Playwright and Open Theatre co-founder Megan Terry died April 12 at age 91 in her adopted hometown of Omaha, Neb. Five decades earlier she moved there from the New York City avant-garde theatre scene that embraced her in the 1960s. The unlikely move was prompted by love, as she joined her life and creative partner, Jo Ann Schmidman, at the Omaha Magic Theatre. Remembered as a searcher, nurturer, pioneer, and calm creative force, Terry’s subversive feminist work influenced a generation.

“Megan Terry’s life as she lived it and her legacy are a force of light and energy,” said Schmidman, a director and playwright. “Her more than 50 published works for the stage have impacted theatre worldwide. Her plays are published singly and in prestigious drama anthologies and studied by high school and college students worldwide.”

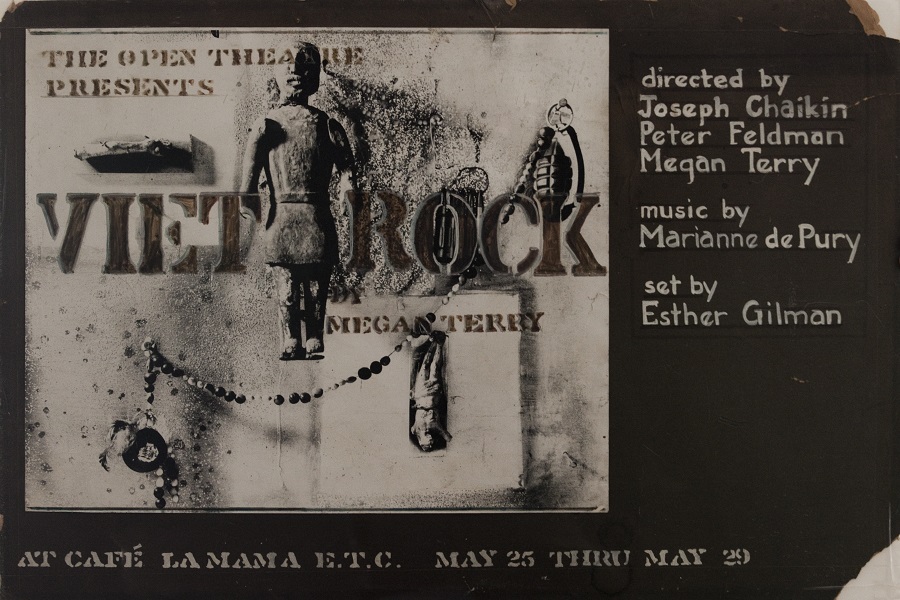

Terry grew up in the Pacific Northwest, cutting her theatrical teeth at the Seattle Repertory Playhouse and the Banff School of Fine Arts in Canada. The Yale and Guggenheim Fellow found a home for her plays at Café La MaMa in New York City. She and Open Theatre co-founder Joseph Chaikin changed dramatic arts with their theatre of transformation, said Elizabeth Primamore, author of the forthcoming book Daring Lives, Crucial Art: Five Women Writers in the 1950s.

Artist Sora Kimberlain said of her late collaborator Terry that she “pushed aspects of performance to new alternatives,” adding, “The result is a rich wealth of work that is an expansive vision about life, love, nature and the human condition—that propels the medium out of a traditional, structured box.”

Terry’s work won critical acclaim, and she received an Obie for Approaching Simone. Primamore said she also “revolutionized” theatre by being the first “to bring rock music to the stage in her play, Viet Rock, creating the genre of the rock musical.”

The artist continued being a provocateur in her OMT work with Schmidman, said Susan Carlson, a professor of English at the University of California-Davis. “In their boundary-bashing, energetic, loving, and community-based art, they managed to create a women’s theatre that absorbed the extremes of Midwest weather and the freedom of the vast, open heartland. Their theatre was wild, celebratory, and female. They performed pieces that combined text, sound, dance, music, light, images, and rhythm to surround the audience in a liberating, transitional space.”

The goal was self-exploration: to interrogate and set free the interior life of participants. OMT offered safe harbor for counterculture seekers in the ‘70s. “Many students were coming out of college looking for answers; Megan helped a lot of us find ourselves,” said OMT veteran Kris Simon. “One gift Megan gave me was a belief in myself. I always felt respected and loved by her.”

“Her eyes would search you until she found your heart. She had a nose for love,” said fellow alum, Rae Ann Schmitz.

Terry, who once played Peter Pan, possessed a personal magnetism that inspired others to come experiment and play. That pull led Schmitz to leave law school her senior year to join the OMT.

“I found a home in a world where everyone was welcome and the only price of admission was your mind,” said Schmitz, adding that Terry “breathed unconditional love into every word she wrote, and the audience felt it in between the lines.”

Artist Diane Degan also fell under the sway. “I walked in the doors of the Magic Theatre and I almost never walked out,” she said. Degan designed sets and toured with such Terry plays as Babes in the Bighouse. She vividly recalls Terry entering new performance spaces and yelling at the top of her lungs to test the acoustics.

A chance meeting in the late 1980s “literally changed the course of my life,” said Kietryn Zychal. “Over drinks in a Greenwich Village bar Megan praised Omaha for its cutting-edge theatre scene. She believed Omaha’s smaller size made it the kind of place where you could actually ‘get things done.’ She said, ‘Come on out!’ And I did.”

The way Terry’s plays never talked down to audiences, but challenged them instead, impressed Zychal. “She was raising consciousness about social issues (gender, the environment, mass incarceration) long before it was fashionable in a place where you wouldn’t think it possible. Megan had faith in Midwesterners’ intelligence.”

In OMT’s immersive, interactive milieu, Simon said, “Audience members were an active part of the play itself, not merely viewers.” Kimberlain said a piece wasn’t considered complete until the audience engaged with it and offered feedback.

Said Carlson, “The ensemble work was meticulous, as it brought audience members into this dazzling theatrical space in which, if brave enough, they could break through the expected, while a part of a community. Progressive politics were always present, always important, but not dominant.”

Terry’s imprint led Amy Lane to pursue a career as a director. “Megan was fierce, supportive, fearless,” said Lane. “She fostered my love for experimental, groundbreaking art and showed me that a career in professional theatre was possible.”

OMT actor David Brink said Terry was well complemented by Schmidman in a shared creative process. “Everyone talks about how kind and compassionate Megan was, but she was also really tough. You could not play her, or Jo Ann, ever. They were too knowing. Megan and Jo Ann were the first gay couple I ever met. They were the first working artists I got to be around. This was 1986. The world is much different today, and the mark they left on me is huge. It is a beautiful scar. They were beyond committed and expected a certain level of commitment from everyone. Not everyone could take the rigor of working there.”

Schmidman led “warm-ups” of intense yoga, recalled Schmitz, before “the company moved into workshop” mode, “when the creative process of improvisation, the invention of worlds, situations, and characters, came alive. Somehow Megan would capture the chaos and put it to words.”

OMT alum Holly McClay enjoyed what she described as Terry’s “Earth mother” presence. “She had a way of making one choose to do something that was her idea, but leaving you feeling you made the only correct choice. She always observed from the bleachers as the company workshopped whatever play we were birthing. She shaped the whole as we sweated through the details. Jo Ann was the fire and Megan was the stone ring that kept that energy useful rather than destructive.”

McClay remembers the couple “forcefully pushing boundaries and knocking down walls just by living authentically and unapologetically.”

OMT plays toured the Midwest and America, as well as the world. Terry and Schmidman closed their Magic Theatre in 1998 after a 30-year run and archived its work, documenting highlights in the book Right Brain Vacation Photos. Terry’s work is housed at the University of California-Berkeley.

Said Kimberlain, “Megan Terry’s work is timeless, her early pieces as contemporary today as they will continue to be in the future. Her tremendous inspiration and voice is forever present.”

Leo Adam Biga (he/him) is an Omaha-based freelance writer and the author of the 2016 book Alexander Payne: His Journey in Film.