What does Shakespeare mean to us in the 21st century? Is he just another overly revered dead white male in an obsolete canon of so-called great books? Does he have anything to offer the American theatre of today as it grapples with issues of race and exclusion long evaded or ignored?

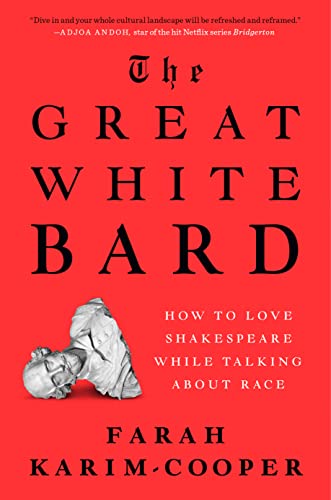

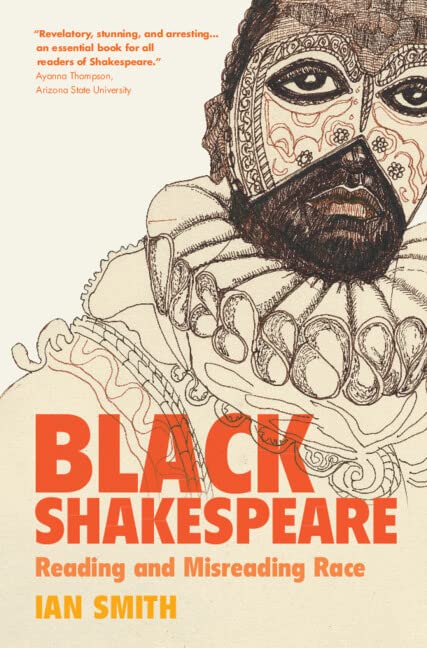

Absolutely he does, assert two provocative new books examining the racial attitudes expressed in the plays and in generations of gatekeeping white scholarship. Farah Karim-Cooper, education director at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London and author of several previous Shakespearean studies, takes a wide-ranging look at nearly a dozen texts, aiming to remove the playwright from his pedestal as The Great White Bard and immerse him in the hurly-burly of his time—and ours. Elizabethan particulars that raise contemporary issues are also the focus of Ian Smith, professor of humanities at Lafayette College and vice president of the Shakespeare Association of America, though he takes a narrower approach in Black Shakespeare, assessing Othello, The Merchant of Venice, and Hamlet (yes, Hamlet) in a dense scholarly text.

Both authors have encountered white Shakespearean specialists, and members of the general public, who bristle at analysis they believe inserts present-day concepts into the Elizabethan era or unfairly characterizes Shakespeare as racist. To the defensiveness epitomized by a Globe Theatre audience member who pleaded, “Please don’t ruin Romeo and Juliet by talking about race,” Karim-Cooper has an apt rejoinder: “Worry not, because the play can’t be ruined. It can be opened up, however, and questioned.” Romeo and Juliet was her “gateway drug” into Shakespeare, Karim-Cooper tells us. “A young girl in a patriarchal society is forced to marry someone she doesn’t know though she’s desperate to follow her own heart. This is the archetypal South Asian teenage experience.” Herself a young girl of Pakistani descent, Karim-Cooper writes that she felt “seen and heard” by Shakespeare, and her words here will strike a chord with anyone who has read Worlds Elsewhere, Andrew Dickinson’s entertaining book about the commonalities that people around the globe find in Shakespeare’s plays.

The problem, Karim-Cooper feels, is that Shakespeare is taught and discussed in ways that make him “unappealing, alien, and unrelatable” to many; the fault is not in the plays themselves, but in the process of glorification and sanitization over centuries that has positioned him as an abstract universal genius, and, by implication, an example of white cultural superiority. In Karim-Cooper’s quest to make Shakespeare “more relevant and accessible,” she offers close readings of Titus Andronicus, Antony and Cleopatra, Othello, The Merchant of Venice, and The Tempest that should dispel any concern that this approach means somehow dumbing him down.

Her consideration of Titus is particularly intriguing, since Aaron the Moor is among Shakespeare’s most villainous characters. Karim-Cooper does not scant the troubling equation of blackness and evil in Shakespeare’s metaphors, a centuries-old trope that persists in modern English, but she also notes the character’s “displays of Black pride, a self-love that no other character in the play exhibits.” Shakespeare employs racially charged language familiar to his audience to create a full-bodied character battling against white Romans who are no more moral than he, demonstrating that “barbarity is not exclusive to Rome’s outsiders.”

Karim-Cooper combines her evident love for Shakespeare with analysis that does not blink at, for example, the way his characterization of Cleopatra plays into stereotypes about women of color as sexually loose, or how fears and anxieties about miscegenation drive the action in Othello. Her point is that by acknowledging and examining the currents of race that run through many of Shakespeare’s plays, whether under the surface or in plain view, we do not diminish them but bring them into the 21st century as living works of art that speak to us in sometimes uncomfortable ways. “Shakespeare was not concerned with his audience’s comfort,” she declares, a statement as true 500 years ago as it is today.

Ian Smith gives Shakespeare even more credit in a fascinating exegesis of the first two scenes in Othello. Pointing to the striking contrast between the “black ram,” “thick lips,” and “devil” Moor described by white Venetians in Othello’s absence, and the confident, statesman-like general who enters to calmly explain with dignity the reasons for his marriage, Smith asserts, “Shakespeare mounts an assault on racist assumptions…forcing the English playgoers’ self-awareness of deeply held religious and racial bias.” It’s a stretch to impute this level of racial consciousness to a white Englishman born in 1564, no matter how multicultural Elizabeth society was. (Both Smith and Karim-Cooper spend a good deal of time reminding readers that the Age of Exploration brought many kinds of people to England, including enslaved Africans in the dark early days of the global trade in human flesh.) Nonetheless, Smith’s take on Othello offers much food for thought, as does his analysis of an enigmatic passage in The Merchant of Venice.

While negotiating his loan with Antonio, Shylock retells the biblical story in which clever Jacob tricks his shifty uncle into promising to give him all the lambs that were “streaked and pied”—e.g., not all white—then finagles (through highly improbable means) to ensure that the ewes in mating season produce mixed-color lambs. In a period when Jews were routinely disparaged as black, Smith posits, “Shylock’s Jacobean construction of blackness is coterminous with ingenuity, resilience, and tactical surety that resists cooptation.” I thought immediately of a moment in Arin Arbus’s 2022 production of Merchant when John Douglas Thompson as Shylock made a servile bow and flashed a disarming trickster’s grin at Antonio as he calculated his revenge. Smith’s book is clearly aimed at fellow scholars, but insights like these on Othello and Merchant could prove valuable to theatre practitioners preparing for production—and prepared to wade through some eye-glazingly academic prose.

Karim-Cooper’s style is more inclusive, and she considers performances as well as texts. She has sharp words for recent productions of The Tempest that presented Prospero as a benign colonizer and perpetuated stereotypes of the enslaved Caliban as completely monstrous, though she acknowledges such awkward facts as his attempted rape of Miranda. “Shakespeare was not one for making things easy for his audience,” she comments appreciatively. The Great White Bard rings with her conviction that an active, challenging engagement is the proper tribute to “the great and tumultuous world of Shakespeare’s plays.” She approvingly notes the decision by Kenny Leon, director of the Public’s marvelous all-Black production of Much Ado About Nothing in 2019, to cut Benedick’s wisecrack about Hero being “too brown for fair praise” and goes on to spotlight racist humor in such beloved comedies as As You Like It. We can’t ignore this discomfiting material, she argues; it alienates people of color and convinces more generations of schoolchildren that his plays are not for them. On the contrary, she affirms, “We all have the right to claim the Bard.”

Any critic who analyzes Shakespeare from a particular point of view—through the critical lens of race, in the case of these two stimulating books—risks being accused of reductive special pleading. But anyone who has seen more than one or two Shakespearean productions knows that his plays not only accommodate many different interpretations but thrive on them. Each new reading enriches our understanding, and none is the final word on his capacious art. By carefully explicating under-known or disregarded race-inflected language and attitudes in Shakespeare’s texts, The Great White Bard and Black Shakespeare take crucial steps forward in this never-finished project.

Wendy Smith (she/her) is the author of Real Life Drama: The Group Theatre and America, 1931-1940 and a frequent contributor to American Theatre.