To read a piece by Baron about adapting this play for Indian actors and audiences, go here.

In November of 1997, my first play, Visiting Mr. Green, opened in New York City. In it, a 29-year-old corporate guy almost hits an 86-year-old widower with his car on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and is sentenced to weekly visits with the old man. It starred Eli Wallach and David Alan Basche, and it ran for a year.

Since then, to my great surprise and delight, Visiting Mr. Green has always been playing somewhere, and often a lot of somewheres—in 45 states, 52 countries, a total of 600 productions so far.

I like to think that’s because it’s a good play. A lot happens, there are characters that you care about, and it has a satisfying ending. But most American plays that fit that description don’t travel as far or stick around this long.

The play’s longevity and reach may have something to do with my hands-on involvement, which I’m often told is unusual for playwrights. Since the beginning, I’ve offered creative support to most every production, large and small. I’ve gone over every translation line by line. And through my publishers, I’ve issued two major revisions to the play, including one just this year.

The first revision came in 2005. Phones play an important part in the story, and by then it had become very distracting for Ross Gardiner, a 29-year-old corporate guy in Manhattan, not to have a cell phone. He arrives at Mr. Green’s apartment one night, finds the old man motionless on the floor, and can’t call for help, because Mr. Green’s phone was disconnected years ago. Of course, Visiting Mr. Green could have stayed as it was and been presented as a period piece. The first Brazilian production did that, but the only way they indicated it was in the past, other than Ross not having a phone, was giving him a three-piece suit with the world’s widest lapels (see photo at right).

I proposed a revision to Dramatists Play Service, my publisher and licensor in North America, and they said yes. I took the opportunity to make other small changes. By 2005, I had seen productions of the play in many places, including Rome, Tokyo, Athens, Buenos Aires, Budapest, and Hendersonville, N.C.

A lot of the play is funny, so I could do what standup comedians do and fine-tune the comic material based on how it was playing. But I also decided to cut some lines that got huge laughs, in moments where the laugh took you out of the story. And for the dramatic parts, I saw so many great actors over-emote at the exact same places in the script that I realized the problem was me, not them. I toned down those moments. I tried out the 2005 revisions with Eli Wallach, who had become a good friend. He liked the changes (and believe me, he would have said so if he didn’t).

The 2023 update was just published by both Dramatists Play Service and Rowohlt, the German company that licenses Besuch bei Mr. Green. Since the 2005 revision, life has not changed very much for the reclusive Mr. Green. But for Ross, a young corporate guy struggling with his sexuality, there had to be updates.

Ross’s main issue is with his macho dad, who doesn’t want it known that his only son is gay. Ross isn’t open about his sexuality at work, but today he could be. So I cut the lines, “I go to work…and no one who has a job I want is gay. Or if they are, it’s some big secret.” I also cut the line where Ross complains about having to “laugh at stupid gay jokes” at the office. Not anymore, in today’s lawsuit-wary corporate culture.

When Ross comes out to Mr. Green, it takes a minute, but the old man seems to get it. Then the following week, when Ross announces that he got promoted, Mr. Green used to say, “So now you can afford to get married.” In 1997, and even 2005, audiences immediately knew that Mr. Green meant married to a woman. In 2023, when men in 34 countries can marry men, that line doesn’t quite work anymore.

The 2023 revision also addresses technological changes since 2005. At one point, Ross takes out his phone and Mr. Green demands to know who he’s calling. In the old version, Ross replied, “Information.” Unfortunately, there’s no 411 anymore. It’s a little thing, but it takes you out of the story.

Updating the text means updating all the translations too. When I wrote it, I never imagined this play being done outside of the U.S. But there was a scout for a German agent at the NYC reading that launched the play, and Visiting Mr. Green actually played in Aachen, Germany, before it opened in New York. Productions in the Netherlands and Brazil followed soon afterward.

Since I don’t speak German, Dutch, or Portuguese, I found bilingual people to read each version. In all three cases, they said the translation was good. They had a few questions, but just a few. When I reviewed those translations myself years later, I found many more things that were not quite right. Mr. Green tells the story of meeting his wife outside the bathroom his family shared with their neighbors 60 years ago. After setting the scene, he switches to the present tense: “I’m 25 years old. I’m just getting home from work. I run up the steps cause I gotta go. I get to the toilet, and wouldn’t you know it—someone is in there and someone else is waiting. The someone else who’s waiting, I never saw her before.” Mr. Green gets into the story, and before our eyes, this cranky 86-year-old turns into his frisky younger self. Part of it is the acting, but the immediacy of the present tense helps the actor get there.

But most translators, because Mr. Green is talking about something that happened 60 years ago, put the whole story in the past tense. “I was 25 years old. I was just getting home from work. I ran up the steps because I had to go,” etc. It’s not as good, and if I hadn’t been able to read the translations myself and then explain why I wrote it as I did, we would have lost a lovely moment in the play.

Over the years, online translation programs like Google Translate, Bing, DeepL, Systran, and Yandex have gotten better and better. Now I copy the translations into two or three of those programs and translate the translations back to English. You would never actually create a translation this way, but having used these programs on about 40 translations of my plays, I know the kind of mistakes they make, and I can use them to identify possible misunderstandings of what I wrote.

Lots of English words have multiple meanings, and some English words don’t have exact equivalents in other languages. When Ross is telling Mr. Green about his parents’ extreme reaction to discovering that he’s gay, he says, “I became completely self-conscious.” That simple phrase, “self-conscious,” has proven to be very difficult to translate. Sometimes it becomes “paranoid,” which is not quite right. Neither is “inhibited.” It makes me wonder if America invented self-consciousness.

My notes on the translation—including things like, “Mr. Green is not angry here. Please change the exclamation mark to a period”—give foreign productions a better understanding of my intentions for important dramatic and comedic moments in the play. They encourage a give and take that sometimes highlights cultural differences neither of us were aware of.

Unlike contracts for original screenplays and novels, it’s standard for a playwright to have approval of all translations. But when I send notes, foreign productions are always surprised, because apparently almost no one reads the translations of their plays. My overseas partners seem to appreciate that I do.

As Sophia Hsiao-fu Ho, who translated Visiting Mr. Green for Taiwan, wrote to say, “Thank you very much for your careful review of the translation.Your comments are very helpful for me to understand the script better. I am very surprised by how you correctly pointed out the subtleties of Chinese words and usages. That is so impressive. Do you know any Chinese?”

When I hear about an upcoming production of Visiting Mr. Green or one of my other plays through my website, my licensors, or Google Alerts, I reach out to the theatre. It doesn’t matter to me whether it’s a big professional organization or a community theatre. It’s a new audience for the play, and a new team of collaborators. I offer to answer any questions they may have, and I offer to send the director my expanded author’s note, which includes background on the story and what I think each character is going through before and after each visit. Having directed the play twice, I also share some production tips they may find helpful.

Aidas Giniotis, who directed the current Lithuanian production (Lankant poną Gryną), said, “We were very pleased that about 90 percent of your comments matched what we discovered while analyzing your play, which we have an honor to present in Panevezys.”

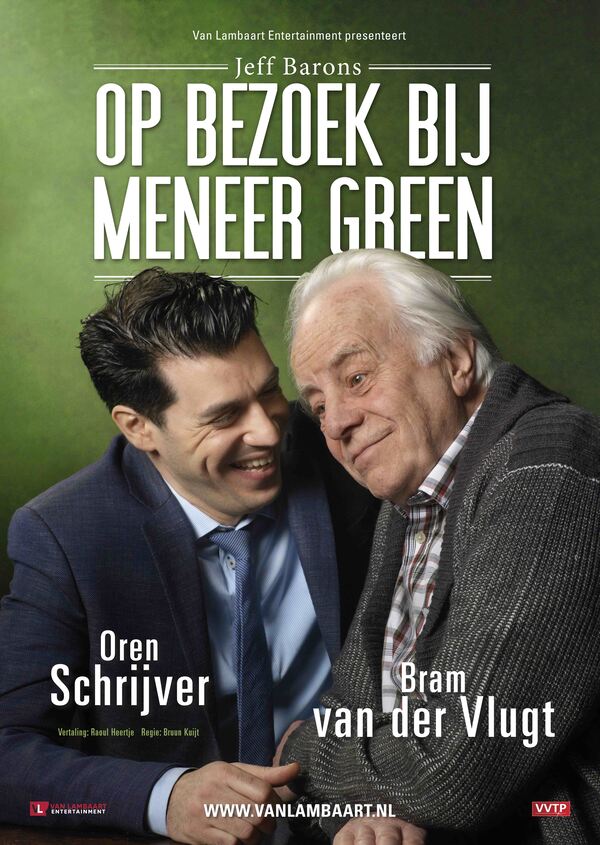

I sent the notes to Bruun Kuijt, the Dutch director of Op Bezoek bij Meneer Green. I wondered if it might be too much input. He wrote back, “Don’t worry about keeping me from discovering things myself. Rehearsing the play is during the day. In the evening, when I ‘m at home, I am reading your notes, where I most of the time find support from you. Support that I can use convincing the actors they have to listen to me…

I am often asked to weigh in on casting and marketing, and thanks to the new technology, I can “attend” rehearsals thousands of miles away and give notes to directors. I’ve also started doing Zoom talkbacks with audiences in other countries when I can’t be there in person.

Being in touch with theatres has been rewarding in so many ways. I have been invited to productions all over the world, and I frequently work again with the theatres and artists I got to know by reaching out and staying in touch. The world premieres of my plays Mother’s Day, When I Was Five (Cuando Tenía Cinco Años), the Mr. Green sequel (Retour Chez Mister Green), and What Goes Around were in Australia, Peru, France, and India, all involving people with whom I worked closely on their production of Visiting Mr. Green. The same is true for Mr. & Mrs. God, which will have its world premiere in French (Mr et Mme Dieu) at next year’s Avignon Festival.

In the last few years, reviews of Visiting Mr. Green around the world have been calling the play more timely than ever. That has more to do with world events than anything I’ve done to keep the play fresh. The resurgence of antisemitism and laws targeting LGBTQ people are certainly part of it. The pandemic made us all aware of the pain of isolation, which is central to the play.

But most interesting to me, in a world which has never felt so polarized, is that Ross and Mr. Green, people with opposing viewpoints, are forced to spend time together. They actually listen to each other, fight the fight they’ve each been avoiding for years, and ultimately find some common ground.

I can’t quite believe that the play has lasted this long, and I can’t say for sure that my efforts to stay involved and keep it updated are the reason. But as I get ready to leave for Athens in a few weeks for the opening of the second major Greek revival of Κάθε Πέμπτη κύριε ΓκρηνVi (Every Thursday, Mr. Green), using a brand new translation of the 2023 version of the play, I’m quite sure that working the way I do is its own reward.

Jeff Baron (he/him) is the author of the plays mentioned in this article as well as of the novels I Represent Sean Rosen and Sean Rosen Is Not for Sale, the award-winning film The Bruce Diet, and the one-act opera Song of Martina.