The story of housing in Detroit, especially for Black and brown people, is a complex tale, woven over generations from the strands of redlining, restrictive covenants, predatory lending, gentrification, housing projects, and unethical real estate practices in the post-foreclosure crisis. Now housing activists, community organizers, and artists are combining media to unravel this complicated tapestry and capture the attention of a new generation.

On June 30 at 7 p.m. and July 1 at 2 p.m., the Detroit-based ensemble theatre A Host of People will present Dot’s Home Live, a devised theatrical event adapted from the video game “Dot’s Home,” touching on themes of racial justice, housing policy, and time travel. It’s a collaboration between A Host of People and Detroit Action, an affiliate of PowerSwitch Action, a national network of housing organizations. The show will take place at Andy Arts, a community arts center on 3000 Fenkell Street in Northwest Detroit.

Christina Rosales, a housing and land justice director for PowerSwitch Action, originally co-created “Dot’s Home” in 2021 as a way to help build solidarity and community. The game starts in present-day Detroit, with a young Black woman named Dot living with her grandmother, Mavis, in their family home. They immediately confront a predatory speculator who is buying up homes in the neighborhood to flip them for a profit. As her grandmother mulls selling the home, Dot steps through a door that takes her on a journey through time to witness her family’s history with the house, from the time her grandparents first arrived from the South to her parents deciding whether to stay or leave Detroit, to her sister becoming a real estate agent and making decisions about the neighborhood. At every historical point, the player makes decisions for Dot’s family that have repercussions in the present day. The stories of the game were based on real incidents in the lives of the developers on the team, many of whom had connections to Detroit.

“I came into this work as a housing organizer,” said Rosales, “and the whole thing behind creating the game is to reach an audience we don’t normally reach and then to have them grapple with these big questions about what it means to have these huge disparities and wealth and home and opportunity.”

While the game won awards and educated its players about how exclusionary housing polices have historically kept people of color from achieving home ownership and building family wealth, Rosales acknowledged that video games have limited utility as an organizing tool, since people typically grapple with them individually rather than in a community setting.

“That’s hard when you’re trying to build solidarity as a collective toward this vision you have,” Rosales said, adding that she and their team toyed with how to bring the game to a group setting and use it more effectively in organizing. “What seemed to make the most sense was theatre—you go into a theatre as individuals, but you experience something as a collective.”

Their team approached A Host of People in December 2022 about turning the video game into a theatre piece. Paige Wood, the game’s supervising director and a Detroit artist, was familiar with the theatre ensemble and their work, and connected the two organizations. Sherrine Azab, co-director of A Host of People, got excited about the project as soon as she played the game. She said the project has moved quickly since then, as the troupe has written the script, tried it out in front of a test audience, and revised it further.

“What’s really great about the video game is that the story really lends itself to coming to life,” Azab said. “The characters are really fleshed out. They have a lot of backstory already. The world builders have a lot of information that has been given to us about who these people are.”

A team of people, including Rosales, Wood, and her co-director Toni Cunningham, have collaborated on adapting the game into a theatrical script. The process has involved many partnerships with community organizations, who have provided feedback about how the show will be presented and how it can be used to take action while still being a high-quality arts experience. It provides a model, Azab said, for how grassroots organizations can use arts and culture to spread their message and further their work.

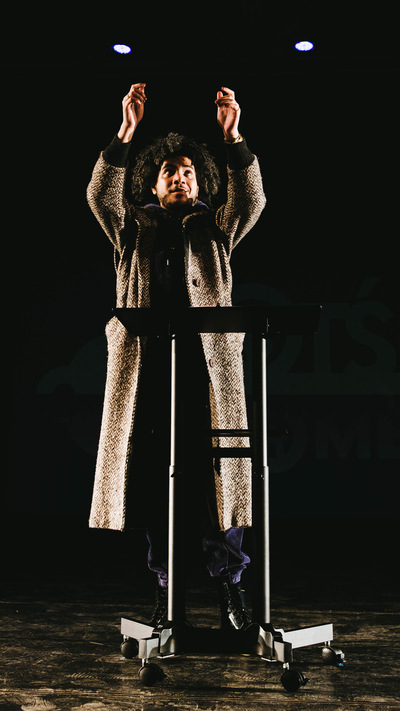

One major change from the video game: the creation of a host character named 4D, who guides the audience through the choices that change the direction the script takes. Chris Jakob plays 4D, and will act as an intermediary between the audience and the actors. As Dot takes her journey, there are moments that 4D will pop in to provide historical context and ask the audiences what decisions he wants to have her make.

“4D is definitely the video game element,” Jakob said. “Everything else is essentially a play in so many ways, but he adds the twist. He’s called 4D because he really does break through another dimension. We’ll have so many elements from the video game and so many visual cues for decisions that are very much like the game.”

At the show’s end, the audience will witness how their choices have affected the future of Dot’s family, with the cast prepared to present different endings based on those choices. In April, A Host of People did a 25-minute test production of the prologue and first “chapter” of the game to test their proof of concept. It was also a chance to test some of their projection designs, and whether they supported the audience choices. The test audience comprised members of Detroit Action.

“Their buy-in to the project was instantaneous,” Azab recalled. “Everything in regards to the audience interaction completely worked, and we had an amazing discussion afterward about how much more interaction they actually wanted.” The choices presented in the game “are quite hard,” she added, inviting deep emotional engagement with the character, but game format also means “you’re having an amazing collective experience with the people around you that feels very lively and participatory.”

Rosales had felt it was important to have community partners contribute to the early stage of the development to make sure Dot’s Home Live will be an effective organizing tool. But she found that the feedback focused a lot on improving the game aspect.

“They had a lot to say,” Rosales said of the Detroit Action test audience. “They were overwhelmingly positive about the experience, and then they said, ‘We need more participation.’”

They also helped identify areas of the script that needed more clarity, such as concepts related to redlining and contract for deed, a predatory practice that has often been used to drain home equity from communities of color.

Ultimately, Rosales said she wants Dot’s Home Live to speak to artists and audiences about their critical roles in making a better society.

“I want artists to know that their voice and vision is so important to movement work,” Rosales said. The physical reality theatre, she added, gives audiences “more of a chance of envisioning and practicing a multiracial, feminist democracy. The sign of a healthy democracy and civic life is that there’s impactful theatre pieces in the world and that they are accessible to all kinds of people, including the folks we’re including in this whole collaboration.”

Azab concurred: The theatrical form, she said, can energize people in a visceral manner, drawing everyone on a journey together to witness how housing policies have affected real families in real time. She marveled at “the collective experience of being able to have these conversations with others and to be able to share not just stories that people are experiencing, but to be able to generate coalition building.”

Bridgette M. Redman (she/her) writes about theatre and the arts for publications around the country. Her work has recently appeared in Encore Monthly, OnStage blog, and the Chicago Reader. She’s been a theatre critic since 2005.