Sitting down with Chicago director Georgette Verdin in early July had a bittersweet tinge to it. Interrobang Theatre Project, where Verdin served as managing artistic director, quietly announced earlier this year that they would officially be concluding their operations at the end of August. It’s another gutting blow for the Chicago storefront community, especially for a robust cohort of theatres that got their start in the city in the late aughts. AstonRep Theatre Company (2008), 16th Street Theater (2007), New Coordinates (2008), Sideshow Theatre (2008), and Interrobang (2010) have all now closed their doors.

“It was like this ecosystem of shared opportunities across everybody’s companies,” said Jackalope Theatre Company artistic director Kaiser Ahmed, whose company began producing in 2008. “It’s like an engine. It’s been really, really hard watching that get taken apart piece by piece.”

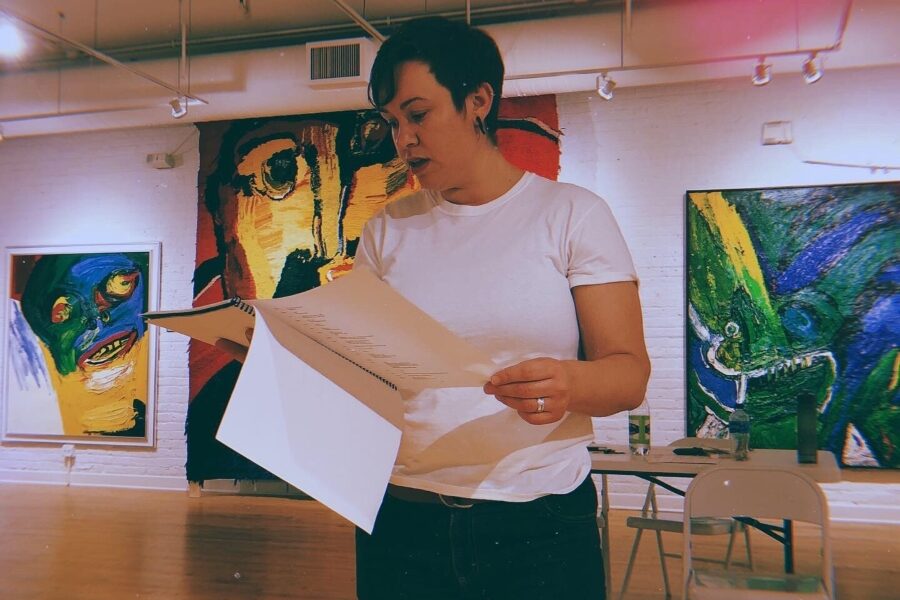

It is a storefront scene that has, for years, mixed artists just starting out with those who may have just completed a show at the Goodman the month before. And it’s a scene where an artistic leader like Verdin has been able to cut her teeth, make her mark, and do it all while working on projects that mean the most to her. So it feels almost counter-intuitive to both mourn the loss of those fertile scene stalwarts and celebrate the success the scene has led to for some of its artists. Verdin, for instance, was named “best local stage director ready for next big steps” by Kerry Reid and the Chicago Reader earlier this year. Last year, Verdin was the Goodman’s Michael Maggio directing fellow. She’s now an ensemble member at Rivendell Theatre Ensemble and an associate artistic director at Northlight Theatre. In talking to Verdin, one gets a sense of feuding feelings: excitement about a promising next chapter, and pain surrounding the rocky road that led to saying goodbye to the space that helped her get there.

“The universe has a way of putting you where you need to be,” Verdin said, “doing what you need to be doing.”

Growing up in New Orleans, Verdin said she was “an extreme introvert that can sometimes pose as an extrovert.” When she originally moved to Chicago, she thought she wanted to be an actor. But there was a level of vulnerability, of putting yourself out there and facing rejection, that Verdin didn’t want to give herself over to. So since she had also done some theatre education and worked with children as their director, she decided to get her Master’s in Directing from Roosevelt University.

“I thought that I was cheating the system by not being an actor and instead being a director,” Verdin said. “I could just hide behind the director’s table and tell everybody what to do and that would be great.” But she soon discovered that “as a director, you’re even more vulnerable,” because there’s no character to hide behind, Verdin explained. There’s also the unspoken weight of a show’s “vision” on your shoulders, not to mention the responsibility of creating a rehearsal environment that allows for fellow artists to thrive. She soon realized that she could be fine taking risks in controlled environments.

“When I started directing,” Verdin explained, “I had to get really comfortable with my work being seen and allowing people into my process, and not panicking about the perfectionism of only wanting to show people the finished product. That’s been a huge point of growth for me.”

One of the spaces that had allowed for her growth over the years was Interrobang. Since she started to work with the company in 2014, each of Interrobang’s typically three-show seasons has featured one Verdin-helmed production, including the U.S. premiere of Elinor Cook’s Out of Love and the regional premiere of Emily Schwend’s Utility. It was a space, Verdin said, where she was mostly left alone to hone her craft. She could program plays that felt important to her. As a queer Cuban American artist, she values works that uplift marginalized voices, and she gravitates toward plays that may seem small on the outside, but are emotionally expansive—plays that highlight the complex and messy moments that happen between people. Playing off the trope of “all sizzle, no steak,” Verdin said a friend has told her that she tends to be all steak, with just enough sizzle.

“Verdin doesn’t need to rely upon conceptual flourishes to make a space,” the Reader’s Reid wrote. “Instead, she builds the relationships between characters and text with careful attention to each small moment that reveals bigger truths about grief, joy, and everything in between, bringing audiences right up to the jagged edge of those emotional revelations.”

Verdin pointed to This Wide Night, a play by Chloë Moss, which Interrobang co-produced in 2021 with Shattered Globe Theatre. It was a quintessential Verdin production, centered on two women who are former cellmates trying to find their footing in their lives on the outside. Its intimate one-setting construction showcased what Jackalope’s Ahmed called an ability to “bend any space to tell the story the clearest way possible,” and was driven by acting and scene work. Verdin said she remembers reading the play for the first time a few years before she was able to produce it, and feeling excited about the potential of tackling a political topic through an intensely personal stories.

“I was like, I will be heartbroken if anybody else does this play in Chicago,” Verdin said.

It was in searching for a home for This Wide Night that Verdin sat down for drinks with Tara Mallen, artistic director and founding member of Rivendell. But Mallen turned the pitch meeting around: Mallen had been looking for a resident company to share Rivendell’s black box theatre. It can be tough, both Mallen and Verdin noted, for a company like Rivendell to be sure that itinerant companies will truly take care of the space they’re renting. In Interrobang and Verdin, Mallen said, Rivendell found kindred spirits.

“It was really a fantastic marriage for us at Rivendell,” Mallen said. “Not only was I getting to support an artist I cared deeply about, I really respected the whole community of artists that she worked with.”

It looked to be a beneficial partnership all the way around. Rivendell touts similar values to Verdin’s, dedicating their work to telling women’s stories and presenting theatre through a female lens. With similar artistic values, these two companies saw the chance to market to each other’s audiences, blending and growing in their partnership. In late 2022, the two companies co-produced the world premiere of Emily Schwend’s A Mile in the Dark, directed by Verdin. It looked to be the start of a future of Interrobang that saw the company branching more into world premieres, an aspect that has been more of a Rivendell specialty than Interrobang’s.

But as Verdin reflected back on these two co-productions, both with Equity-affiliated companies, she admitted that mounting both shows turned out to be heavy lifts. “That’s two companies putting their resources together,” Verdin said, “and we still struggled to the last minute to get all of the positions filled.”

The pandemic and all its fallout had done a number on Interrobang. It’s not that they hit a financial wall they couldn’t get past, like many theatres the pandemic has felled. Pre-pandemic, the company was reporting under $100,000 in expenses. No one had been working for Interrobang full time until just before the pandemic, when the company received a grant that allowed Verdin and Interrobang’s artistic producer to be put on W-2s. Just getting those two people on some sort of payroll, Verdin said, “felt like a huge accomplishment.

“But then,” Verdin continued, “this is a three-year grant with the understanding that we would be figuring out, okay, how do we keep this going? How do we, once this grant is over, replace that money to continue to build on our growth?”

The pandemic also saw the company lose board members to life circumstances: early retirement, moving away from the city. The ensemble began to drift as well, exploring lives in new cities, trying jobs in other industries, or pivoting attention to their families.

“There were only a few of us left,” said Verdin, who herself has a 2-year-old with her wife, Zoë. “It’s like, who are we going to leave this organization to? And in what shape are we going to leave it? We had all this momentum pre-COVID, and then it really took the wind out of our sails.”

Verdin said the company is closing with some money in the bank, which will be donated to other organizations in the city. But closing the company also left Verdin with mixed feelings about the state of Chicago storefront theatres. Pre-pandemic, the scene felt a bit saturated, with well over 200 theatres of varying sizes dotting the city. But as more and more close their doors, questions arise around what value is expected from those that are left. Are they meant to provide wages to pay people’s bills? And if so, are they expected to maintain the level of fundraising, marketing, and donor relations necessary to reach that goal? Or are they intended as an amateur space, a place for people to get their foot in the door and do work that potentially has less commercial appeal but may be more adventurous and more central to their artists’ interests?

“On the one hand, there are so many great conversations being had about what we owe people, how we should be treating people, and those are conversations that need to be had,” Verdin said. “It is complicated. I think figuring out what we value about the storefront space and what are our responsibilities is a conversation we need to be having.”

There are no easy answers, Verdin conceded. Just the hope that the theatres that remain will keep going and things will eventually turn around.

And so, again: It’s bittersweet. This artistic home, the company in which Verdin had grown into one of the hottest names in Chicago, a city not short on directors, is suddenly gone. Meanwhile Verdin is getting ready for a busy second half of 2023: This week saw previews open for her production of The Writer by Ella Hickson, at Steep Theatre; October brings the opening of Lucille Fletcher’s Night Watch at Raven Theatre, directed by Verdin; and then her Northlight directorial debut comes during this holiday season, with Jeffrey Hatcher’s adaptation of Dial M for Murder.

“It’s not the way I imagined it all going down,” Verdin said, “but I’m really proud of what we accomplished. I’m proud that we are making the decision for ourselves. This feels like an organic, natural flow to the company.”

Jerald Raymond Pierce (he/him) is the Chicago Editor for American Theatre. jpierce@tcg.org