Arena Stage was already a major U.S. theatre when Molly Smith took the helm in 1998, but the argument could be made that after 25 years in the position, she has not only maintained the theatre’s preeminence but bolstered it. She was only the third artistic director to lead the venerable institution since its founding in 1950 by Zelda Fichandler, who was succeeded by Douglas Wager. Smith’s background—as a leader of Alaska’s Perseverance Theatre, who had turned that remote venue into an unlikely new-play mecca—seemed to give her the frontier grit to stake her own claim on the Arena legacy.

Smith hasn’t looked back since. Among her signature achievements at Arena was the building of the new Mead Center for American Theatre and the Power Plays commissioning program, both of which cemented her main focus on new plays by American writers. As she related in a recent interview, this emphasis was not a given when she started out.

ROB WEINERT-KENDT: We spoke last fall when you announced you were leaving. Now one thing that’s on everyone’s minds is what percentage of audiences you’re all getting back compared to pre-pandemic. What are the indications you’ve seen at Arena Stage?

MOLLY SMITH: They’re extreme. It’s either a boffo hit, with tons and tons of people, or it’s small audiences. Either you have something like Ride the Cyclone that just did gangbusters, and extended by a couple of weeks; American Prophet did the same. And then there were two other shows that were good shows—but they weren’t events. That seems to be the thing that’s drawing people out of their pajamas right now.

A lot of theatres are announcing their upcoming seasons right now, even as subscription numbers have plunged. When you put your seasons together, did you feel pressure to make everything a stand-alone event, or to curate shows as a group with a connecting theme?

One figures out what the throughline of a season is after the season has been chosen. And if you actually are reflecting your hometown where the theatre is, then you’ve done your job—because that throughline will be about what’s happening in that city in one way or another. I know other people will choose seasons with ideas in mind, but that doesn’t work for me. And I do think that it has shifted into: Go bold or go home.

Does the 2023-24 season you’ve chosen have an overarching theme or themes?

The coming season is: bread crumbs for the new artistic year. So it has a sense of following a 25-year history, but doing it dynamically, so that the season rocks and rolls, starting out with something like Cambodian Rock Band, then a couple of commercial projects, a Power Play—it’s a robust season.

You mentioned the Power Play, Kia Corthron’s Tempestuous Elements. Which part of history is she looking at in that play?

The 1890s, and she’s focused on Anna Julia Cooper, an educator, a scholar, a feminist, African American. It takes place here in Washington, D.C., at a very famous school called the M Street School, which she ended up running. While she was doing so, there was a real push for the African American students to be studying in the trades as opposed to academics, which is something she mightily fought. What’s fascinating about the play is that Kia was commissioned probably four or five years ago, and here we are, in this moment in time where there’s now a desire to keep white students ignorant about what happened in the past, in terms of African American history—let’s keep them naïve so they don’t understand the country’s history. That is a throughline of American history.

How did the Power Plays get started?

The way I started on this is, I was commissioning people for president’s plays. So Tazewell Thompson wrote Mary T. and Lizzy K., about Mary Tyrone and Elizabeth Keckley, with a tangential guest part for President Lincoln. Then I spoke to Larry Wright about the idea of Camp David in terms of President Carter. So once I was into those two plays, I then moved into this larger idea of, What if we do every decade of American history? We’re going to hit some presidents, as we have. But it will be something that will look through American history, with touchstones in different decades, to give us an understanding of who we are as Americans. That’s where the idea was born. It started as a smaller commissioning program, then it moved into a 25-play cycle.

I didn’t realize it was doing the decade-by-decade thing, like August Wilson.

Yes, every decade of American history from 1776 to 2010. People within the organization wanted to package it as: These are the president plays, these are the women’s plays. But I was most interested in the decades. You probably know the Justice Scalia play, The Originalist, set in 1990. Camp David was really important, because Jimmy Carter came to see it, and I went out to interview both he and Rosalynn Carter, which was absolutely amazing. This year we’re doing Ken Lin’s Exclusion, about the Chinese Exclusion Act, and we have The High Ground on now, which is Nathan Alan Davis’s play about the Tulsa massacre. We commissioned him for that probably seven years ago, before most people knew about the Tulsa massacre, because, again, it was left out of history books, but then it was the 100-year anniversary in 2021, and suddenly people were aware of it. The happy news for him is that because he was researching in this area, he ended up with a two-part television series around it. I adore it when we can help support artists move from one medium to the other.

When we did Sovereignty by Mary Kathryn Nagle, which was about a combination of women right now and the Violence Against Women Act and tracking back to scenes with President Jackson and the Trail of Tears, I have to tell you, audiences would come out and say, “I consider myself an educated person, and I didn’t know any of this. I had to Google it at intermission, and I found out you were actually telling the truth.”

I know that when you came to the Arena, one of your main agendas was to make it a home for new American plays. I wonder if that vision brushed up against the common wish for an equivalent to England’s National Theatre—as over the years some have wondered, Why doesn’t the U.S. have a national theatre too? Did you ever feel like Arena, being in the nation’s capital, was an obvious contender for that role?

I felt that with the creation of the Mead Center for American Theatre, it became, well, a center for American theatre. We have a focus on American writers and American artists; that doesn’t mean that we don’t sometimes bring in artists from other countries, but it’s driven from an American point of view. But I would say that the national theatre in America is all the theatres, all kind of focusing and charging together, as opposed to one in New York, one in Chicago, one in Washington. These are all important theatres, right? I think it’s the whole country.

Sure, but the thing about D.C., I hardly need to tell you, is that it’s the nation’s capital. So programming theatre for your local audience can’t help but project out with a kind of national voice.

Well, I think the difference is that Washington, D.C., is a crossroads for everybody to come to learn what it means to be an American. That’s why we have so many tourists here. They’re all over the 36 museums we have here, learning about American history. So it really makes sense to have a theatre focus this way too. Twenty-five years ago, when we did this, it was a shocking notion. People at Arena didn’t even want us to talk about it; they said, “What’s going to happen when people see we’re not doing Chekhov and Ibsen?” I said, “They’re gonna figure it out.” Many people felt as if the new-American-play focus was going to be narrow, and my continual argument has been that work in America is wide. It’s deep. It’s diverse. It’s exciting. It’s people of every nationality. And how thrilling to be that kind of voice in the nation’s capital. I mean, we built a whole center around that galvanizing idea, so it’s been something that has really fueled us.

I think because I came up at a time when it was more taken for granted that new American writing was something theatres should do, we forget how much many regional theatres really used to be all about classics and English plays.

And my argument was, why are we constantly looking over our shoulders at the Brits? Why aren’t we looking at our own backyard? Many people would say, it’s the level of the work. And I said: Let’s prove it.

It strikes me that yours is one of the few major theatres whose name literally describes your main space. Has that been confining or inspiring?

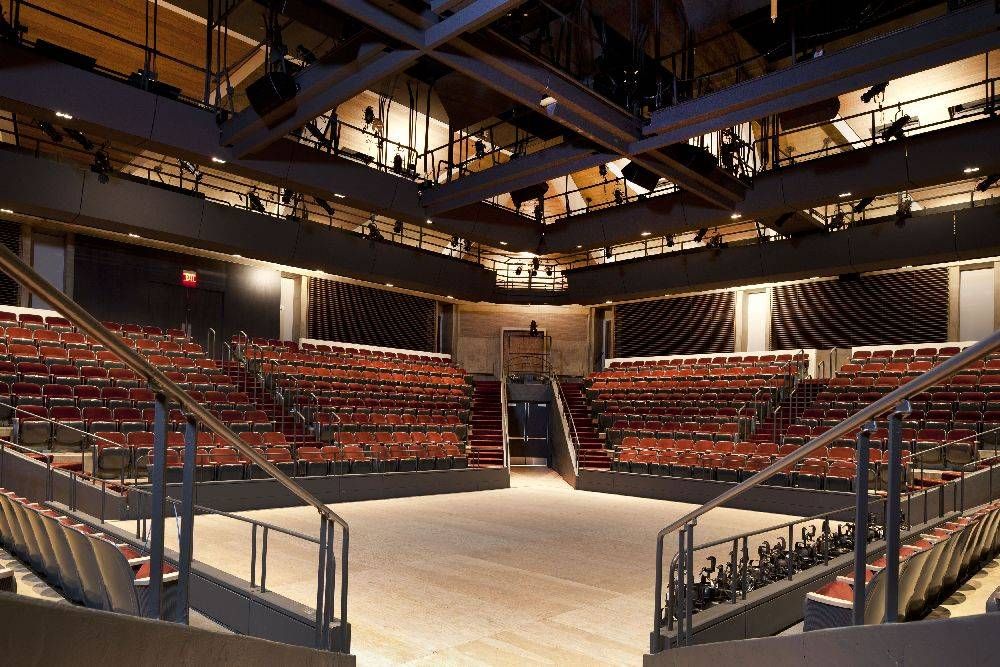

Well, we have three spaces, and each is an entirely different configuration: the in-the-round space, which is really in-the-rectangle, that seats 680. And we have the Kreeger, which seats 520, and that’s a modified fan-shaped space that comes out in the audience, and then we have the Kogod Cradle, which is 220, our smallest space and the only proscenium, but it can also flip into other configurations. But it’s thrilling to me. The arena was something that Zelda Fichandler created because she believed that was the theatre of the future—because it’s about community, it’s about seeing each other across the aisle. Community was a dirty word in the ’90s; it was a dirty word for many people in the ’70s. What they’d say is, “We’re not interested in community; we’re the professional theatre.” There was a very strong line of demarcation between those two. Now, of course, it’s completely switched, and it’s all about working with various communities. But yes, there is something that happens in the arena, because you’re responding to each other. It’s face to face across the divide through the actors.

I wonder, on a practical level, if you had to learn to direct in the round, and if you’ve developed a toolkit you share with directors when they come to work in your space.

I had directed some films when I got here, so I had a 360-degree brain. Choreographers usually do very well with it. But people who have only worked with strict prosceniums—there’s lots of conversations with them. They’re so used to the picture book, maybe occasionally a thrust, so it’s shocking to work this way. I often will teach people certain tricks I use so they can start building their own toolkit.

I won’t name any names, but I can sometimes tell when a director doesn’t know exactly what to do in the round, or in three-quarter, like at Circle in the Square.

Some don’t understand it. They just have somebody in the center turning around and around—I don’t think that works.

It’s all about finding a reason to turn, right?

Right. I call those reaction shots. If you can get those reaction shots, you open yourself up to a whole other side of the audience. What people don’t understand is that in the round, the voms—the vomitorium, the place where people come out and go back—are actually some of the most powerful spaces, because those are the areas where you are seen by the largest number of audience members. At the Arena, there are four different voms; if I’m at the top of one of those voms, I’m open to three quarters of the audience. That puts me in a total power position. Being in the center, not so much.

Your successor is going to be named any day now, and obviously you had no role in selecting them. But can you tell me, what do you think is the biggest challenge they’re going to face?

We might have spoken before about the revolution that started the American theatre. And that was started 75 years ago by really fierce people like the Zelda Fichandler and two intrepid women in Texas who believed that we could do great theatre in our own communities and move away from the tyranny of New York. In a way, that’s a revolution that’s been won, because how many theatres do we have now? 1,000? 1,200? I’ve been wondering for a couple of years—more than a couple of years—what’s the next revolution? I think we’re in it. So anybody who is taking over any theatre, or who is in the theatre business now—I think it’s going to take us 10 years to move through this particular revolution. It’s happening at all levels of the theatre right now. It’s pay for people. It’s We See You, White American Theater. It’s the #MeToo movement. It is about the way theatres are operating. It is about prices. Interestingly enough, it’s not so much about the work; it’s everything else around it that is really torquing theatres. Normally, it would be 10 theatres going through things, but now it’s all 1,200 of them. That’s why it’s so hard to see the future right now. It will start to settle, and then when it starts to settle, theatres will run in a different way than they had before. But we’re in the middle of the revolution.

I also feel like there’s a strong pull in the other direction—toward so-called safety, a return to “normal,” etc. I don’t think Zelda and those other founding leaders would be pointing that way if they were around today, though.

I think you’re exactly right. Any time I hear people say, “The way we used to do it,” I know we’re on the wrong track. I think, What can we do that’s the opposite? That’s different? People want to go back to what’s safe, what feels good, what isn’t scary. And the truth is, it is scary—lots is happening. Let’s buckle in and try to figure out what this next movement is. That’s why I’m saying it’s gonna take 10 years.

What are you most proud of in your time at Arena?

I’d have to answer that in three pieces. The first one is the creation of this new center for American work mean. Zelda called it the eighth wonder of the theatre world, which I love. It’s beautiful, and it works beautifully, and artists and audiences love it. I think the reason why is that we worked with architects who went from the mission statement of Arena, which has to do with deep and dangerous and the American spirit, and they also worked with our technical team on adjacencies, and why something had to be placed next to something else in order to make the theatre spin, so where the costume shop is is right below the rehearsal spaces, and very close to the performance spaces. Because we put everything under one roof, including our set shop, our costume shop, our prop shop, our admin—I think that makes a huge difference as far as a nexus of energy, of ideas.

Another one has to do with diversifying audiences. Twenty-five years ago, we started producing about a third of our work by artists of color, and that means that’s our audience as well. That’s really exciting to me. What you put onstage, within five years is the theatre that you become, and that’s the audience you end up with.

The third piece is, we started programming political work. Probably 20 years ago, when people were not programming political work, it was always, “Oh, the Brits do that.” I was desperate to commission people, but they weren’t interested in what was going on politically in the country. That’s all changed. So I feel like we were ahead of the curve on developing work that came out of the politics of the country. And that was important, of course, because we’re in Washington, D.C. I had a lot of arguments with people who said, “Oh my God, Molly, you don’t want to do that. That’s what people live in every day here.” I said, “Yeah, they live, sleep, and eat the Washington Post, so they’re actually going to be fascinated with what’s onstage.” It has ended up being a huge energizer for the theatre.

What’s next for you, Molly?

For four months, Suzanne, my partner, and I are going to travel. I have so missed traveling. Also, about a year ago, I went back to throwing pots. After 50 years, I went back to put myself in front of a wheel in a studio. I found that I remembered absolutely nothing from what I did when I was 18 years old. That was humbling and really exciting. I get to have a beginner’s mind; normally I’m an expert, and being a beginner is a real joy and a real pleasure. And I’m learning a craft solo, as opposed to everything I do in my life being group-oriented. This is just one on one, me and the clay. I liked the speed of throwing pots. Suzanne wanted dessert plates, so I made like 20 dessert plates of all different sizes.

Rob Weinert-Kendt (he/him) is the editor-in-chief of American Theatre.