Artist and entrepreneur Kira Troilo leads with empathy and heart.

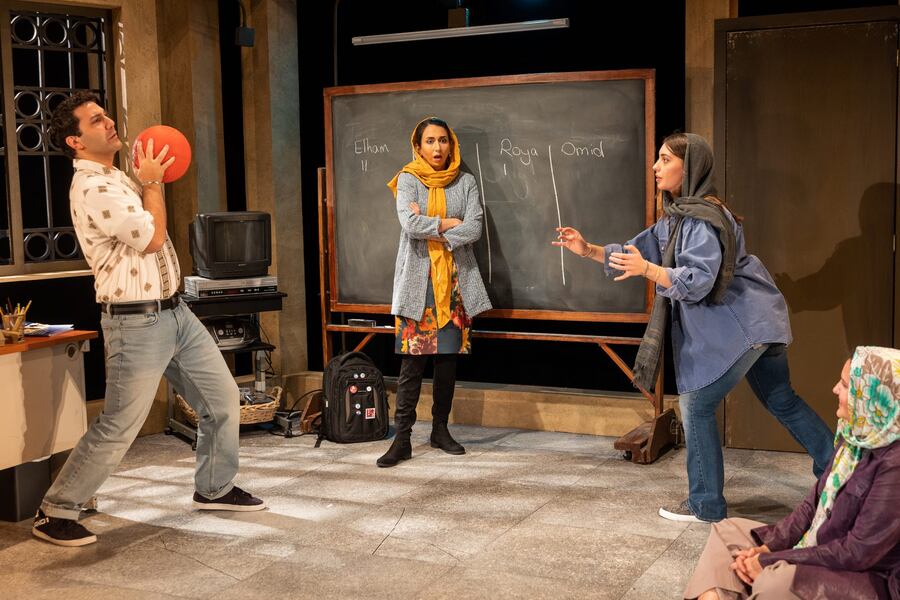

She has employed both attributes in her work with Boston’s SpeakEasy Stage Company, which recently staged three plays with intricate narratives centering on characters of color: Sanaz Toossi‘s English, Hansol Jung‘s Wild Goose Dreams, and Jackie Sibblies Drury‘s Fairview. These productions—with themes of division, racism, identity, and more—respectively took audiences to a classroom in Iran, to the bustling city of Seoul, and into the home of a suburban Black family readying for a birthday party.

Showgoers at these productions may not have realized how much work went into trying to get them right, but directors and actors from the shows say the behind-the-scenes work of Kira Troilo, an equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) consultant and the founder of Art & Soul Consulting, was particularly helpful in handling the cross-cultural issues raised by these plays with sensitivity and care.

The need for EDI in the theatre (and arguably any space where people work together) isn’t new. Still, when the emergence of COVID-19 shuttered theatres, and Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) artists banded together to pen the We See You, White American Theater (WSYWAT) statement seeking to “build anti-racist theatre systems” amid civil unrest after the death of George Floyd, it sparked an urgent need for real change across the field.

The work is critical for numerous reasons. As Troilo points out on her blog, “We ask artists to access an enormous amount of vulnerability, and often trauma, to perform for large groups of people. But we also give them little in the way of support.” She adds that shows dealing “with racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, harassment, or assault (the list goes on and on) can easily bump up against any given artist’s trauma.”

But what does EDI really mean? And how does it work in the arts? When Troilo begins a new project, she starts by defining the terminology. Equality is about ensuring we all have the same things, Troilo says. But the concept of equity recognizes that, as Troilo put it, “We all need different things in order for the opportunity to succeed at the same level. Everyone has a unique, different story which brings them into the room.” When you consider all that, Troilo says, “You reach inclusion, which is everyone feeling like they fully belong and matter in the room.”

When the theatre starts communicating with the director, cast, and crew of a new production, Troilo is included so that everyone knows she’s a resource. She’s also present at the first rehearsal, where she begins with the basics by defining equity, diversity, and inclusion via a presentation. She also helps each group develop community rules and grounding language that feels right for them.

Next, Troilo, the director, and the cast determine if it’s a show where she needs to be present most of the time, like Fairview, or check in only periodically after laying the groundwork, as with English. For Fairview, which uses a birthday party as a lens through which to view racism and surveillance, and then escalates unexpectedly, Troilo was part of the table work, where she helped facilitate discussions on white supremacy culture. On all shows, she’s available to offer creative guidance, advice, and support as issues pop up throughout the process. Additionally, Troilo sends out anonymous surveys if she intuits a challenge brewing, or to check to see if a proposed solution to an issue worked. Finally, at the production’s end, Troilo offers exit interviews so artists can share feedback with the organization.

“I always say the feedback can be anonymous, but some things are so specific that it’s hard,” Troilo said. “Some of the more seasoned actors don’t mind being named,” she explains, but some younger actors are afraid of being the difficult ones, as not being hireable. “I’m working against a deeply ingrained notion for artists that if you complain, you’re a dime a dozen and replaceable,” Troilo said.

A lot happens in between. There’s no one-size-fits-all approach, but her general framework allows casts and crews to get specific about their needs. Troilo doesn’t show up in rehearsals as an expert on any one culture, but she does aim to become an expert on the company’s mission and to offer her EDI skills as needed.

Troilo said she believes she was meant to do this work. In 2020, the pandemic pushed her to reexamine her life and purpose. A Black, biracial mom, actress, and choreographer, she was working full-time to pay the bills and doing theatre to feed her creative side, but the isolation of COVID, George Floyd’s death and the resulting protests, combined with the WSYWAT movement, deeply impacted her, and led to her to ask herself: “What is it I’m doing? What is it I want to do?”

Troilo took a master class in 2021 led by journalist Elaine Welteroth in which she and others were asked to pinpoint their ethos—the driving force behind all they do—and list everything in their lives that is connected to it. For Troilo, her “why” is all about emotional connection. Armed with a fresh perspective, she pruned things out of her life that didn’t align, which led to the end of her full-time job and the birth of her consulting company. She took classes, got certified, and started doing this work more formally.

SpeakEasy was one of Troilo’s first clients. The theatre’s executive director and founder, Paul Daigneault, worked with Troilo on a play in 2019, and during that time, Daigneault said, “I got to know her well. I love how she leads with her heart.”

Later, when Troilo pitched her work to Daigneault—who aims to find organic ways to tell authentic stories, he said, with artists who feel they can bring their full selves to work—he found SpeakEasy and Art & Soul a “mutually agreeable match.”

Daigneault’s company had already committed to their comprehensive SpeakEasy Equity and Anti-Racism Action Plan, in 2020. The organization has updated the plan a few times since then. Still, Daigneault says, “What I’ve been finding is that the goals we set at the beginning were great and very focused, but then, as we sort of jumped in after the pandemic and started producing live theatre again, some of those goals morphed into more specific things that we needed to do.”

Daigneault explained that he wanted to take EDI to the next level and integrate it “into every aspect of our productions. And I thought, if we’re going to take this leap, she’s the first person I want to talk to.”

For Wild Goose Dreams, a play about an unconventional romance between a North Korean defector and a South Korean goose father—a term that refers to a man who works in Korea while his wife and children stay in an English-speaking country—the show’s director, Seonjae Kim, recalled that the company had a ritual of sorts that started with a check-in, which Troilo helped then come up with. Kim said the check-in didn’t have to be physical; it could also be emotional.

“It was really beautiful,” Kim said. “I hadn’t done that in a professional process, and it was nice to find a moment to be human before going to work right away. Also, as a director, especially as a youngish woman of color, often I don’t want to show that I’m sad or that I’m stressed. I kind of want to pretend I have it all together. But I think that ritual encouraged me to practice vulnerability and transparency.”

For the cast of Fairview, vulnerability and transparency were necessary to deal with the show’s difficult themes. This was especially true for Victoria Omoregie, whose character, Keisha, performs a monologue forcing the audience to make a choice. The scene took an emotional toll on the actor, who leaned on her cast members and on tools Troilo provided—such as a decompression room with a yoga mat, blanket, music, and more—to cope. There was also a safe word, “tortilla,” that the cast could use if things got too sticky.

Troilo, the show’s director Pascale Florestal, and SpeakEasy’s Daigneault and Alex Lonati modified the monologue and offered techniques over time to make sure Omoregie and the cast felt comfortable, right up until the end of the show’s run.

Speaking up to change things, asking for help, and participating in difficult conversations can only happen when there’s trust.

“This play required a level of trust between the actors, director, and the audience that I had never quite experienced before,” said Gigi Watson, Omoregie’s co-star.

Watson learned a lot from Troilo’s involvement, and was particularly grateful for the books and fidget toys Troilo provided—gestures she was initially skeptical of, she admitted. Watson also appreciated Troilo’s mention of “how a brave space is one that encourages dialogue and builds on what a safe space is…and providing a framework for safe and meaningful talkbacks.”

Kim, director of Wild Goose Dreams, had other needs for Troilo to meet. Kim wanted to get the details about the setting, the people, and the history right. “I think a [EDI] consultant can be beneficial in navigating those conversations and helping the creative team and cast reach a place where we all feel like we’re in this sweet spot: portraying people’s lived experience authentically onstage.”

Authenticity was also important for Melory Mirashrafi, the director of English. Toossi’s play is about a group of Iranians studying for the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) exam, and examines what embracing a new language means for one’s own. It’s set in Iran, and Mirashrafi wanted the story to be as accurate as possible. Three cultural consultants—one who handled dramaturgy and served on panels, one for in-rehearsal work and design consultation, and one who worked with the marketing team and facilitated post-how discussions—were part of the team.

Mirashrafi said they found freedom in being able to ask for what was needed.

“There’s a wariness about asking for anything and not stepping on anyone’s toes,” they said. After speaking with Troilo, Mirashrafi said they felt their “shoulders relax.”

Said Troilo, “The way I approach the work is [to be] a support system for all. I’m not coming in and lecturing or saying, ‘This is what you need to do.’” Instead, she said, she gets to know the company, from the board to the artists, and internalizes the mission. “I feel it’s important for the EDI mission to match the company’s mission, or else it doesn’t work, and none of it comes from the heart. Otherwise, they’re just doing things to not get in trouble.”

Lasting change is the goal, and those exit interviews Troilo conducts provide an opportunity to achieve it. For instance, Daigneault pointed to constructive feedback the theatre got after English which has changed their practices.

Daigneault noted that one cast member said they had “hoped they would have been asked about dressing room assignments before tech week to figure out how to negotiate that, so we changed our process.” Now, in the welcome email sent before rehearsal begins, a questionnaire asks about dressing room preferences.

Ultimately, Troilo aspires to “eliminate fear from the equation and get us all to a place where we can all feel on board with the mission of the company and the EDI mission that follows.” That way, she said, “It’s embedded into the company and spreads throughout the entire organization.”

Jacquinn Sinclair (she/her) is freelance writer covering the arts, food, and travel. Her work has appeared in multiple publications include WBUR The Artery, Boston Globe, and Boston Art Review.