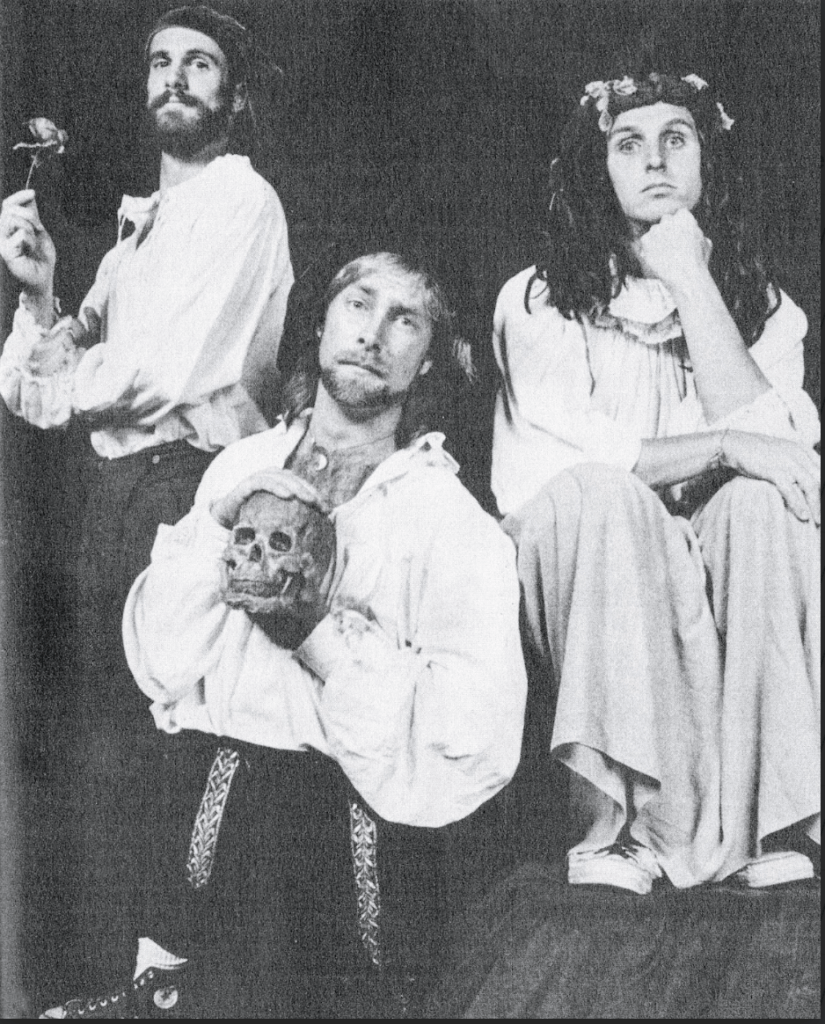

In August of 1987, in a dark, steamy, converted church basement that served as a venue for the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the global theatrical juggernaut that is The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (abridged) first tested its legs. “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players,”’ I intoned from the light of a pin spot. “And one man in his time plays many parts.”

Since those humble beginnings, The Complete Works, wherein three actors indeed “play many parts” in a foolhardy attempt to perform all 37 of Shakespeare’s plays in a single evening, has been translated into 32 languages and seen two-Off Broadway productions and a West End run that currently stands at #4 on the list of longest-running West End shows of all time.

So clearly it needs some fixing.

I and my co-authors Daniel Singer and Adam Long have undertaken major changes to the text several times over the years. Originally just an hour long, the play’s first revision came out of the necessity of expanding it to serve as a full length show for booking tours. We added a silly speech by Daniel—ostensibly a member of the “house staff”—offering the helpful advice that seat cushions could be used as a flotation device, followed by a bombastic, evangelistic “Preface” for pseudo-scholar Jess, and finally, a “Life of William Shakespeare” that goofball-savant Adam manages to mix up with some research on Adolf Hitler. In 1988, we expanded our original silly gag about Othello—Adam stabs himself with plastic boats because he thinks “a moor is a place where you tie up boats”—when Adam and I wrote an “isn’t it funny when white guys do hip-hop?” number called Rap Othello.

By 2007, all three of us author/performers had hung up our tights and licensed the script. Unlike almost any other play still in copyright, productions of CWOWS(A) are not just allowed to alter the playwrights’ original text—they are commanded to. The acting edition’s Authors’ Notes tell the performers to call each other not Jess, Adam, and Daniel, as scripted, but by their own names, playing exaggerated versions of themselves to bring their own quirks, talents, and vulnerabilities to the forefront. Watching other stock, amateur, professional, academic productions sprout up all over the planet, we learned something: The theatre world is infinitely more diverse than three suburban white California dudes ever imagined. We saw productions with casts that were mixed-gender, ethnically diverse, all-woman, all-queer—you name it. And while the quality of those shows varied, there was zero correlation between the ethnicity or gender of a production and its ability to make audiences laugh and think. With one exception: All-white, all-male casts felt, well… pale by comparison.

in The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged); photo credit Peterson Creative Photography & Design.jpg)

In preparing a new 20th-anniversary acting edition in 2007, entitled The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (abridged) [revised], Daniel and I somehow missed that crucial point. We focused on updating the tone of the humor. In the post-Book of Mormon, post-Rent world, we made it raunchier. F-bombs were dropped. The drag and homoeroticism inherent in Shakespeare’s comedies got a full airing in our mashup of all 16 Shakespearean comedies into a single “lump of hilarity.” Yet the base characters of Jess, Daniel, and Adam remained white and male. The comedic tropes in Romeo & Juliet were still a straight guy with a screeching falsetto in a dress, a rapey male Romeo, and an uncomfortable same-sex kiss. And there was still a rap interpretation of the now “Afro-Italian” Othello. “Here’s the story of a brother by the name of Othello/He liked white women and he liked limoncello.” Ha-ha.

Then came #MeToo and #Black Lives Matter.

In recent weeks, retroactive cleansings of Roald Dahl and James Bond have made headlines, but since the summer of 2021, Daniel and I have tackled the project of de-gendering and anti-racializing the script. Not Shakespeare’s works themselves, but our parody of them. Gone are the constant gendered (as well as classist and ageist) fourth-wall breaks addressing the audience as “ladies and gentlemen” or “you guys.” Now it’s “friends,” “people,” or “folks.” The volunteer who is conscripted to play Ophelia is asked for their name and pronouns before being asked, “Do you mind if we call you Bob? It’s a lot easier.” In Adam’s “Life of William Shakespeare,” Hitler and the guaranteed laugh line “Shakespeare invaded Poland, thus precipitating World War II” is replaced by Abraham Lincoln and “Shakespeare signed the Emancipation Proclamation, thus supposably freeing the slaves.”

Is “Shakespeare invaded Poland” the more perfect punch? Perhaps. Is it worth triggering survivors of the Holocaust and their descendants at a time when deadly antisemitism is on the rise and a dictator is invading Poland’s next door neighbor? We believe it is not.

At least, most of “us” do. One of the three members of the original writing team, decrying “woke” ideology and cancel culture, insists that:

1) Much of the show’s comedy comes from it being three guys.

2) Cross-dressing is just funny.

3) The Hitler joke slayed when performed in 1990s Jerusalem.

My counterarguments?

1) So who’s going to do the genital exams at auditions?

2) It isn’t funny to gender-transitioning people.

3) Jerusalem in the 1990s is, sadly, not the same as America in the 2020s.

Whether via sheer cussedness or the righteousness of my cause, I prevailed, and the CWOWS (abridged) [revised] [again] acting edition went live on Broadway Play Publishing’s website in August 2022, sans Hitler. It is currently playing with an all-female cast at the Venice Theatre in Florida through May 21, and will soon run at American Shakespeare Center in Virginia May 17 to June 4.

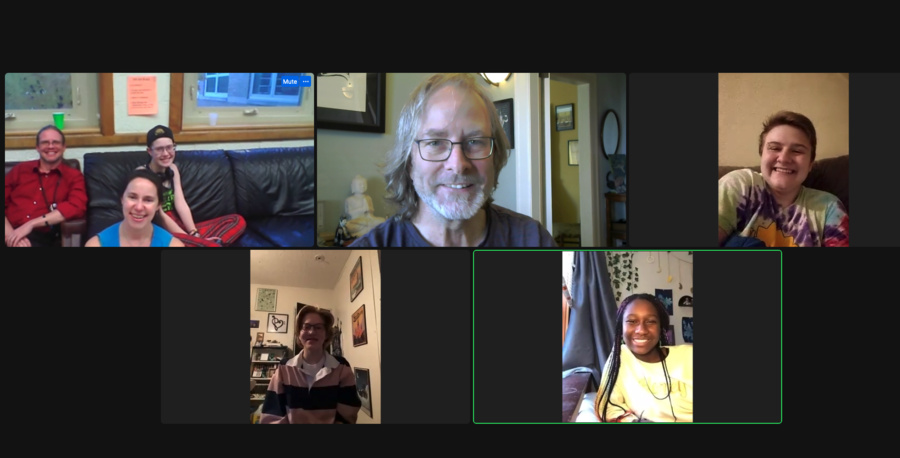

By chance, the first performances of the new script—its world premiere, unbeknownst to the cast and crew—took place at Brattleboro Union High School in Vermont in September. The show was double cast, and of the six performers, two identified as trans and at least one as gay. Mariam Abena Diallo, the 17-year-old playing the “Jess” character (who gets the plum title role in Hamlet), was a Black girl. We couldn’t have hand-picked a better focus group for the new material.

When I reached out for feedback following the show’s short run, director Rebekah Kirsten replied, “I went online to get the rights for [the 2007 version], and when I found the 2022 version, I was really psyched, because all of the major things that I was planning to update had been reworked—thank you!”

A subsequent debrief with the cast via Zoom was a screenful of happy faces. To a person, they thanked and commended us for diversifying the show and giving them a voice. Asked if there were any changes they’d like to see before the script goes to print, one of the trans actors took exception to just one phrase, “female genitalia.” “I don’t want anyone,” they said, “even me, to be thinking about my genitalia while I’m trying to act!” they said.

Some weeks later, I found myself at the first professional production of the show on the East Coast, by Baltimore’s Chesapeake Shakespeare Company, a company that had extensive previous experience with the show. Although excited about the revisions, the theatre’s executive director told me that she thought that Romeo & Juliet suffered from their having cast a woman in the Adam role, thus losing the guy-in-a-dress yuks. To which I responded, “If you think it’s funnier having a guy play Juliet, cast it that way. But then maybe have a woman play Romeo.”

Because, at the risk of rewriting Shakespeare: One person in their time can play many parts.

Jess Winfield was a founding member of the Reduced Shakespeare Company and a co-author and original cast member of The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (abridged). He’s also an Emmy award-winning writer/producer, published novelist, and an author and editor at AMERICAN ROAD magazine.