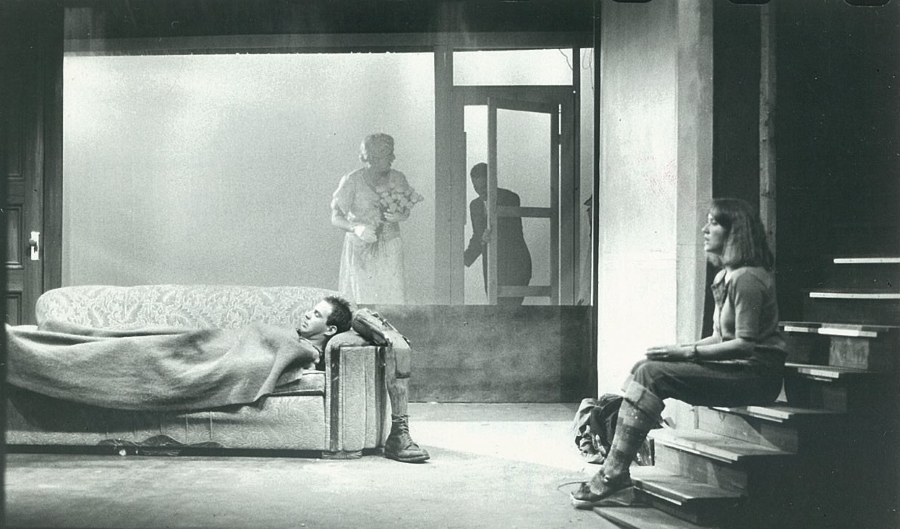

The first Sam Shepard play I saw, in 1982, was Steppenwolf’s legendary production of True West. I was 18 and I didn’t know what the theatre could be. But I could not take my eyes off John Malkovich and Gary Sinise. They gripped me: the visceral rage punctuated by humor; the sheer wreck of the stage; the rodeo of betrayal and disappointment. I can still see Sinise and especially Malkovich, the successful Hollywood writer and the petty criminal, not just trade places but explode into each other, scorching themselves, the set, the American dream. There was something not just form-defying but anti-form about it.

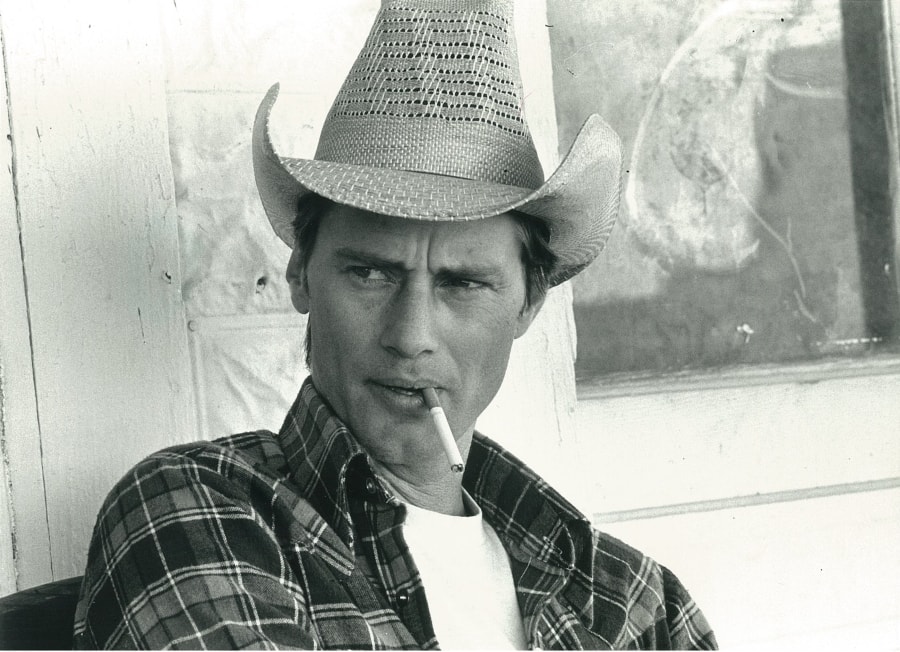

Back then, it didn’t bother me that the two central roles were men and that the mom and the agent were foils more than people. Dismissals like “toxic masculinity’’ were in the future. What impressed me was the display of emotion and the shape of the play, especially its collapse. After I had seen a few of Shepard’s other plays, I came to understand that these collapses, as much as the world he came from, is one reason Shepard never fit into the mainstream American theatre. And still doesn’t. Another is his origins. He belongs to a group of restless thinkers, artists, exiles—outsiders of a kind that doesn’t exist today. The cliché was cowboy, but to me Shepard seemed Whitmanesque.

Shepard died of ALS in 2017. And because the theatrical zeitgeist has shifted so dramatically since then, I wondered if his plays could still do what Suzan-Lori Parks named as his ability to “track the epic mythic raw American thrum.” Would they still be performed? Would young artists even read them? At first, as I was researching for this review, it seemed like one obstacle to Shepard’s survival in the 21st century had receded. During his lifetime, he—like his icon Samuel Beckett—was not inclined to see his plays cast in any way except as he imagined them: dissolute Western outsiders, mostly white, mostly men. In 1980, he would not let JoAnne Akalaitis direct True West. He stopped a small 2004 all-female staging of that play in New York, as well as a production of it that Ethan Hawke was working on and that would have starred Martha Plimpton and Marin Ireland (Hawke later staged a successful Off-Broadway revival with Ireland but not Plimpton).

But since Shepard’s death, there have been two unconventionally cast productions of True West. In the summer of 2019 came Steppenwolf’s critically acclaimed revival with Jon Michael Hill and Namir Smallwood as the brothers—the same pair who starred in Antoinette Nwandu’s critic pleaser Pass Over. And a few months ago, the None Too Fragile Theatre in Akron’s well-received version of the same play with the brothers cast as sisters and the mom as a dad (though it was not authorized by the estate).

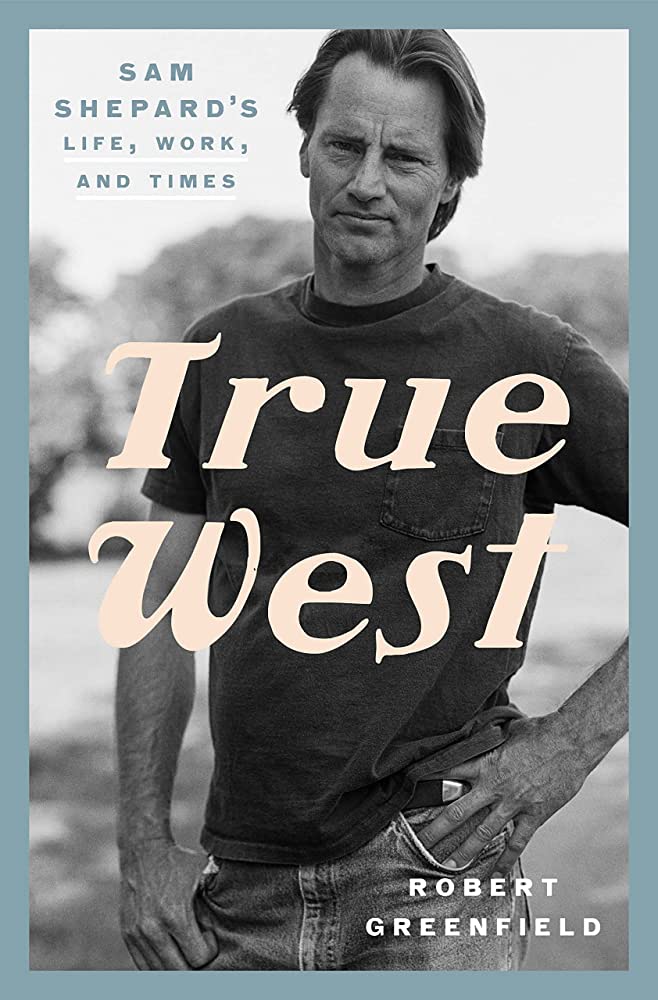

True West, Robert Greenfield’s new biography of Shepard—he was in more than 50 films and wrote 55 plays—does not address the question of how these plays will be performed in the 21st century. But this, the fourth biography to be published about Shepard, does deliver something new: It is the first one about Sam Shepard the icon, whereas the previous biographies chiefly treated Sam Shepard the playwright. This makes sense, since Greenfield formerly worked as an editor at Rolling Stone and has written many books about rock legends.

That is not to say that True West scants the theatre, exactly. Greenfield, who has written many books about rock ’n’ roll legends, doesn’t just take his title from Shepard’s play; you could even say the play is a template for the biography. Greenfield’s conceit is that the pieces of Shepard’s hyphenate artistry make up a fragmented whole, as the characters in his plays struggle to do. Here, Shepard’s shifting from theatre to rock ’n’ roll, then film, and back, is driven not just by money but by restlessness and demons. While Greenfield repeats Shepard’s famous saying that he would have preferred to be a rock ’n’ roll star, and recounts in great detail his stint as drummer in the Holy Modal Rounders, as well as his collaborations with Dylan and The Stones, he is clear that the theatre was Shepard’s home.

Greenfield treats Shepard’s romantic life in a similar way. Yes, he was involved with many women, many of them celebrities, including Patti Smith and Jessica Lange, whom he married. Joni Mitchell wrote “Coyote” about him. But here too his restlessness was an effort to escape his past (even as he repeated it).

That Shepard became a playwright at all seems like a miracle, given his ancestors. His alcoholic grandfather lost their farm and was reduced to selling Hershey bars door to door. Born Steve Rogers in Illinois in 1943 to a violent, alcoholic Air Force father and a schoolteacher mother, Shepard barely escaped Pasadena, the town he grew up in. Greenfield reports that many of his uncles came to bad ends, and that Shepard’s father set a mattress on fire while drunk and beat Shepard with a belt buckle. Greenfield also points out that Shepard’s father, who died in a car accident in 1984, was never as much of a cowboy as his son portrayed him. He loved Lorca, briefly worked for The Chicago Daily Tribune, and aspired to be a writer.

Shepard fled home early, dropping out of college to join a traveling theatre troupe, and landed in New York at age 19. There he became reacquainted with an old high school chum, Charles Mingus III, the son of the musician, and wrote plays for Off-Off-Broadway theatres: Genesis, Caffé Cino, La MaMa. He worked with Joe Chaikin. He began to receive rave reviews and win awards. Always he had a habit of self- mythologizing, like a lot of outsiders who struggle once they’re inside.

That self-mythologizing positively surges through his early plays: Cowboy Mouth, Suicide in B Flat, Action, and La Turista, all dashed off while waiting tables at the Village Gate and doing drugs. Lacking plot, character, and motivation, they appealed to ’70s-era theatre lovers above and below 14th Street, with their echoes of pop art, comics, rock ’n’ roll, and the Beats. Yet Greenfield is not the first writer to point out that Shepard was hardly a theatre newbie: An apocryphal story has it that back at community college, a frat brother handed him Waiting for Godot. Greenfield adds that Shepard also saw the movie of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, released in 1962.

As early as 1968, Shepard had turned to Hollywood, working on a disastrous Antonioni film, Zabriskie Point, and writing screenplays for concert tour films for The Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan, with whom he would later co-write the 11-minute song “Brownsville Girl.” He married the actor and composer O-Lan Jones before he met Patti Smith, with whom he had an affair and wrote the play Cowboy Mouth. He encouraged her: “Kick it in, Patti Lee. I’ll bail you out,” Shepard told her, referring to a window. But soon New York began to alienate him, and he fled to London, where he met Peter Brook, studied “the work’’ of George Gurdjeff, and read Brecht and Mayakovsky.

For much of the rest of his life, Shepard shifted from one world to another. He began to act in the movies, playing a farmer in Terrence Malick’s 1978 Days of Heaven, and later Chuck Yaeger in The Right Stuff. He co-wrote the Wim Wenders movie Paris, Texas. Yet he did not abandon the theatre, becoming a resident artist at San Francisco’s Magic Theatre. At the same time, the movies were key to his writing the brutal family plays that began with Buried Child in 1977, which won the Pulitzer in 1979. It wasn’t just that Hollywood money gave him stability; it also moved him closer to conventional storytelling. Likewise, Fool for Love was inspired not just by his affair with Jessica Lange, for whom he would leave O-Lan Jones in 1984, but by Thornton Wilder’s Our Town.

Greenfield includes striking portraits of Shepard’s kindness, especially to people brought low by physical frailty. He repeats the well-known stories of how the writer up-ended many relationships, including that of his dear friend Johnny Dark. But he also gives the reader several less known scenes about how Shepard rallied around his mother-in-law, Scarlett Johnson, after she had a stroke. Like his hero Beckett, Shepard reached to expose physical frailty in his work too. After Joe Chaikin’s stroke, Shepard worked with him on a radio play, War on Heaven. In his 1985 play, A Lie of the Mind (maybe my second favorite Shepard work), Beth, who has partly lost the ability to speak after her husband beats her up, quietly perseveres.

This is the first biography of Shepard since his death, and it fully documents what Greenfield calls the “utter dislocation” the writer felt in his last years. He knew something was wrong as early as 2000. But his inner tumult masked the illness. Estranged from Lange, he returned to drinking around then, even got arrested for drunk driving. His temper flared. Yet even after he was diagnosed with ALS in 2015, he continued acting and writing to the end.

Greenfield’s True West gives the reader more detail on many of Shepard’s wranglings (financial, industrial, personal) than previous biographies. And yet the man himself remains elusive. This is in part because Greenfield did not have the cooperation of Shepard’s wives or his children. The final picture of the man is a little blurry—like some of his plays, it might be noted, though in a biography, you want a sharper picture. Shepard himself would probably laugh and say that is not always possible.

Rachel Shteir’s book, Betty Friedan: Magnificent Disrupter, will be published in September by Yale Jewish Lives.