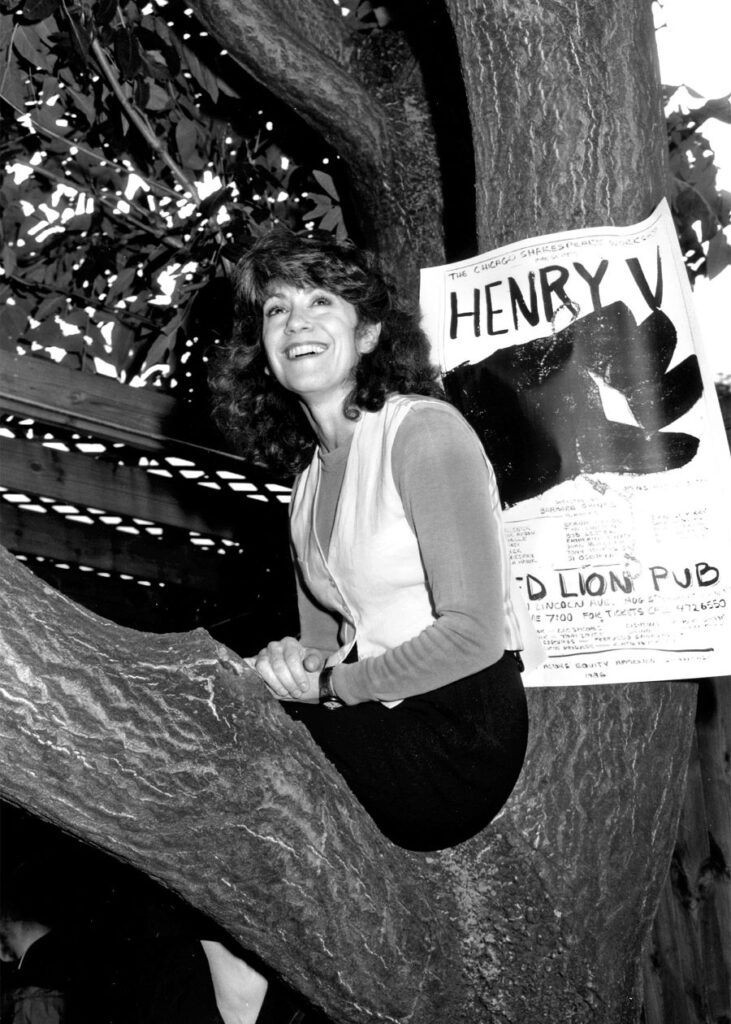

From the rooftop of a Lincoln Park pub to the staple theatre at one of Chicago’s most recognizable landmarks, boasting a facility that completed a $35 million repurposing in 2017, the entire history of Chicago Shakespeare Theater has been guided by the hands of Barbara Gaines. At the end of June, Gaines is set to step down from the company she founded 37 years ago, with her successor to be named later this year.

The trajectory for the theatre basically follows the quintessential Chicago dream: It began with a group of 19 like-minded artists performing on the rooftop of Chicago’s Red Lion Pub in 1986, who then transitioned into a residency at the Ruth Page Dance Center the next year, initially only producing one show a year due to budget constraints. By 1990, Gaines had found a long-term leadership partner in Criss Henderson, who himself stepped down as executive director at the end of 2022 after 33 years with the company. By the turn of the century, Chicago Shakespeare had established a flagship campus on Chicago’s Navy Pier. All the while, the company’s offerings grew from exclusively Shakespearean productions to include musicals, world premieres, and hosted artists from all around the world.

During her tenure, Gaines directed 60 productions, including 33 Shakespearean titles and six world premieres. Now Gaines, 76, readies for a pivot away from decades of leadership, eying spending more time on personal projects (like a new show she’s workshopping with composer Joriah Kwamé and playwright Lauren Gunderson—a wicked Shakespearean prequel whose premise I won’t dare spoil here). Earlier this month, Gaines took time to reflect on the history and growth of Chicago Shakespeare and what changes are in store for herself and the company she loves. The following conversation has been edited for clarity and concision.

JERALD RAYMOND PIERCE: I would first love to know how you’re feeling as things are winding down during your final month with the company.

BARBARA GAINES: I’m feeling a bit emotional, I would think is the best description, on every level. I think everything is heightened now. Everything should be a musical: I should be singing to you, because my heart is so full. You know what, Jerald, I know that this is the right thing to do. There is no doubt in my mind. I thought I was going to leave in 2020, but COVID got in the way. I realized in 2019 that yes, I think I’m done here.

I’m going to miss all these people, these phenomenal souls that I get to come to work with. But I’m not going to miss all the things that are part of the job. You see what I mean? I would love to work on projects but not have the weight of a big theatre, and the weight of worry, and the weight of raising money—all of the stuff that any artistic director will do. So now I can get back to just paying attention to how I began, in a way, just being a director and just giving it everything.

I totally understand that kind of impulse to want to be able to focus on your own projects rather than the whole. It is a big role.

Yes, it’s a big role. You give all of your love to the theatre, to all of the souls that work within it, and to all of their families. That’s just the way it is. And it’s been the greatest honor of my life, being with these wonderful people. It transcends everything else, really. But I want to be able to read a book from cover to cover. That’s my goal. I want to work, but what I really want for Christmas is to read a book from cover to cover.

You were able to revisit The Comedy of Errors earlier this year as your last official directing project as artistic director, a return to a 2008 production that featured a new frame written by Ron West. Because you mentioned that you were thinking about leaving before the pandemic, was The Comedy of Errors always the choice for your final show?

Very good point. No, I think I was going to end with Cymbeline, which is one of my favorite plays. Which, actually in 1989, a few years after we started, literally not figuratively, saved the life of the company. We only had the money for one play a year. So the first year [at Ruth Page Dance Center] was Troilus. The second year, Antony and Cleopatra. And then we ran out of money. I went to the board of directors, a small group of stalwart generous souls and risk-takers, and I said, “We start rehearsal tomorrow [for Cymbeline]. We don’t have any money for actor salaries or crew. Can you help us?” And they did. It ended up, long story short, winning Jeff Awards for best production, best this, best that. It put our name on the map. It just exploded because of Cymbeline. It’s such a great show; it can be both painful and hilarious.

That was going to be the last. Then COVID came, and then we all got really depressed. We lost people we loved, we were in isolation. We did everything that theatre people never do. There we were by ourselves, right? And I thought, I felt, when I had to make this decision—what was I going to do for this final play?—I put Cymbeline aside because everyone I knew was so sad. I thought maybe I could give a gift of laughter. Maybe we could make people laugh. And we did. I know we lifted the spirits of thousands and thousands of people, and that was my goal.

And then I was lucky enough to have some people from the show we did 15 years ago return. So it turned out to be one of the great other just treasures of my life, working with those people, knowing that it’s the last Shakespeare I’m going to do here. And maybe the last Shakespeare ever. I mean, I don’t know. The projects I have coming up may be related to Shakespeare, but they’re not Shakespeare.

But that feels right too. Not many people have been able to direct Troilus, or Cymbeline, or Richard III, or Henry V three times. It’s been such a gift to be able to revisit plays, because you never get it all. There’s always so much to learn, and you just go, “Oh my God, I never saw that line before. I swear to you, I never saw it before.” It shows that when we get older, when we change, texts change, because what I could understand when I was 35 hardly seems important now that I’m not.

As we talk about your work and being able to revisit these Shakespearean plays, the word that kept popping up as I read about your work was “populist.” Terry Teachout was quoted in the release announcing your retirement as saying, “Barbara Gaines is, in the very best sense of the word, a populist, a true believer in the power of the classics to speak directly to contemporary audiences when staged with sharp immediacy and infectious gusto.” And Chris Jones, in his review of your most recent Comedy of Errors, referred to you as “a populist Bardologist if ever there was one.” When you hear a phrase like that as people refer to your work, what does that mean to you?

I don’t know what that really means. That’s the truth. But you know what? When I was 18 years old, I read an essay that James Baldwin wrote about Shakespeare in 1964. James Baldwin changed my life. He became like the North Star. He taught me what an artist is and what you have to devote of yourself all the time, never stopping. It’s called “This Nettle, Danger.” It was months after President Kennedy was assassinated. And in this essay, he combines jazz, his role as an expat, racism, theatre, Shakespeare, to ultimately our responsibility as artists, what we do.

So I would say, maybe you’re talking about what you see in the audience, maybe an effect of the work. But the work is so personal and intimate. I think James said at the end of that article, “The people are not responsible to the artist. It is the artists that are responsible to the people.” We are there to discover. We are there to show that whatever is happening to someone else is also happening to me.

I think he says it better, but it’s a mystical journey. What affects you, if I hear about it, is going to touch me and change me. It has to. That’s opening yourself up indeed: for pain, for more joy, for more richness in your life, and to a well of empathy. And you are a witness. That’s what [Baldwin] gets to finally. Artists, we are witnesses to time. We are witnesses to your life. And we have to in some way share that with our work, whether it be writing, directing, painting, singing. That’s our job.

So when I hear phrases that people use, that’s fine, but it’s not the work. It’s not anything about our journey. Our journey, I think I’m speaking for many artists, is so deeply private sometimes we don’t understand it ourselves.

When I was reading your statement from when Chicago Shakespeare initially announced that you were stepping away, where you talk about 19 artists on the rooftop of Red Lion Pub, I just kept thinking how that reminds me of my first production in the city as an actor, in the back room of a random pub. How do you maintain that sense of community and that sense of camaraderie when you continue to grow from friends in a room at a pub to the established theatre that Chicago Shakespeare is now?

First of all, I started out as an actress. So when I’m with actors, I’m home. I’m just home. I don’t have the desire to act anymore, that muscle atrophied, but being in a room with people I’ve worked with for years, or new people who are equally as treasured in my heart, I feel like that’s the moment of sacredness. It’s sacred, and it’s fun. I love that, “sacred fun.” When we put those together, it’s fabulous.

The hardest thing is to grow. It is just difficult because, if you go from being an actor to being an artistic director, my total responsibility, as opposed to only me, is everybody else but me. To encourage work, to nurture artists. I mean, I don’t think I was a very good artistic director. I have to be honest. I know here we have this phenomenal building. I had a great executive director, Criss Henderson. We were, when we were working together, a good team. So there was a vision. But I think the most difficult time for me internally is growth, because you have to do things for the organization now, and for all the people within the organization, which are very different from 19 people on the roof of a pub. It has nothing to do with that. I mean, you have to keep that inside, of course it never leaves you. But you have to do other things. You have to raise money. You have to be an outward spokesman, an ambassador to the theatre, all these things that really, in a way, nourish the art in fertilizing ground. But it removes you a bit from the center of making art. It has to, because nobody can work 24/7. Although we try in the theatre, don’t we? It’s an unhealthy way to be.

I think the hardest thing to keep as an artistic director is your own dream time, because we’re watering as many flowers in a beautiful garden as we possibly can, and you often forget to nourish your own.

As you think about the next hands that will be guiding this institution into the future, is it hard, as a founder, to cede control over this child you’ve raised?

In theory, when I look at it as a whole, it is my gift. I am thrilled to be able to give this theatre to the next generation of theatre people. That makes me really happy. I mean, we’ll see what happens. Will I be frustrated by decisions that are made? Maybe. But I’ll be very far away from it. Remember, I’m going to be on my deck reading a book from cover to cover—that’s going to keep me very busy—or in rehearsals. I would love it if I could look back on this in years and see leaders who are treasures. Staff, the same kind of charisma they have now. I don’t know. It’s like an unknown world. What will it be like not having to get up so early in the morning and getting home so late at night? I have no idea.

Looking back over the decades of work, one thing I wanted to ask you is how you went about growing from a company solely focused on Shakespearean productions to a company that then produced Shakespeare-adjacent shows and then completely new works? How do you build out from starting at a Shakespearean base?

I think it all has to do with the people you start with. It’s the artistic team. It was the whole team that worked together to make sure that happened. I mean, Rick Boynton [creative director since 2005] is a treasure. His specialty is musicals and he also has a gift for dramaturgy and new plays. We are so fortunate to have that kind of person. I would say he’s a metaphor: We have talented people in every layer. When I started the theatre and we had no one, I made sure that we went to the best people I could hear about. If we needed a special effect, I would make sure we went to great special-effects people. If we needed help designing or executing a design—remember, there was no money, you just have to understand—I went to Max Leventhal, who was, at that time, the technical director at the Goodman. We started this because of other Chicago theatres. I would say, “I don’t have any costumes. I don’t have a place to audition.” Victory Gardens helped us there. DePaul helped us. I just asked, and nobody said no. We actually built the Troilus and Cressida set at one of our board members’ homes in Chicago in a garage. It was because we wanted this theatre. Everyone, all those people surrounding that Henry V on the roof, wanted Chicago to have a Shakespeare theatre.

And then, because Shakespeare is so rich, it’s like you can’t have Shakespeare three times a day. At least I can’t. Like chocolate mousse: I love chocolate mousse, but after one serving I’m fine. Or maybe one and a half servings. But Shakespeare is also very rich just in terms of density. And being on Navy Pier, it made perfect, perfect sense—the summer is filled with children and families, so why wouldn’t we do a family musical in the summer? Some of these things were pretty obvious because of our location.

Then, in 1989, I went for two or three weeks to Czechoslovakia to see theatre. I saw some of the most amazing theatre in tiny villages nestled in mountainous areas. I saw great theatre in Bratislava and Prague. It was a feast. But on that trip in 1989, I realized that international theatre was sensational. I had also seen, in the mid-’80s, Jane Sahlins create the International Theatre Festival of Chicago, and that blew my mind away, because I saw things that I’d never seen before. Different styles, but all with one thing in common: the radiance of creativity. I didn’t have to understand the language, because it was all so clear. And that was the beginning, I would say, of us loving and falling in love with the great theatres of the world.

When you look back over your career, over leading this institution, if you had to pick one thing to hang your hat on as your proudest moment, or the thing you’re most proud that Chicago Shakespeare achieved, what do you point to?

The thing that I feel is something that fills me with joy, as opposed to pride, is that we brought to this city Troilus and Antony and Cleopatra and Cymbeline and King John and all the Henrys—they know Brutus, they know Imogen, they know Miranda—that those wonderful characters and themes are making a ripple effect with over 2 million students that have been to this theatre, that they loved those shows.

I remember right after 9/11, it was literally maybe a week after 9/11 when we could go back to work, we were doing Richard II and it was all inner-city schools that day. And this wonderful young man said in the talkback, “Oh, I love the line about crying onto the earth.” And the line from it, Richard says, “And with rainy eyes let us make sorrow upon the bosom of the ground.” I totally paraphrased that—butchered it. [Editor’s note: “Make dust our paper and with rainy eyes / Write sorrow on the bosom of the earth”—pretty good paraphrase.] But that he, that beautiful soul that I was talking to that day 20-something years ago, that he felt that line, was all you had to give to me as a thank you.

There are thousands of people who’ve heard the lines of Shakespeare and took away a nugget like that. It’s the ripple effect of Shakespeare and the ripple effect of all those he was able to touch. So I think that’s it. I think it’s the work itself touching the souls of people that happen to be in those rooms here. That’s the greatest feeling in the world.

Jerald Raymond Pierce (he/him) is the Chicago Editor for American Theatre. jpierce@tcg.org