“Did you see this?”

This common question used to refer to the latest production making waves in Chicago. But now our group chats and email threads crowd with the latest takes on our theatre industry. We see news of companies closing, losing their spaces, pausing operations, reducing seasons, laying off staff, and putting out urgent calls for donations. It all has the feel of a crash you can’t look away from.

Something about the severity has engaged not just those in the profession but friends and family far outside our rehearsal walls. It took a global pandemic for people to begin to see what has been happening behind the scenes for years. Theatre—the art form, the industry, the people who make it—is suffering.

Coverage in the Washington Post, New York Times, Variety, The Guardian, Chicago Tribune, and Chicago Sun-Times, among others, sometimes read as if the problems afflicting the theatre are new ones that began with the pandemic shutdown. Of 13 articles, essays, and op-eds published in July and August 2023 that we reviewed in some of our nation’s largest publications (not including the coverage in this magazine), nearly all spoke primarily to consultants or executive leadership and board members of large theatre companies, and some cited no outside perspective beyond the writer’s. The average annual revenue of the 25 theatre companies profiled in these articles was over $21 million, and nearly all writers were white cisgender men, professionals of power and privilege through their position in the industry in leadership roles at a theatre, foundation, or newspaper.

By focusing their coverage on larger institutions and established voices, this deluge of articles about the theatre industry only perpetuated the inequity that has brought our industry to this point of distress. A longer view of the context, history, and structure of our industry shows that the reason we’re at this crisis point in the first place is that we’ve operated the same way for so long, without thought of the long-term consequences. Finding solutions to such a complicated crisis, of course, will never be one-size-fits-all: Theatre models range from storefronts to regional, nonprofit to commercial, and what works in Chicago can’t necessarily be copied in South Dakota or California without adjustments for local dynamics, economic realities, and labor laws. But if we truly want to address the current state we’re in and find a better way forward, we need to include small and mid-size theatres in the conversation, look at economic history, and speak to the artists and workers, not just the administrators and board members. In short, we need to dig into the root causes. As writers and artists based in Chicago, we are well positioned for this inquiry, as innovations are happening right here that provide possibilities toward working more equitably and with an abundant—albeit realistic—mindset.

“We have accepted that the only version of organizational success is infinite growth. As a sector we have accepted this—and it’s not true.”

Kate Piatt-Eckert

Let’s start with some history. In 1989, American Theatre magazine published an essay titled “Designing Money” by Marjorie Bradley Kellogg, about the financial state of theatrical designers. In it she said, “As costs soar and fees don’t, the freelance designer (and most of us are freelance) can be working nonstop and still be unable to clear a living wage.” The essay could have been written today—with the glaring exception that the $3,200 average regional theatre scenic design fee sounds enviable.

The pay rates were certainly bad in 1989, yet in the years since they haven’t managed to keep up with inflation, let alone grow at the same rate as the cost of living or the cost of designing. In fact, the average fee for a scenic design would have to be over $14,000 to have kept up with the sad and stagnant growth of the minimum wage ($3.35 in Chicago in 1989, currently $15 for non-tipped workers). When asked how this matched up to average pay rates for scenic designers today, Matt Walters, the Central Region Business Representative for United Scenic Artists Local USA829, IATSE, explained that member theatres of the League of Resident Theatres (LORT) generally don’t pay above the minimum rate in the collective agreement anymore. “Without getting too into the weeds,” Walters said, “I would say that the average fee in regional theatre for scenic design is probably $6,000-$7,000 these days, but the range is absolutely huge.” He added, “The ‘average’ doesn’t really tell the whole story, in my opinion. The disparity does!”

Disparity in many ways does tell the story. Many artists have not been able to grow a personal safety net, or even continue working as artists, because they’ve essentially subsidized the industry with their labor for most of their career. As a 2019 UNESCO study put it, “The largest subsidy for the arts comes not from governments, patrons, or the private sector, but from artists themselves in the form of unpaid or underpaid labour.” The pandemic put extraordinary pressure on a system that was already being held together by those with the least ability to adjust and adapt, and the shutdown left freelance workers with few choices. When places of employment shut down, most moved on and into jobs in other sectors. With their departure, the industry not only lost some of its most valuable talent and institutional knowledge that will take years to replace—it also effectively lost one of its largest subsidies.

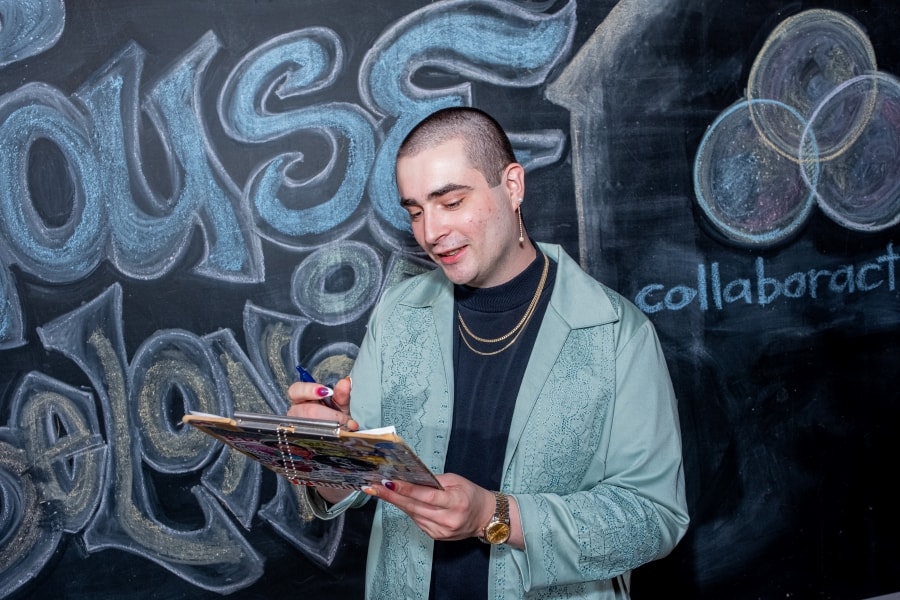

“People say making art is a privilege, but paying your bills isn’t a privilege,” said Zachary Crewse, a freelance stage manager and producer in Chicago. Crewse has worked in a variety of theatre and dance companies, including at Collaboraction Theatre Company, which uses On Our Team’s Pay Equity Standards (co-founded by one of this piece’s co-authors) and has a transparent Equitable Pay Policy that determines compensation levels with a minimum of $19.25/hour for all workers within the organization.

“I have also worked at places where it’s quite the opposite—where I know the artistic director is making nine or 10 times my salary,” Crewse said. “It doesn’t feel good. When you’re the person who is making the play happen and working the long hours and you don’t see much more than minimum wage, and then the leaders say how ‘we’re all in this together’…It’s not the same when you’re living paycheck to paycheck.”

Underpaid arts workers aren’t unique to theatre. Museum workers, musicians, and TV and film workers all face similar structures. As we saw with the summer’s entertainment strikes—until writers, though not yet actors, struck a deal with Hollywood producers—arts workers are collectively organizing across mediums to address similar systemic issues.

Best Practices for Who?

Although we’re still contending with the cliché of the starving artist, we don’t have to perpetuate it. Theatre companies that pool resources can remain in the black, as such partnership requires centering access and reevaluating what success looks like. Co-producing, co-working, co-publishing, and more are modes of collaboration that can foster sustainability and provide innovation.

Kate Piatt-Eckert got her start in Chicago theatre working as a stage manager and then as a shared bookkeeper for many smaller and mid-sized theatre companies through a program run by the League of Chicago Theatres. While that program at the League ended long ago, in her current role as the director of the Mission Sustainability Initiative (MSI) at Forefront, which supports nonprofit mergers and partnerships in Illinois, Piatt-Eckert has seen a lot of interest and potential “in theatre to both decrease costs and increase artist support” through collaborative back-office services and organizational partnerships. As she works with organizations to facilitate collaborations and partnerships, she wants the theatre sector to “expand our definition of organizational success.”

“We have accepted that the only version of organizational success is infinite growth,” said Piatt-Eckert. “As a sector we have accepted this—and it’s not true. I’m excited about looking at ways that we can celebrate many life cycle changes, recognizing that a world in which all theatres continue to grow forever doesn’t make a lot of space for new theatres to start. We should recognize a time when the structure is no longer serving the art and find a way for the art to find a new structure.”

Chicago is famous for its heavily mythologized storefront theatre model, in which friends gather and produce art with nothing more than a found space and their free labor. Looking more deeply and clearly into this history, one finds some harsh edges, not to mention a legacy of low pay and union strife. Belying the myths, some theatre companies have always been committed to paying their artists. Take Rivendell Theatre Ensemble, for example, a 30-year-old Equity company centering the untold stories of women. Founder and artistic director Tara Mallen said that union status was a priority from day one.

“In Chicago, it always seems like a choice,” Mallen said, reflecting on Rivendell’s itinerant beginnings. “You can either have a space or you can pay your artists.” In the 1990s and early aughts, she recognized that her company could not manage both. She decided to prioritize paying her people before investing in a structure. Later, through Mallen’s relationship-building in the Edgewater neighborhood, and almost by chance, Rivendell later became a resident theatre company in a family-owned building with an accommodating landlord.

Across Chicago and the country, we’ve seen some companies double down on capital campaigns, forging ahead with plans for new buildings or renovations, even amid mass layoffs and season suspensions. One op-ed nearly recognized the correlation in theatres experiencing financial distress with recent capital campaigns and calls for better labor practices, noting, “This is a systemic problem; that $117 million that went into new buildings could, after all, have gone into artists’ salaries.” But that was directly followed by, “Except, of course, that is not how the real world works.”

There are a lot of options on how to operate in the “real world.” One example is American Blues Theater, which works to put “people first, things second.” American Blues committed to pay equity before committing to a $7.8 million capital campaign for the land purchase and new construction of their permanent home. Their transparent Pay Equity Policy borrows language from On Our Team’s Pay Equity Standards and is the result of pay equity work American Blues has been doing since 2013, and more deeply since 2019. In the past, Gwendolyn Whiteside, artistic director of American Blues, said that when the organization was looking for information on labor issues and best practices, they had reached out to “older, more established institutions for their contracts and guidance,” including on things like calendars and rehearsal schedules, worker contracts, IRS classification, and workers’ comp audits for insurance. But, Whiteside explained, “We had wrongfully assumed their processes were best practices.”

Many recent op-eds have lamented that the audiences aren’t coming back, citing theatres’ supposed social justice content as the reason for audience attrition.

“I scratch my head when I see that opinion—I wonder what that means,” said Ericka Ratcliff, artistic director of Congo Square Theatre. “I also just want to know where the data is?”

When we as an industry only look to the experiences and processes of, as Whiteside put it, “more established institutions,” we not only perpetuate power structures that may not serve us—we also miss out on new models that may offer solutions. Across the industry, in fact, average audiences “haven’t been coming back” for decades; the decline in ticket sales and subscriptions has been well documented. In 2019, SMU Data Arts published a study titled Theatre at the Crossroads, which noted that attendance steadily declined from 2004-2017 by 8 percent.

But while that history and averaged data is necessary context, not every theatre company is experiencing that decline. Are we taking the opportunity to learn from the companies that are seeing rising ticket sales? Are audiences actually passing on productions with so-called “social justice content”?

Congo Square, for one, is seeing its post-pandemic audiences grow, Ratcliff said. She attributed this in part to the engaging work the company is producing on difficult topics like medical racism and access to housing in their recent productions of Lisa Langford’s How Blood Go and Inda Craig-Galván’s Welcome to Matteson!, respectively. “Our audiences want to see that,” Ratcliff said. “They want to be in a theatre where their voices and the things that they care about are being represented.”

Similarly, Mallen said Rivendell found massive success with their 2023 production of Motherhouse, a world premiere by Tuckie White under the direction of Azar Kazemi, billed as a “trauma romp.” It’s a play steeped in loss and grief—themes, some argue, that repel audiences dealing with those elements in their daily lives. Yet the production extended three times, with many audience members coming back with friends and family, selling out the 47-seat theatre over and over again. While this may be a smaller space to fill in comparison to regional theatres with multiple venues, it’s a testament to audiences’ desire to witness not only new plays but ones with challenging themes.

Reflecting on the play’s success, director Kazemi and Mallen, who acted in the play, credit the long-standing 30-year history of the core ensemble, as well as a production process elongated due to pre-pandemic workshopping. What was also unique was that Rivendell contracted Kazemi before they selected a script. “Right off the bat, I appreciated that Tara was courting me and really wanted me to work at her theater, because of who I am as a whole of my identity,” Kazemi said.

People Over Possessions

Another common pressure point is the confluence of declining ticket sales and increases in costs of materials. As one op-ed we reviewed laid it out, “Increased costs create an income gap that must be covered by ticket prices, amplified by demand-based pricing; contributions; or reductions in the size of productions.” But forward-looking theatre companies are not only looking for increased funds to balance their budget—they are also actively finding ways to reduce material costs rather than the size of their productions.

One solution can be found in the historically largest line item of producing theatre: scenic design materials. The historic Free Street Theater (FST) learned this lesson early in their 50-plus-year career, as they literally took the show on the road and often performed with found items. Decreasing scenic costs not only helps a budget stay in the black; it also contributes to a green theatre movement in general.

Recently, FST made environmental justice a more explicit part of their mission. Producing artistic director Katrina Dion says that in her 10 years with the company (in a variety of roles), the work has always questioned how “theatre can continue to be a better server of larger social justice strategies.” Their youth-led production of Parched in 2019 was pivotal in exploring lead contamination in the water of South and West Side homes in Chicago, and inspired a trajectory for future shows with an eye on sustainability.

FST’s creative team leveled up their work in Wasted (both the 2020 online production and in person performances in 2021), with a design that specifically used recycled materials (including trash) as a part of the props and set. Then, with their 2023 production of We Have a Future/Tenemos un Futuro, the set, puppets, and props were made almost entirely of cardboard. Puppet maker Chio Cabrera even commits to never buying cardboard. Instead, she said, “I start my designs with what I have.” She also sources material from the team and neighbors. Frequent FST scenic designer Eleanor Kahn noted that storefront theatre budgets “don’t allow you to build and buy brand new every time.” So the way she works was through “repurposing, even if it wasn’t specifically for sustainability.”

Costume design both has a significant environmental impact and suffers from the negative impacts of being feminized labor, including low pay and lack of technical support. “Environmental impact also informs human impact,” said costume professional Elizabeth Wislar. “So if I’m trying to protect resources, I’m also protecting the resources of the people that I’m working with, I’m protecting my own personal abilities, time, labor, and skills.”

Wislar centers the land, the environmental impact of our industry, and ethics in her life and work. Years ago, she stopped buying materials for her builds and began “reallocat[ing] this money to people, to valuing their skills, to paying them for their time and their labor, and setting a rate of pay that corrects years of suppressed wage harm and feminized labor.” As Wislar says, the industry has “placed quantity over quality—quality of what we’re producing, but also over quality of life, quality of health, quality of labor support, quality of developing the skills.” She encourages the companies she designs for to continue to use this “people over possessions” model when they work with other designers.

Where Real Growth Is Happening

Over the years, the theatre industry has developed a constant drive for quantity: more productions, newer and bigger works, and larger buildings; and this is also what gets the attention of the press. Not only are these false goals—they also come at lasting expense to the field and to the people who make theatre. Industry leaders need to resist reverting to silos that disconnect them from solutions emerging in companies that look different than their own. Arts journalists and editors need to do this too: What if we highlighted innovation, sustainability, and equitable labor practices in theaters of all sizes the same way we cover building expansions, capital campaigns, and mass layoffs at large theatre institutions?

When news outlets focus only on the ups and downs of the largest—and predominantly white—theatre companies and their leadership, we not only lose the nuance and context about the problems we all face. We also miss the ability to learn more about what is working. SMU Data Arts and Chicago’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events released a report earlier this month titled “Navigating Recovery: Arts and Culture Financial and Operating Trends,” in which the researchers noted that while on average Chicago arts organizations reduced staff by 10 percent between 2019 and 2022, those averages were “driven by large organizations.” During the same time period, the report said, “small- and medium-budget organizations slightly increased their average staff sizes. BIPOC organizations and those whose mission focuses on the story and artistry of other specific populations grew their staff through the addition of both full-time and part-time employees.” In the same report, BIPOC organizations also saw an increase of 46 percent in individual giving between 2019 and 2022, as opposed to the industry average of no substantial change in individual donations.

Of course, these promising statistics don’t discount that the current crisis is the result of an industry built on an inequitable and unsustainable structure—a crisis that has been building up over years. The pandemic only sped up the inevitable for many companies. For others it offered space to build on foundations of equitable practices, or to chart new paths forward.

The period of shutdown “has led a lot of people to think, ‘What can we do differently?’” said Wislar. “What’s disappointing is that theatre, yes, is having a crisis moment. But it’s because [the industry] hasn’t engaged in doing anything differently.”

We work in one of the most collaborative and creative mediums. There’s no reason we can’t be innovative in our collaborations across the field, both in theory and in practice. Pooling together resources and knowledge is the most sure way of safeguarding the health of our industry and its people. In rehearsing and building the future of our field together—one that centers equity, a diversity of experience, and trust—we must continue to fiercely question our priorities, interrogate how we are living them. And we must tell, and share, different stories.

Yasmin Zacaria Mikhaiel (she/they) is a Chicago-based dramaturg, arts journalist, and adjunct professor. Learn more at yasminzacaria.com and follow them on Twitter @yasminzacaria aka dramaturgically it tracks.

Elsa Hiltner (she/her) is a Chicago-based costume designer, labor organizer, and co-founder of On Our Team. She works as associate director of programs at Lawyers for the Creative Arts and her views are her own. Learn more at elsahiltner.com.