As a West Coaster my entire adult life, I never had the chance to study with esteemed teacher and theatre critic Richard Gilman, who taught at the Yale School of Drama for 31 years. But I saw him once, at a Theatre Communications Group conference, in an appearance that truly inspired me. Erudite, witty, and winningly unpretentious, Gilman made me glad to be a theatre critic at a very polarized time, when we scribes were branded Enemy No. 1 by more than a few theatre artists.

After his appearance I introduced myself and thanked Gilman for his view that writing about theatre is a creative, meaningful contribution. He responded graciously. That brief encounter prompted me to read, and admire, his influential book The Making of Modern Drama and, especially, his Chekhov’s Plays: An Opening Into Eternity, both now out of print, but still valuable works that magnify and illuminate the lives and artistry of important dramatists.

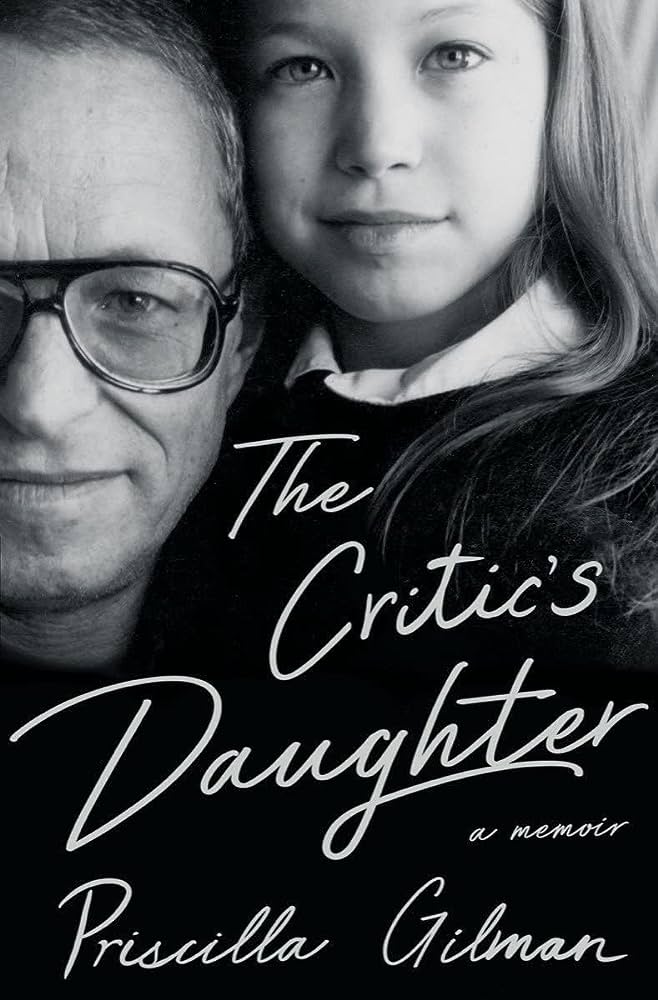

I mention all this because Priscilla Gilman’s intimate, thoughtful new book The Critic’s Daughter may strike those who knew or studied with her late father (he died in 2006) quite differently than it will those who knew only his writing, not the man himself. For me, this memoir read as a rare confluence of things—not so much a “Daddy Dearest” settling of scores, but a sincere attempt to untangle a father-daughter knot of love, hurt, and grief.

It begins as a reverie about the all but lost world of the close-knit, very privileged, Upper West Side literati milieu the author grew up in. (Her mother, Gilman’s second wife Lynn Nesbit, is a prominent literary agent whose clients have included Joan Didion, Gore Vidal, and Anne Rice, among others.) The book is also a proud account of Richard’s career as a multi-hyphenate intellectual, distinguished educator, and notable theatre and literature reviewer and essayist for (among other periodicals) Commonweal, Newsweek, The Nation, and, yes, American Theatre. Despite Richard’s many achievements (he also served as president of the activist organization PEN America for a time), his was a financially precarious, cobbled-together freelance career, as it remains for so many critics and artists today.

Priscilla’s memoir is studded with eloquent quotations from Richard’s writings. But the heart of it is her exploration of her enmeshed relationship with a devoted, demanding, and complicated father, and the impact of an acrimonious divorce on the children of an idealized parent. “I lost my father for the first time when I was 10 years old,” Priscilla writes in her preface. “In the months and years that followed, I lost him over and over, many times and in many different ways. This is my attempt to find him.”

She evokes a halcyon early childhood in the 1970s, when Richard was “a certain kind of New Yorker:” a politically liberal, charismatic public intellectual, and an exacting chronicler of a theatre scene bristling with experimentation and challenge. Raised Jewish in Brooklyn and later a Catholic convert (eventually a lapsed one), Richard was then an ebullient extrovert “with black clunky glasses and wild curly hair,” cutting a “dashing” figure on the New Haven campus and the Upper West Side.

The Gilmans lived in a now-uppercrust neighborhood back when a middle-class family could afford a spacious apartment at West 93rd Street and Central Park West, in an enclave bordered by parks, museums, bookstores, cafés. Though not ritzy, and not spared from the city’s grit and crime, it was the haunt of successful writers. Priscilla and her younger sister Claire attended private schools, and their parents socialized with a virtual Who’s Who of The New York Review of Books. Didion, “Uncle Bern” (Bernard Malamud), and other literary A-listers were frequent guests at their apartment and at their Connecticut country house.

Though comfortably ensconced at the time, as a critic Richard was an insurgent. He raged against “middle-brow” art and championed the burgeoning avant-garde as the “creation of radically new styles and patterns of consciousness.” His contention was that “theatre is only alive today when it is being brash, irreverent (or imaginatively reverent), disturbing, antic, dangerous, and even cruel…”

Richard was on the hunt for an “aliveness” that was inventive, transformational, unsettling. He exemplified, as Peter Brook wrote in The Empty Space, a “vital” critic “who has clearly formulated for himself what the theatre could be—and who is bold enough to throw this formula into jeopardy each time he participates in a theatrical event.” His standards were not often met, and he could be “extraordinarily” harsh in his reviews, writes his daughter, whose praise for his critical rigor is mixed with ambivalence: “He was famous for his ruthless, implacable judgments: no pity, no sympathy, no partiality at all.”

Richard helped to shape the craft and sensibilities of a Yale-schooled generation of theatre journalists via his seminars in criticism. Over beer and pretzels, employing unsparing analysis and scathing humor, his dissections of student work could be “brutal” and “devastating,” according to former student Dragan Klaic. As Klaic noted in a remembrance published in The Guardian, “He taught us to read with critical scrutiny. The sardonic deconstruction was sobering but effective. His standards were lofty; his judgements absolute.”

How harsh could he be in print? He quipped that directing actor Jason Robards Jr. would be like “pushing heavy furniture around the stage.” On Tennessee Williams’s late-career Broadway play The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore, he wrote, “Why, rather than be banal and hysterical and absurd, doesn’t he keep quiet?” He scoffed at “typical” American theatregoers, dissing fans of Thornton Wilder as “the reflective, the humanistic, the homespun, the quietly patriotic, the slightly disenchanted, the moderately iconoclastic, and all who crave ‘satisfying evenings in the theatre.’” Instead, Richard was an eloquent advocate for daring theatre he heartily believed in, whether from such historic innovators as Chekhov, Ibsen, or Brecht, or such contemporary mavericks as Peter Brook, Joseph Chaikin, Franz Kroetz, Sam Shepard.

For his daughter, however, all that “hypercritical” disdain for anything he deemed hackneyed or sentimental could be hard to live with. His uncompromising stance may well have seemed necessary, in a time when groundbreaking artists were often maligned outliers in mainstream American theatre. But his dismissal of popular culture made her fearful to confide some of her own youthful enthusiasms to him. Seeking Daddy’s approval was ingrained in their relationship early on.

In many other respects, Priscilla describes an adoring and fun-loving parent who handled most of the family’s childcare and bonded with his daughters over pro football and baseball games, Chinese takeout, Hollywood movies, even the musical Annie (despite its sentimentality). Away from the critical arena, he voiced “as much affection and respect” for Beatrix Potter stories as for Beckett’s Waiting for Godot.

Priscilla also observes, in hindsight, the casual alcoholism, creepy lechery, and blatant machismo among some of the male literary lions in her parents’ heady social circle. But through a child’s eyes, her youngest years seem in hindsight like a kind of Eden, in which attentive, playful Daddy was a shining star (he appeared on The Dick Cavett Show!), and so much more fun from her more aloof mother, the “flinty realist” of the family.

The couple seemed to balance one another well—until they didn’t, and their marriage ruptured. Priscilla was 10. She gives a searing account of their wrenching split, which felt like a betrayal to their daughters (as divorce often does to children). The disparity between Daddy’s piecemeal earnings and Mommy’s ample income meant that for years their daughters visited Richard in borrowed apartments and dingy rentals. They ached watching him grow bitter and depressed, irritable and lonely.

The child-parent roles reversed, and it became their job to comfort and buck him up, while not displeasing their mother (who was apparently glad to be rid of him). Priscilla’s childhood effectively ended with Freudian-nightmare revelations: From an explicit letter of Richard’s that he left open on his desk, she learned of his troubled “erotic nature” and masochistic sexual proclivities. Her mother later confided that she’d never loved him and complained about his adulteries and sexual inadequacy. This unwelcome knowledge “shattered” the “image of my father as an innocent, childlike being, honest and honorable, a family man above all else,” Priscilla writes. (More than 20 years before her own memoir, Richard addressed his troubled sexuality in a candid 1986 memoir, Faith, Sex, Mystery.)

Eventually a courtship and marriage with theatre scholar Yasuko Shiojiri rekindled Richard’s zest for life and work, and gave his daughters emotional (and geographical) breathing space when he went to live with her in Japan. But in the 1990s, Gilman’s health began to fail. He suffered a heart attack, developed lung cancer (he was a longtime smoker), and eventually lost his mobility and ability to speak before his death at 83.

His elder daughter felt acutely the irony in the long, grueling decline. “Becoming a professional patient radically altered my father’s being in the world,” Priscilla writes. “He was no longer the powerful one doing the assessing, the judging, the evaluating…He wasn’t used to being the passive one subject to others’ scrutiny and analysis.”

It’s meaningful that his demise isn’t the book’s final chapter; our parents are alive in us long after they pass. Priscilla goes on to address rearing her two sons, her own (more cooperative) divorce, and the reverberations of her father’s profound impact on her life. Her studies at Yale and burgeoning academic career had made him proud. But soul-searching prompted her to leave academia and chart a more personally rewarding course as an author and book reviewer, focused on parenting, autism, and education.

Near the close of The Critic’s Daughter, Priscilla comes full circle to explore how the film and theatre she and Gilman savored together in her youth—King Lear, West Side Story, The Wizard of Oz—mirrored aspects of their own relationship. She writes, “My father was always the Scarecrow to me: lithe and nimble, with ‘magic brains of a very superior sort,’ resourceful and plucky, and the one Dorothy will miss most of all.’” But most telling and poignant are her comments on Lear. Gilman called his daughters “my two Cordelias,” and often said Lear’s howl of anguish over Cordelia’s death in the play “wrenched him more than any other [scene] in literature.”

And in the end, she quotes one of her father’s ruminations on Chekhov’s art in a way that honors the playwright, the critic, and his daughter: “Lyricism doesn’t transform or redeem the weight of sorrow, it doesn’t even physically lighten it. What it does is place it, environ it, bring it into intimacy with the soul, which tested by grief, learns about itself.”

Misha Berson (she/her) is the former theatre critic of The Seattle Times and the author of several books on theatre, including Something’s Coming, Something Good: West Side Story and the American Imagination. She is currently a freelance writer and teacher, and a frequent contributor to American Theatre.