Read our accompanying interview with biographer Patti Hartigan here.

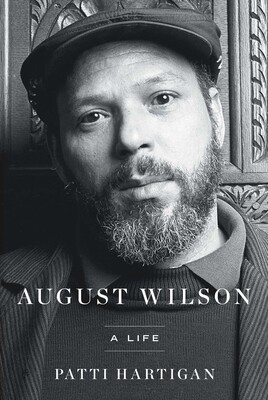

August Wilson, a two-time Pulitzer winner who ranks among America’s greatest playwrights, died in October 2005 at the age of 60. Though by the time of his death he had completed his American Century Cycle (a.k.a. the Century Cycle or the Pittsburgh Cycle), with one play for each decade of the 20th century, there lingered a sense that not only had he been taken from us too soon, but also that he had not yet reached the acme of his potential—that he still had great works left in him. The plays he left us with still resonate and are widely produced, and a few have been made into movies. In her riveting biography August Wilson: A Life, Patti Hartigan, an award-winning theatre critic and former arts reporter for the Boston Globe, gives the first full account of what Wilson achieved—and a sense of what he still might have done were his life not cut tragically short.

Hartigan’s book is the first to examine in depth how this high school dropout, raised by a single mother, went on to become a startlingly fresh, even essential voice in the theatre. Hartigan explores Wilson’s sprawling oeuvre and traces how his work integrated the complexities of his life, his poetic sensibility, and his commitment to authenticating Black experiences onstage.

Daisy Cutler, Wilson’s mother, and her siblings were part of the Great Migration, leaving Spear, N.C., for Pittsburgh in 1937. She gave birth to Frederick August Kittel Jr. in 1945. The father was a white German immigrant, a baker who did not play a role in the raising of the precocious young Freddy, who could read by the age of 4. Wilson’s mother earned his unconditional love and respect, and his work was one way he repaid the debt to her. He stated it best: ”I happen to think that the content of my mother’s life—her myths, her superstitions, her prayers, the contents of her pantry, the smell of her kitchen…are all worthy of art.”

Hartigan provides plenty of backstage anecdotes and private dramas, but keeps Wilson’s creative hardships, growth, and accomplishments front and center. She pulls from a deep reservoir, starting with his early days in Pittsburgh and the ways Wilson was shaped by, and responded to, his education, the racism of the time, an absent father, and feeling like an outsider in both the white and, to an extent, the Black world. Wilson came into his own when he discovered the blues and connected with a political sensibility that opened a door to poetry. At the same time he was influenced by the politics of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s, which informed his thinking all the way up to his historic 1996 TCG keynote address, “The Ground on Which I Stand.” Though Wilson did not graduate from high school, he spent whole days at the Carnegie library and later attributed his artistic education the four Bs: the blues, painter Romare Bearden, and writers Amiri Baraka and Jorge Luis Borges.

During his early days, Wilson had several poems published, and wrote a number of plays before the 10-drama cycle for which he is known, The Coldest Day of the Year, Recycle, and The Homecoming among them. He also had a musical produced during his formative years, Black Bart and the Sacred Hills. His activities as a director and playwright with Black Horizons Theatre in Pittsburgh prepared him for what was ahead.

Not long after she began writing the biography, Hartigan told The New York Times that she intended to write “a legacy biography, and a literary biography that shows how the artist can’t ever be separate from the art. The life is reflected in the art. I want it to show him as a human being and an artist.” She does show us that so well. Wilson, married in 1969 and a father by 1970, was living the existence of a starving artist with a baby daughter, and was devastated by the divorce from his first wife in 1973. The ups and downs of Wilson’s personal life, which included two subsequent marriages and another child, as well as a number of other friendships and romantic entanglements, encouraged Hartigan to dig deeper, and she has traced how Wilson’s personal experiences were channeled into his plays. For example, religion played a vital role in the dissolution of Wilson’s first marriage—his first wife was a Muslim, and though he respected her faith, he never converted—and Hartigan shows how traces of this conflict show up in at least three of Wilson’s plays (Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Fences, and Joe Turner’s Come and Gone).

Even amid his personal tumult, Wilson continued to move forward, and ultimately, after an invitation from his friend Claude Purdy (actor/director and cofounder of St. Paul’s Penumbra Theatre), he arrived and settled in Minneapolis in 1978. His writing and association with Penumbra Theatre were moving forward when another Pittsburgh friend, Rob Perry, sent him a brochure and advised him to submit a play to the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Conn. After several failed attempts, his play Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom was accepted and had a staged reading in 1982.

To everyone’s surprise, the Times’s Frank Rich not only violated the O’Neill’s no-review policy, he all but anointed Wilson right out of the gate. “Like most of the audience in the barn theatre in Waterford, I was electrified by the sound of this author’s voice,” Rich effused. “And surely I wasn’t the only one who left Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom with goose bumps brought on by the play’s unexpected esthetic resonance. Mr. Wilson is the kind of writer who fulfills the Conference’s goal to replenish our theatre’s future—yet, eerily enough, he works in the same poetic tradition as the man who inspired the O’Neill Center’s mission and who gave American theatre its past.” Two years after this nod, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom landed on Broadway, and the rest is history.

Over the next 12 years, Wilson kept me busy running to Broadway to see his plays: Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (1984), Fences (1987), Joe Turner’s Come and Gone (1988), The Piano Lesson (1990), Two Trains Running (1992), and Seven Guitars (1996). All six were directed by Lloyd Richards and two earned Pulitzer Prizes for Drama. To understand how this all came together is where Hartigan’s biography is required reading for anyone interested in American theatre history. She not only reveals how the surrogate father/son relationship between a Black director and a Black playwright enabled these two men to become such towering figures; she also takes us behind the stage and explores the drama behind the drama. Richards didn’t just nurture Wilson’s writing, he also set up a unique play development model for Wilson’s plays in which they would typically start with a workshop at the O’Neill (which Richards ran for nearly 30 years), then have several productions at various regional theatres, including Yale Rep (which Richards ran for 20 years), the Huntington, the Goodman, Seattle Rep, the Mark Taper Forum, and others, en route to Broadway. When this exemplary collaboration came to an end, chiefly due to a dispute over creative control and credit, many felt that while Wilson would not have become the dramatist he did without Richards’s tutelage and savvy, it was time for the son to move on from under the reign of his surrogate father. Hartigan does not answer all the questions raised by this intense and ultimately explosive partnership, but she provides clarity about the stakes of both their achievement and their parting.

The train kept moving, and Richards was replaced by Marion McClinton as Wilson’s director of choice. McClinton directed Wilson’s King Hedley II on Broadway (2001) and started work on Wilson’s next Broadway production; an illness intervened, and he was replaced by Kenny Leon, who directed Gem of the Ocean (2004) on Broadway.

Within a 20-year span, from 1984 to 2004, Wilson had gotten eight plays to Broadway (only Jitney didn’t make it there in his lifetime). Then in 2005 came the devastating news: He received a diagnosis of inoperable liver cancer and was given just five months to live. With this limitation, he raced to finish the last play of his 10-play cycle, Radio Golf, before his end. He did not live to see the eventual Broadway production of Radio Golf, directed by Kenny Leon in 2007, or the Broadway production of Jitney, directed by Ruben Santiago-Hudson in 2017.

In addition to the many interviews Hartigan did, she carefully examined letters and other materials to give us an accurate depiction of her subject, including his heavy smoking habit. I can personally attest to that—every time I encountered Wilson, he was smoking like crazy. But while there is so much in this biography, I would have liked to know even more about the creative collaborations that brought these plays to life. How exactly did Richards, as the director, improve the six plays he worked on? Similarly, I craved more specifics about Wilson gained from his dramaturgs and associates like Amy Saltz to Todd Kreidler. I feel there also could have been more about the contribution of and collaboration with the women who originated major roles in his work: There is a lot in the book about James Earl Jones’s influence on the writing of Fences, but I am willing to bet that Mary Alice, who played his long-suffering wife, also had some influence, or that Phylicia Rashad had more to say about Gem of the Ocean, in which she created the indelible role of Aunt Ester, or S. Epatha Merkerson, playing one of Wilson’s strongest female roles in The Piano Lesson. Finally, there could have been more citation of scholars who have written extensively about Wilson’s plays, including Alan Nadel, Harry Elam, and Sandra Shannon.

These are small quibbles. Hartigan’s writing style throughout is engaging, coherent, and dependable; she has given us a portrait of a gifted and flawed theatre artist in all his complexity. She has shown us how Wilson became the wonderful storyteller he was, and given us a measure of the significant difference he made in the cultural landscape. Above all, Hartigan affirms what Wilson was after, and achieved to a degree which still seems miraculous: a body of work that stands with the best of world literature, for the theatre or otherwise. Hartigan, with this first comprehensive biography, has honored Wilson in the way he deserves.

Nathaniel G. Nesmith (he/him) holds an MFA in playwriting and a Ph.D. in theatre from Columbia University.