Let’s think for a moment about genre fandom. What’s the mark of a sophisticated cineaste? Often, knowledge of world filmmakers. Serious fiction fans are as familiar with Orhan Pamuk as they are with Hilary Mantel. Significant U.S. galleries and museums often exhibit non-U.S. artists. If we can imagine that a fair number of average U.S. arts consumers have heard of the Cannes film festival, why is it that most leaders of major U.S. theatres have never heard of the Theatertreffen?

Indeed, the number of contemporary plays in translation produced in the U.S. is vanishingly small. In the quarter century that American Theatre has been publishing most-produced-play lists, only one contemporary non-English playwright (Yasmina Reza) made the cut, among the 125-odd playwrights represented. This gap isn’t for lack of sophisticated material to engage! Theatre scenes in scores of countries around the world are every bit as sophisticated as ours in the U.S. (and in many cases far better funded). So why are U.S. theatres generally so unconnected to what’s going on in the non-English-speaking theatre world?

There are a hardy handful of U.S. theatre companies that do create globally engaged work, including the one I founded and lead, the Cherry Arts in Ithaca, N.Y. For this article I decided to reach out to a number of others, because, even after seven years of producing international plays, I have realized that most of us don’t know much about each other. So I’ve set out not only to provide American Theatre readers with an overview of this vibrant niche in our industry, but to help bring this collection of companies into contact with one another.

I spoke to about a dozen companies around the country who are creating a broad range of work. “(Apologies to those I inevitably missed—and a shout-out to the vital group of companies that create work out of U.S.-based immigrant and/or racialized communities. These run the gamut from Noor and NAATCO to Repertorio Español and Gala Hispanic Theatre, and many others, and as a group they deserve their own article.)

On this virtual tour, the longest-standing producing company I spoke with is also the company which has perhaps most profoundly embraced the possibilities offered by international collaboration: Philadelphia’s Wilma Theater. The company was founded in 1973 and fully assumed its international focus when artistic directors Blanka and Jiri Zizka, two immigrants from Czechoslovakia, took its reins in 1979. In 2011, Blanka founded the Hothouse Company, the Wilma’s version of a European-style acting company, which has since trained and collaborated with dozens of artists from around the globe. Since Blanka’s retirement in 2020, the company has had a shared leadership model, with a small cohort of company artists trading off leadership duties.

Turning to D.C., we find both one of the newest companies and one of the most long-standing. ExPats Theatre was founded in 2019 by German-born actress Karin Rosnizeck, and despite the pandemic’s arrival on the heels of their founding, they’ve produced well-received plays by Romanian, Serbian, Czech, and Austrian writers. Meanwhile D.C.’s Scena was founded in 1987 by artistic director Robert McNamara and managing director Amy Schmidt, and in that time has created dozens of touring as well as D.C.-based productions of international texts.

In Chicago, another long-lifer is Trap Door Theatre, founded in 1994 by artistic director Beata Pilch. The Eastern European-inflected company not only produces an annual storefront season of 5-6 productions, almost all scripts in translation, but also maintains a sizable touring company performing throughout France, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and elsewhere. Also based in Chicago is the International Voices Project, led by founder Patrizia Acerra. IVP works from a different model than the other producing companies I spoke with: Since 2003, they’ve primarily been known for an annual festival of readings, presenting a dozen or so plays from around the world. IVP also regularly co-produces full stagings of particularly successful texts with other Chicago institutions, including Trap Door.

Looking to NYC: Since 2000, as founding producer Kate Loewald put it, the Off-Broadway Play Company has been “producing a global program of work that includes American work, so that our American theatre is in conversation with theatre around the world.” A considerable number of plays PlayCo commissioned or premiered in English have been published and produced around the U.S. On the scrappy Off-Off-Broadway end of the NYC spectrum, Voyage Theater Company has been in business for a decade, under the guidance of artistic director Wayne Maugans, producing plays in translation alongside U.S. plays that focus on immigrant communities.

In L.A., City Garage Theatre ties D.C.’s Scena for longevity. Frédérique Michel, a French former actress and the company’s artistic director, co-founded the company in 1987 with executive director Charles Duncombe. City Garage’s method reminds me more or less of Scena’s and Trap Door’s: a strong, singular directorial voice (Michel directs all the productions and Duncombe designs them) and an assertively non-naturalistic style, which makes use of the directorial freedom often offered by texts in translation.

The final cities represented in my survey are St. Louis, where Polish-trained director and translator Philip Boehm founded Upstream Theater in St. Louis in 2004, and has since produced dozens of global scripts, many in translation, alongside the occasional U.S.-written play, and Ithaca, N.Y., where Cherry Arts began producing in 2014, balancing translated plays with new works based in Ithaca’s communities and histories, under the watchwords “radically global, radically local.” Cherry has produced over a dozen plays in translation from more than 10 different countries, with several going on to publication and/or other productions.

As you can imagine, my conversations revealed wide contrasts as well as strong common themes. One clear takeaway: the structural differences between the Anglo theatre ecosystem and many others. Beata Pilch of Trap Door recalled that as a teenager, she “fell in love with theatre in Poland. I had always loved theatre in the U.S., but this just couldn’t compare. I couldn’t understand why it was so different.”

As in all big systems, many of us who make work in the Anglo theatre ecology may not even be aware of how specific and unusual our system is from a global perspective. As Erwin Maas, the Dutch-born former programming director of NYC’s Origin Theatre explained, “The English-speaking world is very playwright-driven, it’s very word-driven, it’s very textual.” In the U.S. system, the script is the central object of theatremaking. Scripts are developed and finalized in a new-play development creative process, and after the world premiere, the most producible plays travel to theatre companies across the English-language world in different productions, created through similar rehearsal processes. By contrast, Maas says, “Outside of the English-speaking world, there is not necessarily this enormous reverence for the playwright. There is much more devised work happening.”

At the Wilma, co-artistic director Yury Urnov said that “each production has its leading element.” For the upcoming play, Mama and the Full Scale Invasion, the focus is the text by Ukrainian writer Sasha Denisova. But when Russian director Dmitry Krymov directed The Cherry Orchard there last fall, the focus was design, while a work with Csaba Horváth, the Hungarian director and choreographer, put its emphasis on the body. “Theatre language includes the verbal language of the play,” he said, “and sometimes it’s even a leading one, but not necessarily.” This squares with what a German theatre colleague once told me: that in much of Europe, when artistic directors have a new-work slot in a season, they don’t select a play but rather a director, whom they then ask whether they want to work with an existing script or start from scratch. The author of these works is often the director as much as the writer.

Naturally, works that are less text-based don’t spread by circulating the script so much as by touring the entire production. And a fairly large amount of touring international theatre work is presented rather than originally produced in the U.S. A lot of these presentations happen on a large scale in big cities, via organizations like BAM, St. Ann’s, The Armory, WorldStage at Chicago Shakespeare, On the Boards, the Walker, and so on.

But without diminishing the importance of the vital work of these presenting institutions, producing theatre companies who engage international voices are able to do something quite different, and perhaps more profound. As Loewald of PlayCo put it, “It’s important for us to draw the distinction between those festivals, which are great, and what we do, which is really trying to bring American artists and audiences in contact with artists from other parts of the world in a much more direct way. So we’re sort of cooking something up together.”

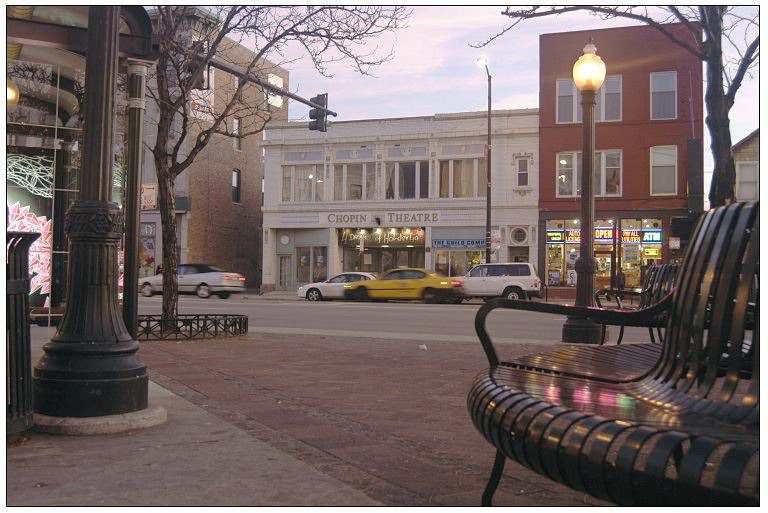

I do want to pause to highlight the work of two particular presenting companies here, both of whose methods of presenting, with their intimate scale and close developmental relationships among artists, give their work the feeling of “cooking something up together” rather than hosting a tour. Since 1990, Chicago’s Chopin Theatre, co-administered by founder Zygmunt “Ziggy” Dyrkacz and his wife, Lela Headd Dyrkacz, has housed a dizzying number of international performers and productions, cheek by jowl with a vast number of smaller Chicago theatres whose practices often engage international texts and/or techniques. And, of course, NYC’s LaMama E.T.C., under the decade-long leadership of Mia Yoo, is the iconic grandmama of the U.S. international and experimental theatremaking scene, having begun its practice of global collaboration not long after its 1961 founding by “Mama” Ellen Stewart.

But back to producing: If other theatre scenes center the director over the playwright, wouldn’t it be more truly international to import directors rather than scripts? (As noted above, this is the sort of thing the Wilma often does.) Most U.S. theatres, though, are not ready for that, either structurally, or, honestly, aesthetically. Our system is built around selecting, then rehearsing, scripts.

So what kind of scripts get written in spaces that decenter the playwright? In my conversations for this article, the feeling emerged strongly that playwriting that is unburdened of final authorship can be freer, less prescriptive, and designed to inspire creativity in a director and production team, rather than being tasked with providing, effectively, a book of instructions for making the play. In the opinion of Rosnizeck, of D.C.’s ExPats, “European plays are a lot more bold, a lot more using the medium.” Philip Boehm of Upstream elaborated: “What gets produced here is pretty much standard American realism. Of course, in European theatres, styles and forms are all over the place. So many of the plays we have introduced to the St. Louis audience have also brought a variety of genres.” Said PlayCo’s Loewald, “Part of what we want to do is present different ways of writing and making theatre—saying, This is theatre, and this is theatre, and this is theatre—so it’s not all, you know, well-made plays.”

Make no mistake, U.S. productions of these kinds of scripts may be a better fit on the second stage of a big institution than the big one, or in that community’s “alt” theatre company. But they can be an exciting fit there indeed.

Others noted that producing this work doesn’t only expand artistic perspectives but philosophical ones as well. Chopin’s Zygmunt and Lela spoke, characteristically, as a tag team. “If you invite people from a certain country, they present different aesthetics, different fields of interest, different kinds of sexuality, different artistic visions,” Ziggy began. “And then,” Lela chimed in, “you begin to have some context by which you can measure your own life, when you can see the tapestry of what’s out there.”

Boehm notes that works from other countries “perhaps give audiences, not only a window into another culture, but also some chance to reflect on their place in a larger world.”

Similarly, Lindsay Smiling, co-artistic director at the Wilma, noted of their global collaborations, “You start to see how these different approaches are pointing to the same thing. Where are we going with the human experience, and how do these different approaches get to it?” Added Acerra, of the IVP, “People who are curious about a culture may find a way into a conversation about it through theatre, or learn something new—you know, fresh snow. It’s a great image I have: walking with people on fresh snow, a place they’ve never been before. It’s really exciting.”

I found these creators to be often as passionate about their audiences as about the work. Said Duncombe of City Garage, “I think the people that we speak to are people that are looking for alternatives to mainstream entertainment. People who are concerned about ideas, about the state of the world, and who appreciate a different perspective.” Acerra swore that IVP’s readings have “the best audiences in Chicago. I know I’m a little biased, but it’s this wonderful combination of people interested in theatre and culture and politics and language. And so the conversation is rich, and you see people you never see in the theatre.”

As exciting as these audiences are to the leaders of these (mostly small) theatres, how big are these audiences? An artistic director of a large organization that relies significantly on box-office revenue could be forgiven for wondering. As rarefied as some of these international companies’ audiences may seem, many also reported an aspect of audience-building that took me by surprise. Unlike the Cherry’s small-town Ithaca scene, almost every company I spoke to was based in a city with sizable immigrant communities, and connecting international productions with these communities has been a big part of their box-office success. Upstream reported early hits with productions that spoke to St. Louis’s significant Bosnian and Polish communities.

Rosnizeck had a similar experience with one of ExPats’ first productions. “When I did Einstein’s Wife,” she said, “I told the Serbian embassy, ‘Hey, do you wanna send people and give them discounts?’ And all of a sudden I had all these Serbian names on the list, and it was full!”

Of Trap Door’s first production, Beata Pilch recalled, “We had this great opening, and great reviews, but the big splash was in the Polish community. If we didn’t have the Polish people, we wouldn’t have had an audience.” Maugans said of Voyage’s first production a decade ago, “We did it in Russian and English with a bilingual cast on alternating performances…and the Russian audiences especially came out in droves to see it. We would be sold out on the nights when they were performing in Russian and have five people in the house when we were performing in English.” As someone who has had the experience with new companies producing Off-Off-Broadway in which just five audience members come every night, Voyage’s maiden voyage sounds like a pretty good outcome to me.

It is true that a large segment of immigrant-community audiences may not return to see shows from countries other than their own (Ziggy Dyrkacz bemoans the “tribal mentality” that sometimes produces these effects at the Chopin). But if even one in 10 of these audience members do return, over the course of years a theatre will have built an audience of profound diversity, with seams extending deep into the many global communities that increasingly make up U.S. cities.

This kind of audience development may be becoming less and less optional. LaMama’s Yoo noted that even communities far from coastal big cites are becoming more diverse, anticipating “the demographic shift in this country that’s going to happen in a few decades. So how are we all, as a national community, going to grapple with that? We’re feeling growing pains, definitely, of what that’s going to look like, and how we’re going to navigate our differences—but also, where are we coming together?”

But even if every alt theatre and LORT second stage in the U.S. were to commit to producing an international play next season, where would they find the plays? Needless to say, many plays that are wonderful in their source communities don’t travel well. So where is the pipeline? When I asked the theatre leaders in this article where they found their plays, they explained that being multilingual, and spending long years building international networks, was key. That has been my experience as well. This may not be practical for every company who might be interested in doing more of this work. But a few immediate options present themselves.

The websites of the theatre companies I talk with here all list performance histories, but this is hardly a centralized resource. The New Play Exchange of the National New Play Network has been an exciting addition to the U.S. theatre-writing landscape, but its structure has made it unfortunately challenging to catalog non-English-originated works. The news on this front may be good: NPX project director Gwydion Suilebhan told me that this summer the database is aiming to launch a long-awaited update, allowing fields for “translator” and “original language” alongside a number of other improvements.

Available right now is the online journal of theatrical translation The Mercurian, edited by UNC professor and theatre translator Adam Versényi. The Mercurian is fundamentally a scholarly journal, and while some of the translations it publishes are suitable for production (the Cherry produced a beautiful Salvadoran play we found in The Mercurian’s digital pages), many have a more scholarly or historical focus, and the archive may take some digging through. Chicago’s International Voices Project curates 8 to 10 contemporary, producible plays a year for their reading series, but until now there hasn’t been a mechanism for making these works centrally available for perusal. Happily, as this article is coming together, it seems as though The Mercurian and IVP may come together as well, for one or more special issues that could make some of IVP’s rich archive easily available for readers.

Another potential source of international scripts is Eurodram, a vast pan-European network of new-play exchange. (Full disclosure: I co-chair the Eurodram English-Language Committee, a volunteer position.) Every two years, plays in translation are submitted to each national language committee, who each select three plays in translation to recommend for production in their own theatre world. Eurodram is a terrific source of European plays in English, but overstretched resources have held back the network’s effectiveness at getting the word out and making the selected plays available to a wide Anglosphere community. The network feels ripe for potential collaborations and improvements, some of which the Paris-based leadership are considering. (For anyone seeking an inside view, Eurodram’s English Language committee—eurodramenglish.wordpress.com—is always looking for volunteer members interested in reading excellent new plays from across Europe.)

Every bit as much as Europe, Latin America produces an extraordinary quantity of potent theatre writing that resonates in the U.S. On this front, Out of the Wings is a London-based “research and practice community” for theatrical translation from Spanish and Portuguese, encompassing contemporary and historical writing from both Latin American and Europe. OOTW produces an annual curated festival of readings (ootwfestival.com), as well as, for community members, informal weekly table reads of new translations. OOTW’s founding project was to create a large database of English translations of Luso-Hispanic theatre writing, accessible on their website. The challenge here for the contemporary producer, as with The Mercurian, might be simply navigating the large number of texts, many of which were translated for scholarly purposes.

Alas, I’m not able to offer a centralized lead on scripts from Asia, though NYC’s PlayCo, for example, has had success with exciting new theatre writing from Japan. And I’m painfully aware of the relative whiteness and global North identification of many of the plays that come to international producing theatres. Here I wonder if another phenomenon is afoot. The U.S. theatre is rooted in profoundly Western European traditions, and many global majority cultures create performance in ways profoundly different from the U.S. Looking to these countries to provide playscripts that are production ready for the U.S. theatre system may be a borderline colonial impulse. The most responsible way for U.S. institutions to engage and present work from many global majority cultures may be through touring or longer-term residencies and exchanges.

As in every part of the theatre world, the list of U.S./global companies is sadly shorter post-pandemic. In NYC, both the Lark, longtime home to the US-Mexico Playwrights’ Exchange and HotINK international play festival, as well as the Public’s Under The Radar festival, which presented a lot of global work, recently shut down. Chicago’s Sideshow closed in March after 15 years of producing plays by U.S. and global writers. Albuquerque’s Tricklock Theatre, which produced an annual global Revolutions Festival, closed in 2020. Other theatres may shift focus as new artistic leadership takes over: in NYC, the Origin Theatre is transitioning from a pan-European outlook to the Irish focus that was their founding mission. NYC’s Rattlestick began to explore an international outlook under artistic director Daniella Topol and managing director Yue Liu, and new leader Will Davis, who recently oversaw the theatre’s Global Forms festival, has committed to continuing this thread of the company’s work.

The challenges are real. But, to put it mildly, this is not a moment when traditional theatre programming feels like a surefire recipe for success either. Jim Nicola ran New York Theatre Workshop for 34 years, always striking a balance and finding the overlap between adventurous and crowd-pleasing work—often with a connection to international creation. In an email he told me: “I believe that we are in a crisis. There will be no theatre to speak of if we don’t start considering other ways, aesthetics, structures. Different perspectives on art-making keep the public discourse deeper and more probing. Artists who make work in different cultural contexts can only help us all in the search for a better world.”

But in a climate of anxiety and risk-aversion, what is the likelihood of entrenched institutions crossing new artistic borders? “I’m always an optimist,” said PlayCo’s Loewald. “I think there are growing audiences for global works now. I also think that younger people, if they’re not already demanding it, they’re at least more open to it. Because the world is on their phone, and this is how they experience the world.” Acerra, of Chicago’s IVP, is also excited: “I feel like the old ways have fallen away, and the old assumptions are gone, and there’s a space where it feels like there’s literally nothing. Which means the potential for everything!”

LaMama’s Yoo sees the big picture, reaching all the way back to the lessons of Ellen Stewart’s first visits to Europe in the 1960s. “She realized that that cross-cultural exchange, or confrontation with something that wasn’t yourself, ultimately impacted the artists that she was working with in ways that she didn’t even imagine,” said Yoo of her predecessor. “And how I see it at this point, after being fortunate enough to have these incredible global experiences with her, is that when you do come in contact with something that is not like yourself, you start thinking about who you are, you engage with the world, and start taking in new perspectives, and starting to understand, what is this idea of humanity? And what do we share? And what are the differences? But you also kind of get a deeper understanding of who you are, right? And I think as an artist that’s incredibly invaluable—maybe essential.”

Samuel Buggeln (he/him) is a Canadian theatre director and translator based in Ithaca, N.Y. He is the artistic director of the Cherry Arts, a multi-arts hub programming performance, art gallery, and studio spaces. Cherry’s central creative focus is producing theatre that is radically local, radically global, and formally innovative.