without her,” said Mei. “Although that’s often like what happens with women, right?”

That erasure is something Tiang, the playwright, is actively working against. As the translator of more than 20 books from across the Chinese-speaking world and co-editor of Violent Phenomena: 21 Essays on Translation, he hopes with Salesman之死 to make this work more visible. “There’s this idea that if we do our jobs as translators properly, then you don’t notice us at all, which I don’t think is true,” he said.

Indeed, as his play invites us to witness the process unfold as actors move across languages, genders, ethnicities, and ages, Salesman之死 does not show us the rousing, captivating, smooth Renyi production of Death of a Salesman. Instead we see the hiccups. The audience, Mei said, is “seeing how badly it could have gone, or how difficult the process was to create something that seemed effortless.”

The layers of translation, history, and meta-theatre in Salesman之死 might be compared to a popular vegetable. As dramaturg Annie Wang recalled, “We were joking at the opening night party about what vegetable our show would be, and the immediate resounding answer was a cabbage: many layers, endlessly versatile, and resilient. I think of Salesman之死 as a play made of many distinct layers, connected at the root of the 100 minutes we spend together in the Connelly Theater, which is also the Renyi Theater.”

This metaphor was inspired by a moment in the play when Shen and Inge Morath—Arthur Miller’s American wife (played by Lydia Jialu Li), who is trying to learn Mandarin—looks at a quote on the chalkboard, “一颗菜精神”, which Shen translates as “The Spirit of One Vegetable.” Shen further explains the quote to mean that “this production is like a single vegetable—a complete creation that cannot be separated.” Morath retorts that in fact one can cut a vegetable. But the essence of the quote remains true. After all, what happens when you cut a cabbage? You get to see the layers. So it is with meta-theatre: Whether or not an audience member is able to keep up with the play’s multilingualism, they can see the many pieces that came together to create this iconic production.

For his part, Tiang invokes a different culinary analogy: the Singaporean concept of Rojak, which is also the name of an iconic Southeast Asian salad.

“Rojak is the metaphor Singaporeans have instead of the melting pot, because in Rojak, every element remains itself. They’re all tossed together and there’s a sauce that binds them, but each element is separate. It’s not melting into anything. It retains its individuality.”

Salesman之死 ultimately proves that the power of theatre is not always the story onstage but the people behind it—the ones who spend weeks arguing and trying to understand one another, and through a thousand strokes of luck and hard work come together to tell a story. Understanding is not a destination, but an effort taken on by every pair of eyes and hands that cross a production. When audiences witness Salesman之死 , I hope they are able to let this process wash over them and really, truly, simply listen. There is so much to hear. Even in what is not understood.

Esmé Maria Ng (they/she/he) is an early-career theatre creator/administrator/educator whose work focuses on the complexities of Asian American history, queerness, and the family unit. Currently Esmé is a teaching artist with Girl Be Heard, the outreach and engagement associate at Classic Stage Company, associate producer of Breaking the Binary Festival, and a freelance writer and dramaturg.