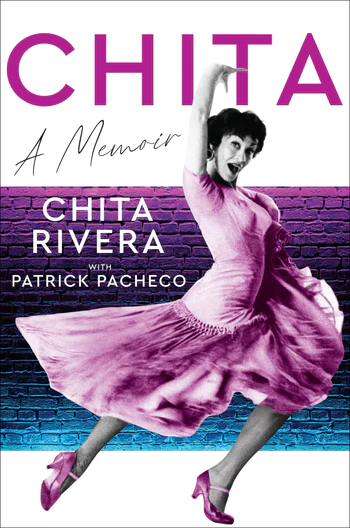

Upon hearing of the recent release of two new musical-theatre-related publications, I eagerly set aside time to dive into Chita, a memoir by Broadway’s legendary triple threat Chita Rivera, while somewhat dreading having to slog through dancer-turned-academic Ryan Donovan’s Broadway Bodies: A Critical History of Conformity, a scholarly treatise I felt obligated to tackle. To my surprise, I found Rivera’s book a bit of a snooze and Donovan’s riveting.

To be fair, Rivera’s memoir (written with arts journalist Patrick Pacheco) is sure to please many readers, particularly youngsters who harbor musical-theatre career aspirations and possess just a smidgen of knowledge about the history of Broadway musicals. It’s a quick, easy read that one can whiz through in an afternoon, and it’s written at a reading level that could be comprehended by any smart tween. Full of predictable anecdotes laced with trite sentiments, the memoir lacks nuance and offers little in the way of provocative insights or serious food for thought. It feels as though Rivera is simply recalling, rather than reflecting upon, the events of her life.

Best known for originating the role of the saucy Anita in West Side Story (1957), Rivera began her Broadway career dancing in the ensembles of Guys and Dolls and Can-Can, and went on to originate starring roles in Bye Bye Birdie (1960), Chicago (1975), The Rink (1984), Kiss of the Spider Woman (1993), and The Visit (2015). Though an accomplished actor and singer, it’s her magnificent dancing that makes Rivera such a memorable performer.

Born Dolores Conchita Figueroa del Rivero, Rivera had a Puerto Rican father and a mother of Scottish-Irish ancestry who, Rivera later discovered, was the daughter of mixed-race descendants of once-enslaved people. Rivera started her dance studies as a 9-year-old in her native Washington, D.C., at the trailblazing Jones-Haywood School of Ballet, a dance academy founded in 1941 to provide ballet lessons to minorities, including African Americans, who at that time were unwelcome at most ballet schools and commonly encouraged to pursue vernacular rather than classical dance forms. At 15, Rivera won a scholarship to New York’s prestigious School of American Ballet. She bunked with relatives in the Bronx and by age 19 had shifted her focus from ballet to musical theatre, when, on a whim, she accompanied a friend to an audition and got cast in the chorus of the Call Me Madam touring company.

Over the years, Rivera worked closely with many Broadway “greats,” including Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins, Bob Fosse, John Kander and Fred Ebb, Gwen Verdon, Liza Minnelli, and Sammy Davis Jr.—with whom Rivera had an affair while the two were performing in Mr. Wonderful (1956)—and she writes effusively about all of them. But her stories accumulate into a tiresome praise-fest from which Broadway buffs will learn little they didn’t already know. Contextualizing Rivera’s memories are facts about the history of the Broadway musical (likely contributed by Pacheco) that help create a flowing chronological narrative. Yet the book remains largely unilluminating. Even when discussing the events of her personal life, such as her short-lived marriage to Tony Mordente (one of West Side Story’s original Jets), the excavations of Rivera’s internal landscape prove superficial at best.

Chita does proffer a few surprises that make for interesting reading. I never knew that Marlon Brando played the bongos for jazz dance classes taught by West Side Story co-choreographer Peter Gennaro; that when Hollywood didn’t come knocking on her door when casting Anita for the West Side Story film, Rivera didn’t even ask to be screen-tested; or that the original script for Chicago contained bigoted slurs against Latinx people that were cut only after the show’s Philadelphia tryouts.

The finest parts of Rivera’s book are those that touch on issues of race, gender, and body types. She shares distressing tales of casting prejudices she encountered as a short Latina dancer. Yet as an author, Rivera adheres to conventional, and at times stereotypical, perspectives, attributing her periodic hot-headedness to her Puerto Rican ancestry, linking Mordente’s ardent jealousy to his Italian background, and admitting that, when casting male back-up dancers for her cabaret act, she was partial to Latin and Mediterranean types because “they had power and masculinity in their moves.”

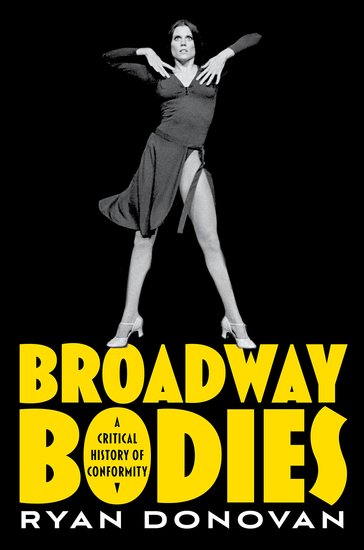

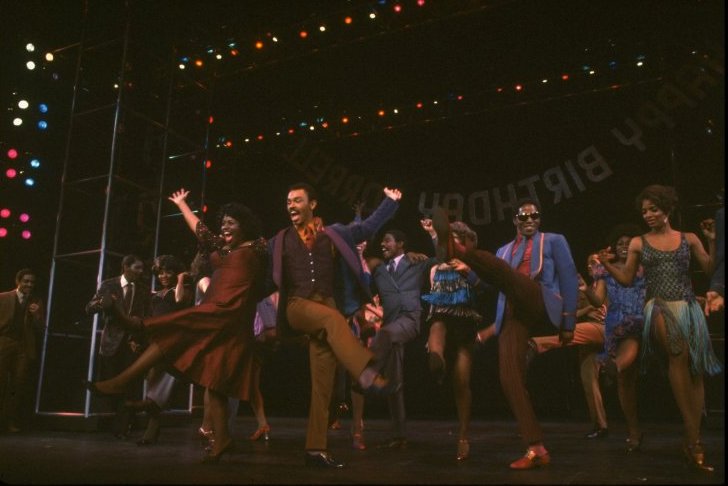

By contrast, Broadway Bodies delivers a critical assessment of how physical characteristics problematically impact the casting of Broadway musicals. Skillfully written in sharp, crystalline prose, the book comprises three case studies, each taking a deep dive into a musical whose casting demonstrates a particular type of body bias, then explicating that bias in a follow-up chapter via other relevant shows. A close look at Dreamgirls (1981) launches an examination of Broadway’s biases concerning size (specifically, fatness); La Cage aux Folles (1983), sexuality; and Deaf West’s revival of Spring Awakening (2015), disability. Noting that scholarly explorations of race and gender issues on Broadway have already been published (such as Warren Hoffman’s The Great White Way: Race and the Broadway Musical and Stacy Wolf’s Changed for Good: A Feminist History of the Broadway Musical), Donovan trains his lens on Broadway’s troubling prejudices within his three categories of concern. Nonetheless, because of the intersectionality often at play, race and gender aspects creep in and richly complicate his investigations.

The crux of Donovan’s criticism is that in terms of storylines, characters, and messages, Broadway musicals appear to wholeheartedly celebrate notions of inclusivity, equity, and social justice. Yet when it comes to casting, they are, in fact, quite exclusive and conformist in the types of physical bodies they employ. To those who point out memorable examples of seeing fat or disabled performers featured in Broadway musicals—fat women playing Tracy Turnblad in Hairspray, or Ali Stroker, an actor who uses a wheelchair, as Ado Annie in Oklahoma!—Donovan argues that, while non-conforming bodies have been cast in prominent roles, the vast majority of jobs available to Broadway musical performers are as ensemble players, and those roles are virtually always cast with non-disabled, conforming bodies.

The problem, therefore, is essentially a labor issue. And the labor concerns around casting, he writes, “usually become subsumed under ‘artistic license,’ providing cover for harmful and exclusionary practices.” Typing—casting personnel’s way of immediately eliminating people based on appearance—would be unacceptable in most professions, yet remains a norm in Broadway ensemble casting. While Donovan recognizes that casting practices have begun to change for the better, he feels the changes are coming too slowly and constitute isolated examples rather than trends. The way to spur significant movement toward casting equity, he argues, is to deepen our understanding of what has been going on in the casting of musicals over the last 50 years or so.

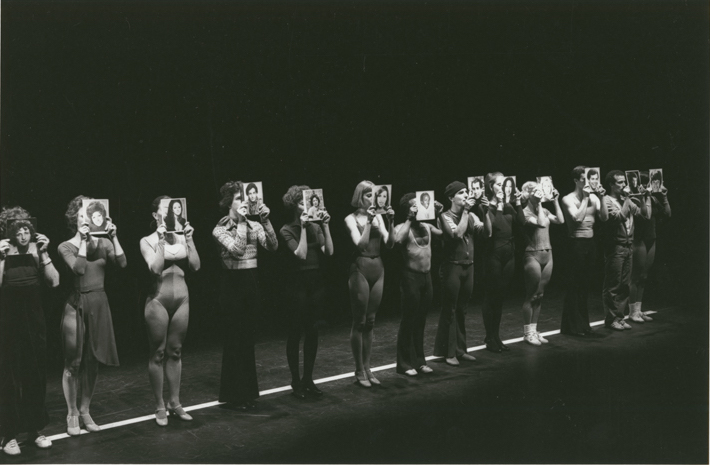

Though he acknowledges the long-standing relationship between physicality and casting, Donovan situates the roots of today’s standardized concept of a “Broadway body” in the emergence of the triple-threat performer—that economically desirable singer-dancer-actor whose multiple skills allow productions to hire just a single group of performers to take on the dual responsibilities of what used to be separate singing and dancing ensembles, while also serving as understudies for the show’s principal roles. He opens his book by delineating how A Chorus Line (1975) and its spotlighting of the extreme physical fitness of a dancer’s body initially set out to humanize dancers, yet ended up fueling the Broadway musical’s move toward ableism, the glorification of extraordinary ability above all else. Just as we celebrate virtuosic singing and dancing, Donovan explains, we’ve learned to applaud a straight actor’s ability to persuasively portray a gay character, or an able-bodied performer’s convincing depiction of a character with a physical disability.

A stimulating read, Donovan’s book sets out a wealth of perplexing new ways to think about the broad social implications of casting. For example, what are we to make of the resemblance between Broadway’s embrace of ableism and 19th-century eugenicists’ belief that “the lesser the ability, the lesser the human being”? Why is it that Broadway has never cast a fat actor as Cinderella, Nellie Forbush, or Eliza Doolittle, even though nothing about those roles inherently requires thinness, and more than two-thirds of American women are classified as overweight or obese? What should we think about the high level of uniformity demanded of the drag ensemble in the original production of La Cage aux Folles, which was cast with 10 cis men and two cis women, ostensibly to keep the audience guessing their gender? And why is it problematic to think of American Sign Language as choreographic, rather than recognizing it as a form of linguistic communication that shifts the definition of a triple threat to one who signs, dances, and acts? Does it matter that around 12.6 percent of the U.S. civilian, non-institutionalized population self-identifies as having a disability, while only 219 of the approximately 50,000 members of the actors’ union (a little over 0.4 percent) identify as such?

While Donovan’s book may feel overwhelming in all that it is asking us to consider, ultimately it’s a wake-up call for anyone interested in equity. It requires that we ponder what it is about ourselves that we really want our American musical theatre to reflect.

Lisa Jo Sagolla is the author of The Girl Who Fell Down: A Biography of Joan McCracken and Rock ‘n’ Roll Dances of the 1950s. A New York-based arts critic, she teaches at Columbia University’s Teachers College and at Rutgers University. Her essay on the Broadway musical Timbuktu! (1978) appears in a new book on Geoffrey Holder forthcoming from Duke University Press.